Crypto’s Prophet Speaks

A16z’s Chris Dixon hasn’t abandoned the faith with his new book, 'Read Write Own'

Imagine that your belief system became a laughing stock. Twitter grifters made threads about you. Analysts made a name for themselves critiquing your ideas. Politicians used your projects as a punch line. Every day was an exercise in self-doubt, questioning, and suffering.

Most people might decide it was time to take either a nice holiday or a quiet retirement.

This is what happened to Chris Dixon, crypto’s prophet. To his credit, he did not go quietly into the night. Instead, he decided it was time to write a book.

If you are unfamiliar with Dixon, he is the most successful crypto venture capitalist in the world. The man has printed fat stacks of cash for his backers, turning his first $350 million crypto fund into roughly $6 billion. In 2022, when he topped Forbes’s ranking of VCs, his boss at Andreessen Horowitz (a16z), Ben Horowitz, predicted that he would be the "best investor of his generation." The company’s crypto unit, led by Dixon, raised $515 million in 2020, $2.2 billion in 2021, and $4.5 billion in 2022.

On a personal level, I respect his writing and intellectual rigor. His blog was formative for me early in my career; the succinct prose he used to publish on a regular basis made me a better analyst.

All of which is to say that this dude has the juice. He is worth taking seriously.

In a move I admire, Dixon decided to publicly double down on crypto with his new book, Read Write Own: Building the Next Era of the Internet. If there were ever a book and an author by which to cast judgment on the technology’s worth, this would be the one. I have written about crypto, but I’ve never felt comfortable casting an ultimate value judgment. With this book, it was time.

Dixon argues that many of the internet’s problems come down to technical architecture. Because corporations control networks of people and the internet infrastructure they use to connect, corporations accumulate too much power. His thesis is that because blockchains can decentralize some aspects of that architecture, obviating those corporate power centers, the internet will be better for everyone involved.

I would consider myself techno-optimistic. I strongly believe in the necessity of technology to improve our world and have dedicated my life to that belief. It would bring me nothing but the greatest pleasure to announce that crypto solves the internet’s current problems.

I regret to report that both the book’s arguments and crypto’s grand promises fall short of that mark. Yes, corporations are too powerful, and yes, technical architecture is part of the reason why. However, the problems that emerged during the era of crypto scams and scandal in the early 2020s are similarly derived from the blockchain’s technical architecture—just like corporations.

Use cases that almost wholly differentiate on the blockchain’s technical edge, like sending money internationally, make sense, but my belief is that crypto will fall short of Dixon’s lofty ambition for it. His arguments are well reasoned but underweigh several key variables around human psychology and the nature of competition online.

The heart of the issue

The original promise of the internet was to be a free, democratic exchange of ideals. Instead, we got digital monopolies, the collapse of local journalism, and Logan Paul. What happened?

Dixon thinks that corporations are to blame. He views the history of the internet in three distinct phases:

- Read: In the 1990s, anyone could go online and read stuff. The internet “democratized information.” It was the “golden period of innovation and creativity.”

- Read-write: Starting in the mid-2000s, we “democratized publishing. Anyone could write and publish to mass audiences on social networks and other services through posts.”

- Read-write-own: “The read-write-own era, now upon us, is democratizing ownership. Anyone can become a stakeholder in a digital service or network and so gain power, governance rights, and economic upside.” To translate: By using blockchain technology, regular consumers can receive crypto tokens that offer governance rights or economic upside in the services they use, hopefully incentivizing positive behavior.

Dixon’s beef is mostly with the “write” era. In his eyes, big, bad corporations changed everything. Zuckerberg and his ilk “wrenched control away” of cyberspace from the common man. To prove his case, he cites a litany of scary-sounding stats. “The top 1 percent of social networks account for 95 percent of social web traffic.” Or “the top 1 percent of search engines account for 97 percent of search traffic.” Perhaps worst of all, “startups and creative people increasingly depend on networks run by megacorporations like Meta…and Twitter…to find customers, build audiences, and connect with peers.”

I have multiple quibbles with this characterization. A cheap shot I can’t resist making: a16z—Dixon’s employer—is now a major shareholder in Elon Musk’s version of Twitter, and a16z founder Marc Andreessen sits on the board of Meta. It feels funny to complain about the companies that are enriching the firm and man that pays you.

Chippy asides notwithstanding, yes, a select few top companies dominate the internet, but that is because, as I’ve been saying for years, the power law is the only law on the internet.

It is a rule of digital physics, immutable and undeniable. Most of the value always has and always will flow to the top 1 percent.

