Product-Led Growth’s Failure

How a Scrappy Utah Software Company Ignored Every Silicon Valley Heuristic and Won Anyway

TL;DR

- This article was informed by exclusive interviews with over a dozen current and former early employees of Qualtrics and SurveyMonkey.

- They all told the same story—Qualtrics should’ve lost but somehow emerged victorious.

- By wielding a 3 pronged strategy of utilizing cheap Utah labor, gutsy product marketing, and aggressive GTM tactics, the company resoundingly beat SurveyMonkey.

- Their story acts as a warning to operators, the things that are popular among Twitter thought leaders are just the flavor of the moment, build the business you want and ignore everyone else.

- There is a reason almost all software companies are built on the back of outbound sales motions. It works.

What if I were to pitch you on a company that had the following attributes:

- Has multiple viral growth loops built into the core product workflow

- Has a 3-year head start over its competition

- Has some of the best technical talent available in California

- Has an active, global user base of millions

- Has deep integrations with Salesforce, Google, Microsoft, Slack, Tableau, Oracle, and basically every other major tech player

- Was entirely subscription-based for many years and has a small services arm started 6 months ago

This looks like a good company! It checks all the boxes that in vogue software investors look for. By having viral growth loops baked into the product, they dramatically decrease their cost to acquire a customer. An active user base fuels a bottoms-up growth method, similar to other software darlings like Slack or Atlassian.

The only problem? This company lost.