In 1998—which Dixon saw as the glorious “read” period free of corporate domination—Yahoo had 40 million monthly users when there were only 90 million people online. When Yahoo went public in 1996, there were only 100,000 websites—total. People almost exclusively found them through internet portals like Yahoo. The power law funneled all traffic into aggregators of attention.

Our day is no different, with big tech vacuuming up most traffic. But even on the more niche platforms, the power law still holds. On Twitch, 50 percent of revenue was made by the top 1 percent of streamers in 2021. On Patreon, 70 percent of revenue comes from 3 percent of Patreon accounts. In 2020, the top 10 percent of OnlyFans creators made 73 percent of revenue. The power law stays true regardless of whether the platform is big tech or not.

The reason the power law exists isn’t corporate greed; it is human nature.

And not to go all first-year-grad-student-at-Berkeley here, but the problem of the power law is inherent to the capitalist nature of the internet. Competition for limited eyeballs is the primary driver of the power law. People pay for what they consider the best. If all URLs are competitive, then of course cyberspace devolves into a winner-take-most dynamic for each job to be done for consumers.

The internet is bloody, brutal attention combat, and it doesn’t matter which tech company sits on the throne—the power law is the ultimate ruler. Despite our divergence on the root cause of power laws, however, Dixon and I do agree on how those power laws organize themselves: networks.

The internet has problems

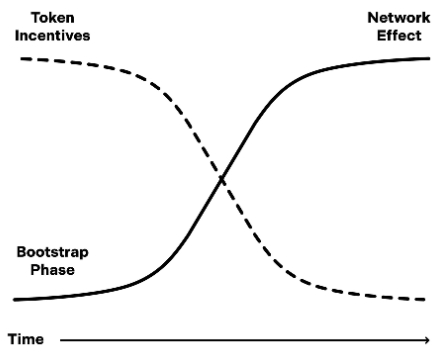

The power law has such gravity partly because of network effects: The more people that join a service, the more valuable it becomes. For many internet companies, these people are a combination of consumers, content creators, and developers. Jump-starting those networks is tougher than you can possibly imagine, but once the flywheel starts turning, each successive user finds more value from the network, and it will grow ever faster (in theory). Each network’s power dynamics are a little different in practice, but that is the general idea.

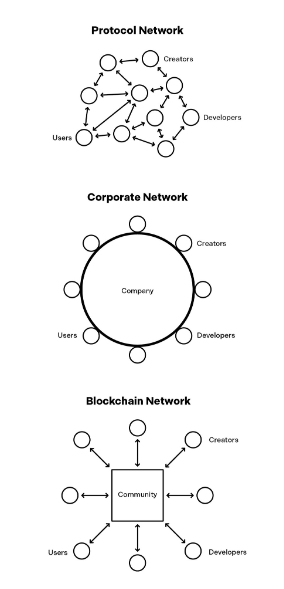

Dixon argues (and I agree with him) that there are three types of digital networks:

- Protocol networks are technical standards that anyone can use and are maintained by a loose federation of nonprofits and global organizations. Dixon has a wonderful definition for these that I’ll happily steal: “Think of protocols as analogous to natural languages, like English or Swahili. They enable computers to communicate with one another. If you change how you speak, there’s a risk other people won’t understand you.” Email is the easiest example of this phenomenon. No one owns it, and everyone builds on top of it.

- Corporate networks are the Facebooks of the world. These are almost always backed by venture capitalists and raise large amounts of money to subsidize users in the beginning. Companies sit in the middle of the network and have unilateral decision-making authority over the rules and operating mandate. All hardware and software is within their dominion.

- Blockchain networks have a decision-making body whose rules are written in immutable code on the blockchain. For the unfamiliar, you can think of a blockchain as a community-run, distributed computer—like a Google Sheet in which everyone can track changes. To gain access to this computer, you get tokens that give you a variety of rights, ranging from economic to governance. Sometimes you earn the tokens by performing tasks, sometimes they are given away by the founding team—it all depends on the project.

Source: Read Write Own.

What we are really talking about with network structures is coordination mechanisms. What is the best way to organize people and resources? How should those people be incentivized?

You can boil Dixon’s network framework incentives down to the following: Protocol networks want their service to stay up. Corporate networks want their company stock to go up. Blockchain networks want their crypto token price to go up. All of the wonder and all of the glory of the internet comes down to those three sentences.

Of course, each of these network methods has its respective downsides.

Protocol networks are a great idea that—according to Dixon—you can’t pull off anymore. The ones that are still successful, like email, were almost all started in the 1980s and ’90s, before any venture capitalists had figured out that you could get stupid rich by owning these networks. In Dixon’s mind, the protocols only ended up winning out because of a power vacuum on the internet. Protocols—like RSS, for my internet readers who remember the good old days of Google Reader—lose the feature battle to corporate networks: Protocols are hard to use and require a decent amount of technical knowledge. By comparison, you could open up a Twitter account with an email and three clicks. Corporate networks can out-build and out-fund protocol networks 99 times out of 100.

Corporate networks have the primary problem of being run by people in San Francisco. If you have opinions or actions that they don’t like, you can get booted off the platform. Because essentially all commerce and information runs through these platforms, there are dire consequences for said booted individual. That isn’t great! And it is a problem no matter your politics. Under Jack Dorsey, right-wingers were always whingeing. Now under Elon, the left is howling. No matter which billionaire asshole CEO you prefer, it still comes down to the fact that moderation of the world’s biggest platforms is run by billionaire assholes.

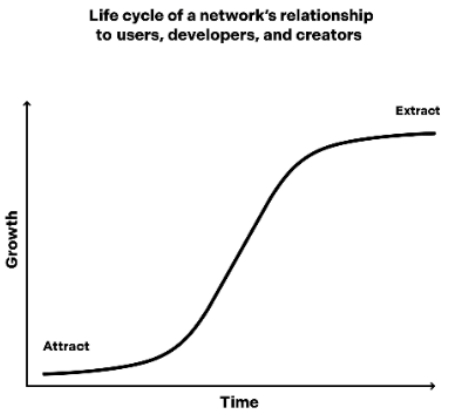

More troubling to me is the take rate that a platform puts on its users. In the beginning, when VC dollars flow like La Croix, platforms will subsidize users to get as big as possible. Eventually, though, they hit their local maxima in users or market and start extracting profits. However, because network effects have already decimated viable alternatives, users don’t have a choice but to pony up. Dixon calls this the attract/extract cycle.

Source: Read. Write. Own. Dixon used another version of this graphic in a 2018 blog post. These ideas have been circulating for longer than the Chiefs have been winning Super Bowls. For comparison, the "Attention Is All You Need” paper that is the foundation of the current AI boom was published around the same time.

To Dixon, the attract/extract cycle means that “the interests of the company and network participants are simply misaligned, resulting in a worse experience for the user.” This is a little hand-wavy. Yes, the experience is worse, but only in comparison with the subsidized experience. If a consumer sticks around, it is because they still find the experience net beneficial.

I’m not saying that the attract/extract cycle isn’t real. You’ll notice it yourself in how Google and Amazon deliver way more ads than usable results these days. Developers locked in a battle with Apple over its high fees are also vigorously nodding their heads. Still, these burdens are only onerous to the point where extraction doesn’t cause excess churn.

If a corporate network extracts too much, users will swap it for something else. Ad loads are an easy example to understand. Despite Google having more ads than Elon Musk has kids, the network continues to do well because users' marginal utility is still positive. If Google shows too many ads, users will eventually find their marginal utility turn negative, resulting in them churning for other search engines. This is happening right now! AI services like Perplexity and Bing are trying to steal market share from Google with search results that have fewer ads.

Every illustration

Dixon makes the point that perhaps the greatest downside of the attract/extract cycle is the damper it places on startups. We will never know the cool apps that would’ve been built if Apple didn’t extract 30 percent from its developers, or what unhinged science could’ve unfolded on Twitter if the company didn’t have a moderation team. If we continue on the path we are on, corporate networks will “crowd out innovation and productivity. Left unchecked, this will lead to economic stasis, homogeneity, unproductivity, and inequality.” To me, it feels a little grandiose to blame App Store fees for social inequality (racism comes to mind, for one alternative explanation). The iOS operating system is a genuine marvel for which Apple deserves compensation.

This argument is a great example of my frustration with Dixon’s book. He’ll make intelligent, accurate assessments of the world: Attract/extract is a real problem. Power laws, driven by network effects, do mean that corporate networks grow incredibly powerful in cyberspace. But then, on the cusp of making a genuinely novel insight, his prose devolves into either 1) populist anti-big tech rabble-rousing or 2) arguments for the blockchain that would’ve been convincing…in 2018.

It's like watching a chef spend six hours preparing the world’s most delectable chocolate cake, smeared with delicately fluffy icing and topped with sugar-coated cherries, only to watch them use stale Halloween candy as a final garnish. It’s so close to greatness, but the final taste is just a little off.

Back to Dixon’s argument, which, as a reminder, is: Networks are a coordination mechanism for groups of people. Each method has its relative merits and weaknesses. Protocols are decentralized but weak. Corporations are centralized but strong. He proposes that blockchain networks—the third option—can be the best of both worlds.