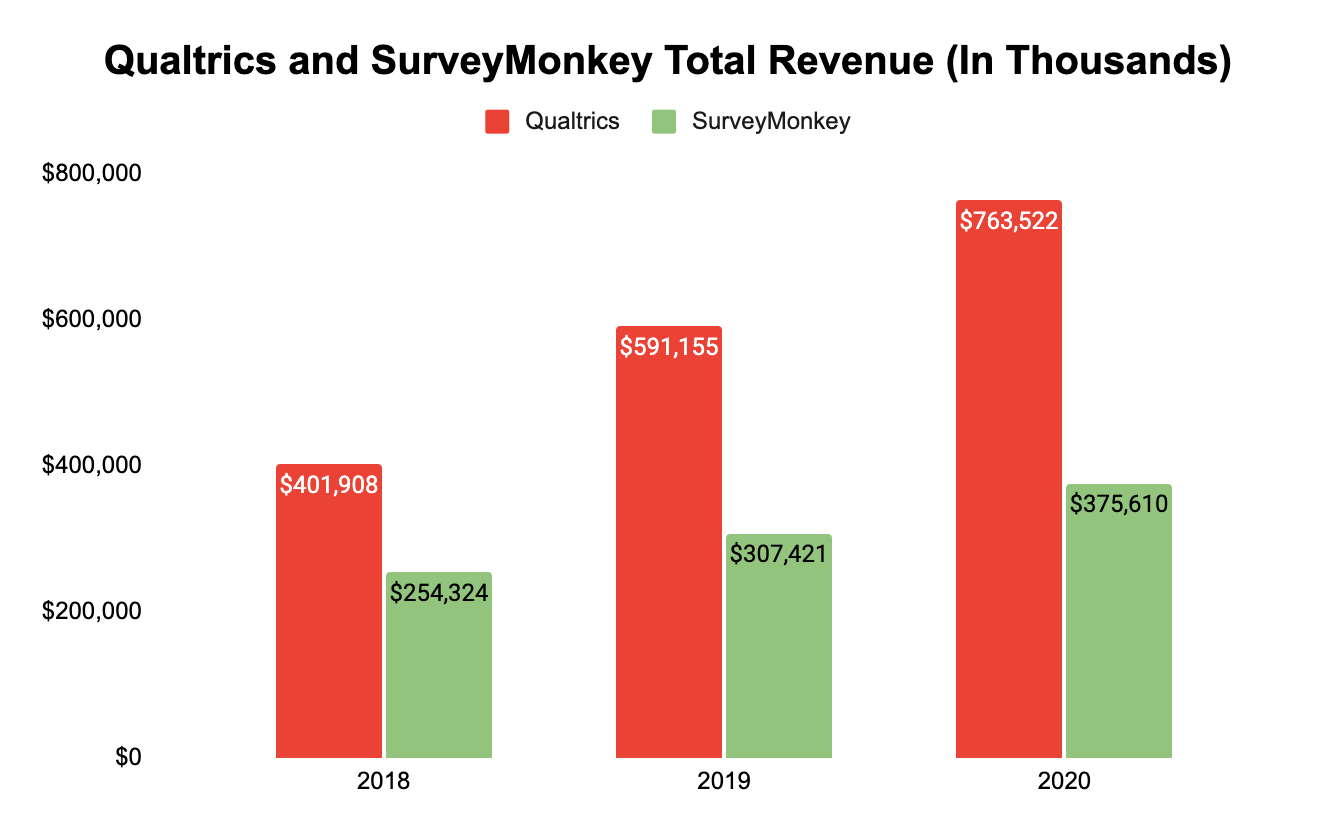

I am describing the runner-up of the survey software market—SurveyMonkey. Despite having everything that modern go-to-market (GTM) theory is built upon (growth loops, channel sales partnerships, and product lead growth) they failed and they failed hard. As of writing, they have a $2.8b dollar valuation in comparison to their top competitors’ $17.6b valuation.

Their foil, their nemesis, was the Provo, Utah-based Qualtrics. It is utilized by the majority of the Fortune 500, has had speakers like Oprah and Michelle Obama at its conferences, and has created its own software category. The one teensy, kinda weird detail is that their product capabilities are nearly identical to Surveymonkey.

How Qualtrics won and why SurveyMonkey lost is a fascinating story that teaches how investors and operators can generate great returns while ignoring what’s hot and instead doing things in a classic way.

A special thanks to my dozen+ sources at both of these companies who made this article possible.

This product is easy to make, so what do we do?

On its surface, surveys are boring. Upon closer inspection, they are still boring. There are essentially 3 things you need to make it work. The first layer is a survey maker tool. (Think of Google forms.) You create the questions, build a list of recipients, and ship it off. The second layer is visualizations. This is where you take the input from the survey and then put it into a chart so an MBA can understand what is going on. The final layer isn’t even technology, it is a services layer! This is where customers will hire professionals to design the survey, source audiences, and give presentations on results.

All of my engineering and product readers are squinting at that last paragraph and thinking, “Well shoot, I can build that.” And you would be right! While building things from scratch is never easy, you are not exactly doing rocket science here. This is not a technically demanding product to build or maintain. So with this in mind, what do you do?

SurveyMonkey decided to stay hyper-focused on the first layer. They built the survey tool, integrated it with every business intelligence or visualization tool on the planet, and then (because investors tend to shy away from COGS-heavy businesses) pretty much ignored the services component. They focused on making their survey tool as easy to use and as lightweight as possible. They hired high-end technical talent, and relentlessly focused on executing easy-to-use features and product-led growth. This playbook was their focus from their founding in 2003 to their IPO in 2018.

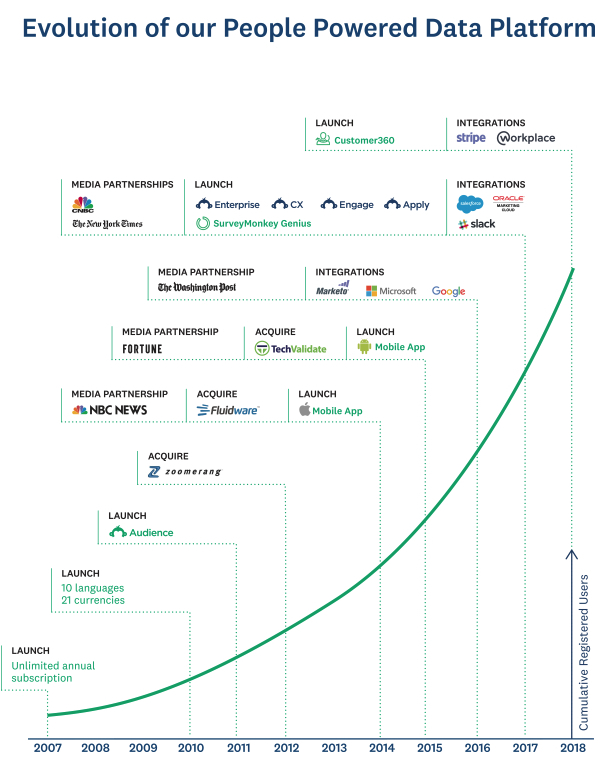

Here’s a chart they made for their S-1 that plots significant events in SurveyMonkey’s history against “Cumulative Registered Users”:

Source their 2018 S1

Qualtrics took the opposite approach. Whether through strategic genius or fumbling luck, they decided to be full-stack. They built their way all the way up the value chain. Survey design? Check. In-house visualization? Check. A large professional services arm that now accounts for roughly ⅓ of revenue? Check. They have it all in-house.

Now I can feel my data analyst and market research readers squinting at that last paragraph and thinking, “I don’t want another visualization tool. My company already has tableau and 6 other options. And also, survey design isn’t really that hard! Why do I need to pay someone for that?” And again these readers, from their perspective, are right. The world does not need more data and analytics tools.

Yet again, we are left asking how on earth did Qualtrics win?

The great art of product marketing

If you control F on the homepage of the two companies you’ll find “Survey” mentioned 47 times on SurveyMonkey’s site. It is in the subheading, in comments, and in the copy. Shoot, it is even in the company’s name! They position themselves as a survey company. If you perform a similar search on Qualtrics’ site, you’ll only find surveys mentioned 4 times and those mentions are buried at the very bottom of the page under popular use cases. Instead, Qualtrics invented something entirely their own, “Experience Management.” What is this? Who cares! Sounds a hell of a lot more valuable than “survey software.”

The core difference between Qualtrics and everyone else is this choice. By doing experience management versus selling software they have shifted from selling tools to selling outcomes. This little idea, of selling impact vs selling technology, is expressed in everything they do. Sales reps (and all Qualtrics employees) are under strict instruction to never make a public-facing statement that uses the word “survey”. By selling experience management, the person they sell to entirely changes. Rather than working through a bottom-up approach, with Product Managers and Market Research Analysts telling their bosses they need this tool, Qualtrics can go directly to the C-Suite. C-Suite doesn’t care at all if they already have visualization tools. They don’t care if surveys are really easy to make. All they care about is the outcome. So when they see content marketing telling them they need to know how their customers are using their product or they want to know how employees are feeling about the return to work they want outcomes. Outcomes can have identical product capabilities as competitors, be harder to use than competitors, and have significantly higher prices. It doesn’t matter. People will pay for it anyway.

Through their sales and account management/customer success teams, Qualtrics is better at integrating into decision-making processes in big organizations. So while SurveyMonkey is just survey software, Qualtrics comes with something akin to consulting: they have salespeople that get the C-Suite to care, they structure the process of setting everything up, they have experience working with companies in similar industries, they give you visualizations, and come up with narratives that explain the bottom line simply.

This is a lot of work. You could do it all yourself, but it requires someone to champion it—aka spend a lot of time getting a bureaucracy to move. Or the CEO could just hire Qualtrics.