Blockchain, schmuckchain

Chris Dixon strides across the stage in jeans and a black turtleneck. An adoring audience of tech journalists awaits with bated breath for his latest product announcement. A logo of an egg with a bite taken out of it—modeled after Marc Andreessen’s head—flashes on a screen behind him.

“Today, a16z is pleased to announce three revolutionary new products. The first one is a new way to incentivize communities. The second, a way to show digital ownership. And the third is a breakthrough, globally distributed digital computer.

A new way to incentivize community.

A new way to show digital ownership.

A new, globally distributed computer.

Community.

Ownership.

Are you getting it? These aren’t three separate products. They are one product. We call it the blockchain network. Today a16z is going to reinvent the internet.”

Limited partner money drops from the ceiling as party favors. The crowd roars.

This scenario is obviously farcical (and a throwback to Steve Jobs’s introduction of the iPhone, in the single greatest product keynote of all time), but it is helpful to think about the blockchain networks (BN) as multiple products in one.

The blockchain is that Google Sheet I mentioned earlier. It is a special type of database where anyone can see what is stored on it. All changes to it are publicly trackable. The hardware on which the database’s code is crunched is digitally distributed on token holders’ devices. To take down a blockchain, thousands, or tens of thousands, of computers all over the world would have to go kaput. The code operating the blockchain is encoded from the get-go, and in most cases, it can’t be changed because there is no central owner. It is so powerful that an axiom in crypto is that “code is law.” (Remember this point—it will be crucial later.)

Tokens are digital assets that sit on top of the blockchain. If stocks, property rights, money, and HTML had a particularly sweaty orgy, a token is what would pop out nine months later. Think of them as digital Pokemon cards. Each comes with a combination of powers to do stuff and rights they are guaranteed. Individuals’ purchase or use of tokens funds the computing resources required to run the blockchain.

When you combine the qualities of blockchains and tokens, Dixon argues that you get a superior network that has the best characteristics of both protocols and corporate networks. Because a blockchain isn’t owned by a centralized party and its operating mandate is encoded from its formation, it closely mirrors a protocol. Since the code can’t be changed, developers and creators can build products on top of this technical infrastructure with confidence.

The killer competitive advantage for corporate networks has always been capital. They can raise a lot of money to fund feature development and purchase market share through ads or user subsidies. For a BN, tokens act as an alternative funding mechanism to traditional venture capital. A token’s function varies widely depending on the blockchain on which it is based, but in general, tokens function as equity in the blockchain, an asset that has some sort of use on the blockchain, or some combination thereof. But crucially, you can just invent them! Tokens don’t cost money to make. They’re essentially digital IOUs.

The result is that founders can kickstart a network by distributing tokens for free with the promise of future riches and utility. Dixon visualizes it like this:

Source: Read Write Own.

This is a compelling vision of the internet of the future. It offers a legitimate path to disrupting corporate networks and giving more power back to the people.

It’s also from a blog post in 2017.

Dixon is, once again, playing the hits that kickstarted the speculative mania of the 2020s. I remember reading this post when he first published it and thinking that it contained genuinely novel ideas that offered a viable strategy to topple the internet giants. It is rare for a tech analyst to write one essay that breaks through. Dixon had multiple from 2016-2020, most of them about crypto—and most of them constitute the arguments of this book.

Many people read and acted on his words.

Over the last four years, venture capitalists have poured roughly $90 billion into crypto projects. When you add in the seven years since Dixon proposed that crypto tokens could bootstrap networks, plus enough capital to replicate the GDP of Bulgaria, you would think that blockchain networks would be disrupting corporate networks left and right.

That…is not what happened.

Read Write Meh

What actually happened was unhinged. If, for the purposes of mental health and sanity, you have blocked out your memories of 2020, God bless you and stay free.

Otherwise, you may remember people spending $1.3 million on a picture of a rock. Many, many average people lost their life savings after being scammed by one crypto project or another. There was crime and gambling and fraud. It was a wild time. To his credit, Dixon has publicly stated his distaste for the speculation that occurred in this period. He correctly views this era as a net negative for the blockchain sector.

When I started the book, my biggest question was how he would address this problem. Unfortunately, his treatment of this era is intellectually limp. In 289 pages, he devotes only one chapter to the topic of speculation. Within the chapter, he writes only two pages about this era of fraud. The rest of the chapter is devoted to the regulation that is being written in response to the excess of the 2020s.

His explanation for the speculative mania of this time is that “two distinct cultures are interested in blockchains. The first sees blockchains as a way to build new networks…The other culture is mainly interested in speculation and money-making. Those of this mindset see blockchains solely as a way to create new tokens for trading. I call this culture the casino because, at its core, it’s really just about gambling.”

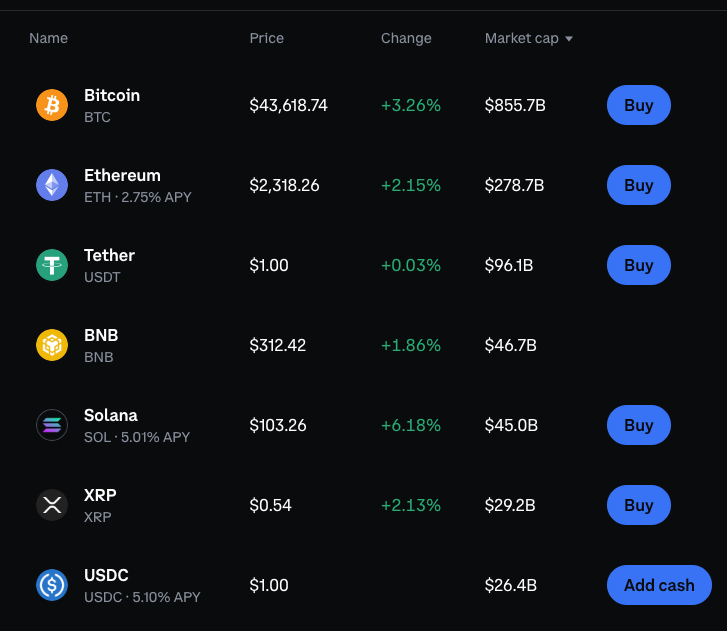

And that’s it! He never goes any deeper into the root of the problem. So allow me to help him out with a single screenshot. Ironically, it comes from his own portfolio company, Coinbase.

Source: Screenshot of the Coinbase trading platform.

Can you spot the problem? Look at the percentage change column in green. While each token has a unique combination of capabilities and incentives, they all get compared on one single metric: the internal rate of return. This puts all blockchain projects, as I proposed in May of 2022, on a similar plane of competition. Said more simply, because consumers compare each token based on how much money it makes, all the other stuff will always be marginally relevant.

Imagine if one McDonald’s stock got you one free large Diet Coke. This is nice! But you’re probably going to buy the stock to, well, buy the stock, regardless of associated snacking privileges. This very human impulse to make money will abstract away all the other stuff a token can do because all of them are tradable on a marketplace like Coinbase.

If, as Dixon theorizes, blockchain networks need tokens to compete with corporate networks, from the very moment of each blockchain’s inception the comparative financial rewards of the project are being weighed relative to other investment opportunities. If the early adopters of the product are more interested in the other capabilities of the blockchain beyond making money—such as decentralization or being digitally native—why give them financial upside in the first place? Just build a product and sell it based on the job to be done like a normal tech company.

He gets so, so close to drawing this conclusion. About halfway through the book he writes, “Tokens are not magic beans. They are assets used to power virtual economies, and they can be valued using traditional financial methods.” Yes! Exactly! And if they can be valued on financial metrics, they will be.

It is reasonable to expect people investing their time, money, and resources to do a comparative analysis to seek out the highest yield. It is foolish to suggest that this is a cultural problem. True believers in the blockchain will participate regardless of financial incentives. Anyone else can and should expect financial upside.