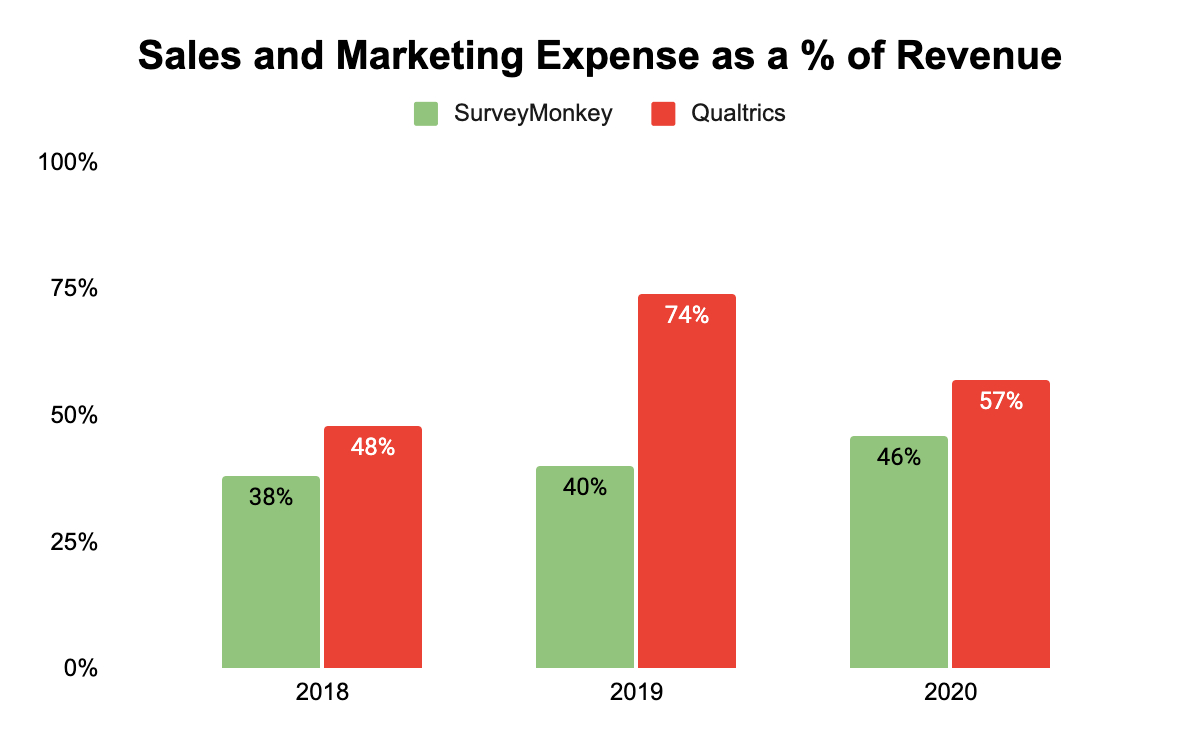

Of course, this strategy came with a cost. By beefing up their appeal to powerful enterprise buyers, Qualtrics had to spend significantly more on sales and marketing than SurveyMonkey, their bottom-up competitor.

Good for SurveyMonkey, right?

Wrong.

Turns out, investing in sales & marketing was critical to winning this market.

This positioning decision also filters down to organizational choices. While SurveyMonkey may spend $300k on a high-quality, well-credentialed Bay Area engineer to build growth loops, Qualtrics can hire 6 entry-level sales reps at $50k a pop in Utah who blanket the country, cold-calling executives, espousing the gospel of insights and experience management. And even once you pump the Utah residents full of Diet Coke and sugary treats, you’ll still have room left over to wine and dine the customers that cold callers find.