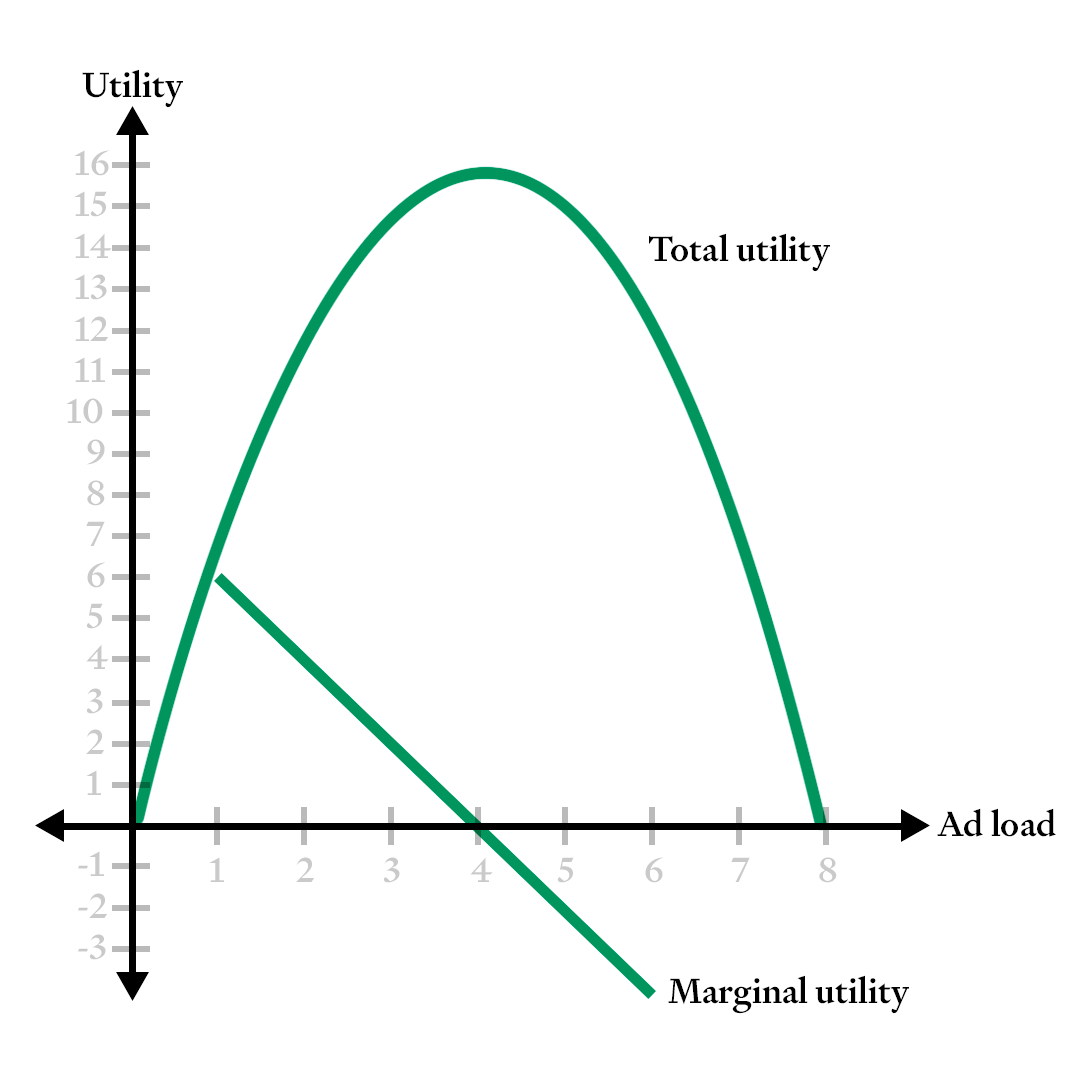

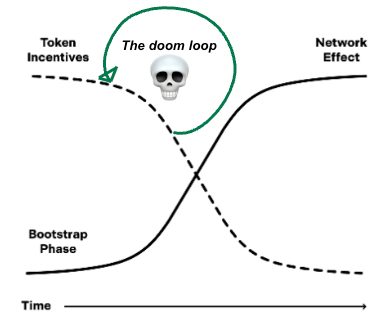

Ironically, the very nature of the blockchain creates its own attract/extract cycle. I call it the attract/extract doom loop. A blockchain attracts new users to its network by offering financial rewards, with early users extracting the maximum amount of yield possible. As soon as the yield starts to slip below acceptable levels, users will loop back around by selling their position and moving on to another crypto asset that gives them the same amount of return they received previously. This dynamic prevents almost every single crypto project from crossing the utility rubicon to no longer needing to offer financial reward.

Every illustration/Read Write Own.

The attract/extract doom loop leaves blockchains with only three viable options:

- Utility only: They offer no financial incentives and compete on utility unique to the product the blockchain is offering. Many of the more successful projects have use cases in decentralized finance or remittance payments. Both of these realms have major problems for end users that are being uniquely solved by blockchain technology.

- Thread the needle with tokenomics: In theory, a perfectly designed utility curve could allow someone to design the incentives such that each decrease in yield is matched by its equivalent in utility. To pull this off, you simultaneously have to exactly forecast a multi-year economic scenario for a new startup and perfectly understand the utility users will derive from the network. Unless you are economics Jesus, this math is likely impossible.

- Extreme lock-in: Token backers could be restricted from selling their tokens for many years. After all, this is how startups obviate the volatility of their equity prices in the early years, so you could have similar five- to 10-year lockups for crypto projects.

Dixon has mostly discussed the third option in his podcast tour for the book.

Do you see the irony? In his attempt to destroy corporate network lock-in for users, he suggests that blockchain founders lock in early users with financial penalties. Maybe the final outcome of a blockchain network is superior enough to justify such draconian terms, but in a world where dollars are scarce, most people are going to pick the BNs offering comparable products and no liquidity restrictions. If there are five social media blockchain projects, early adopters are always going to prefer the one that allows them easy liquidity.

The casino nature of crypto is not a cultural phenomenon—it is fundamental to the very technology itself. However, the financial nature of crypto goes far beyond simple yield comparisons. Dixon expects it to protect against illicit action, too.

Crypto as failed state

One of Dixon’s favorite analogies is that crypto is like a digital, democratic city. The code governing the blockchain acts as the law, and the network is run by the people. It’s American libertarianism delivered via fiber optic cables, baby.

This is funny, because, one, America isn’t a democracy. We’re a federal republic powered by representative democracy. We don’t actually put power in the hands of the community. Our laws are created by centralized decision makers who we entrust with power, which is the opposite of what Dixon purports.

Second, this digital city is neutered in its capabilities. Dixon argues that “even if some users are dishonest and would rather game a blockchain for profit, the system keeps everyone honest. This is the genius of the system: a set of incentive structures that makes it self-policing. Through well-calibrated economic rewards, blockchains get users to keep one another in check.”

A normal government has two tools to encourage behavior: money and guns. As far as I am aware, there is not yet a crypto token with the firing power of a Beretta, so blockchains are only able to incentivize behavior with financial tools. Therefore, Crypto Town has no police and can only stop crime with strategically placed ATMs. When you add the attract/extract doom loop to the mix, of course the result is financial chaos.

The crypto “democratic city” analogy has further weaknesses that highlight the problems inherent in crypto’s very nature. “Code is law” is a terrible form of governance. If we had designed our laws up such that they could never be changed in the United States, one of the greatest governments ever designed, then Black people would still only politically count for three-fifths a person. Centralizing power into decision-makers’ hands allows for updates to be made based on market conditions.

For blockchain networks to adapt to competitive pressure, they have to have a decisive, courageous decision-making apparatus. Networks require a form of protection and care that is exceptionally challenging in a community governance model. To beat Facebook or Wells Fargo, you probably need an asshole-in-chief. In blockchain networks, thousands of assholes are running the show.

If everyone’s in charge, nobody is.

What crypto can ultimately deliver

Finally, I found it strange that Dixon was so reticent to be specific with his claims about the future. After his chapter about fraud (which he calls “The Computer Versus the Casino”), he devotes the few remaining pages of the book to hypothesizing the future of the blockchain. His topics range from social media to AI and financial services. To his credit, he offers up some hypotheses on how blockchain could change these markets that are reasonable if you believe his thesis.

What is weird is that his team manages over $7 billion, deploying that capital into more than 103 companies, yet he mentions fewer than 10 in the book. This is a chance for him to talk up his own book in his literal book. You’ve deployed billions of dollars! Tell us why, and in what!

There are almost certainly rules about what he can disclose as an investment manager, but at the very least, every one of his points should have had an in-depth case study from his portfolio. Bizarrely, of the few case studies he did offer, two highlight the very criticism that I’ve been writing about:

- Helium: A blockchain network that competes with traditional cellular networks. Consumers could buy cellular routers, set them up at home, and earn tokens when people made calls via their router. Good idea! And in a sense, it worked. Many people bought these routers. In a more fundamental—no, scammy—way, it very much did not work. The founders enriched themselves by capturing nearly all of the tokens, and they allegedly lied about who their customers were. Many of the people who bought routers for hundreds of dollars now only make pennies. While tokens funded the network’s early growth, the utility curve was totally miscalculated, and large demand for the network has yet to appear.

- OpenSea: Think of this company as eBay for NFTs. One of Dixon’s main arguments is that blockchain networks have much lower take rates because all competition is built on the same technical architecture. In that sense, he is right. OpenSea was dominant until a competitor called Blur set much lower take rates and started taking market share. OpenSea lowered its rate, too. But what Dixon doesn’t mention is that as part of this take-rate decrease, the company removed the royalty fee that it paid the original artist behind the NFT, which was a core promise of NFT art. This is a clear failure of Dixon’s assurance that blockchains are better for creators. Dixon knows this, and he knows this story: He sits on OpenSea’s board.

I may be a little nitpicky with these examples, but this is supposed to be the book—the chosen one to convince the masses that crypto was the future. But when I examine the arguments, I find them lacking. The examples are directionally accurate, but the details omitted are disconcerting. Every time I dug deep, I found myself bewildered that Dixon hadn’t updated his thinking.