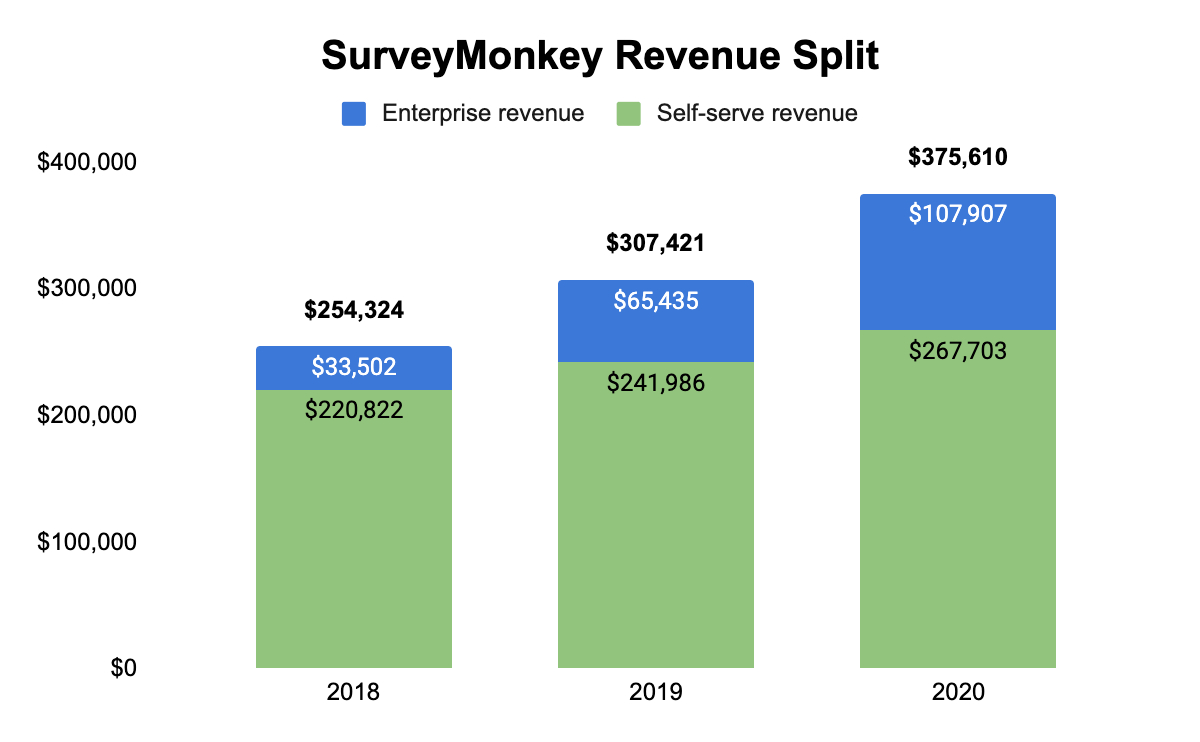

I realize this reads harshly on Qualtrics, but really, it is not meant to be. They won! The choices they made, however strange they may feel, enabled them to build a company that is so scary that when they debuted their financial documents publicly it made SurveyMonkey’s stock price drop 20%. Every other company has been forced to adopt similar business models. SurveyMonkey now has a professional services team (launched ~6 months ago). They now also heavily market survey templates that will give people outcomes. They have made progress with Enterprise Sales Channel Users representing 1% of total user volumes and 40% of total revenue.

But unless they change the name and reposition themselves dramatically, “Survey”Monkey is likely all they’ll ever be.

Qualtrics is perhaps the most stellar example of product marketing to have ever occurred in the history of software. Despite having a more expensive product with similar capabilities to competitors, their positioning empowered their sales teams to win the market and satisfy customers. Once customers are in, they remain in. Qualtrics has a net retention rate of 120% in 2020 with a net retention rate of 125% and 122% as of December 31, 2019 and 2018. In human words, this means that customers net-spend more every year they are with the company. So whether or not an outside observer thinks this is worth it, the company’s customers seem to think so.

In this writer’s opinion, even if SurveyMonkey built identical product features, had an identical sales/marketing org structure, and replicated Qualtrics in every way, they are still likely to lose. After all, they’re “just surveys.” The future of the survey software market is still far from decided, but early indicators have crowned a winner, and that King resides in Provo, Utah, not Silicon Valley.

If this is your first time here, you can continue to get great stories and explainers like what you received today with the button below.

Next week we will be experimenting with a new product so in addition to your usual weekly email, keep an eye out for something special!

Find Out What

Comes Next in Tech.

Start your free trial.

New ideas to help you build the future—in your inbox, every day. Trusted by over 75,000 readers.

SubscribeAlready have an account? Sign in

What's included?

-

Unlimited access to our daily essays by Dan Shipper, Evan Armstrong, and a roster of the best tech writers on the internet

-

Full access to an archive of hundreds of in-depth articles

-

-

Priority access and subscriber-only discounts to courses, events, and more

-

Ad-free experience

-

Access to our Discord community

Comments

Don't have an account? Sign up!

The title of this blog post feels misleading. SurveyMonkey went for a broad product positioning strategy without any focus on use case or segment. Qualtrics focused very directly on universities initially and then large enterprises, building a product with more focus as a result.

That is the defining difference - product led growth is simply how SurveyMonkey gets their product into the building (any building, from the looks of their GTM strategy). I wouldn't attribute the difference in each company's outcome purely to product led growth.

Great read!

I agree that it has nothing to do with the Product-Led Growth strategies SurveyMonkey is implementing in that they are still the leader in the serf-serve space as Qualtrics seems to be more focused on large enterprises, which is almost always more profitable in the B2B space.