The book also reads like some part of Dixon himself lacks confidence. I found only one instance where he made a specific claim about timelines: He said that blockchain infrastructure is now good enough that developers can focus on end-user experiences, and this dynamic will “act as a force multiplier over the next few years.” Otherwise, he mostly hedges, arguing that we are the midst of another 10- to 15-year computing platform shift. If you believe enough in this sector to have bet your career and $7 billion on it, I would hope that you could say with some confidence when the internet will be fixed.

Dixon’s book is a convincing argument for crypto—just not in the way he thinks. I finished it believing that blockchains can solve niche use cases that rely on the technology’s properties. I was equally convinced that crypto’s promise has been greatly inflated. It would be wonderful if I was wrong and Dixon’s vision of a democratic, cheaper internet comes to pass, but in the meantime, I’m focusing my attention elsewhere. It could be AI, a platform shift like Apple's Vision Pro, or something else entirely, but my hunch is that our savior doesn’t reside on the blockchain.

Find Out What

Comes Next in Tech.

Start your free trial.

New ideas to help you build the future—in your inbox, every day. Trusted by over 75,000 readers.

SubscribeAlready have an account? Sign in

What's included?

-

Unlimited access to our daily essays by Dan Shipper, Evan Armstrong, and a roster of the best tech writers on the internet

-

Full access to an archive of hundreds of in-depth articles

-

-

Priority access and subscriber-only discounts to courses, events, and more

-

Ad-free experience

-

Access to our Discord community

Comments

Don't have an account? Sign up!

Excellent post. Per your last paragraph, what do you think about blockchain as an infrastructure for an AI based economy, ie a ledger for AI to transact with AI.

@Mark_5418 i think it could work? Honestly, the devil is in the details—attribution, what blockchain, etc—that I don't think anyone has sorted out yet. The theory could be right? Vaguely similar to my feelings on crypto before writing this review. Good idea, details are iffy.

Loved this post! The arguments were very strong, nuanced, and well researched. They were written with great clarity in thought and simplicity in style. I enjoyed your writing style a lot and was taking notes — will be back for more

@sajjad585 Thank you! I appreciate that :)

So glad you decided to take this on and provide the benefit of your experience, wisdom, and well-calibrated bullshit sniffer. Your article proves again why Every in on my desktop. I don't have to care about crypto and I don't. I am curious. You write to the curious. You provide worldview information and being well-informed makes for rich and deep conversations. And better questions.

@Georgia@Communicators.com Thanks Georgia! appreciate that

Really good write-up! It's hard to read a book by him as anything other than looking to prop up his investments but I think you approached it very fairly.

I'm failing to find the clip but there was one with Chamath and some other crypto investors basically describing how they would fund tokens and then exit early at the peak. It was so damning of the entire VC industries treatment of crypto as purely a speculative investment vehicle while they try to say otherwise.

I say all this as someone who was amazed by Ethereum and its promises for computing years ago. I still find it all technically very impressive, but I am not convinced it really offers enough to go spend my time trying to build with it.

Found it - https://twitter.com/SilvermanJacob/status/1595059806200643589

Well balanced article. Agree on risks of hard coded “laws “ - we know the problems this causes with literal religious zealots. Also the need for an effective organizational architecture to have both carrot (incentives) and stick (punishment).I am excited by the transparency blockchain record keeping brings, plus the joyful self adaptation of these huge open-sourced systems

What a rollicking great read!

‘ If everyone’s in charge, nobody is.’

I'm thinking chaos & Blockchain & patterns like a roller coaster with no track.

Driven largely by emotion and fantasy.

Blockchain is pushing change which is a good thing.

Almost bought the book but now I don't feel that's necessary given this clear summary and incisive analysis. My Every subscription is paying for itself! Pls keep it up

"I may be a little bit nit-picky with these examples" No, the specificity and attention to detail is what makes this article great. I think Dixon is someone who got in early, made a lot of money, and now he is "the guy" to go to about crypto. He succeeded in this space, he is still making his living off of it, winning is great, but failing teaches. He hasn't failed, his job is secure, he is managing billions of dollars, so he holds firm to the ideas that ignited his passion for the space in the first place. He is to crypto what Ninja is to streaming: the man who got in at the right time, became the face of the movement/ idea, and made the most money/ had the most success that anyone ever will. More than anything, I just have to believe that anyone who is so sure in such extreme, "all-in" views is wrong in some way, because everything is nuanced, there is no magic wand to wave that will make everything perfect.

Hello:

I just listened to an interesting podcast with Mr Dixon on the a16z network and he stated that he would like to respond to comments, pro or con. I think it would be interesting to learn from the two of you chatting???