“The value chain” is the DNA of business

An introduction to one of Michael Porter’s most enduring frameworks

January 8, 2020

When a biologist looks at a dog, they don’t just see a friendly bundle of fur, like we do. Instead, they see a complex web of causal relationships and structures. It’s not just a creature—it’s a puzzle.

To solve it, they use fundamental frameworks like DNA, organs, and cell division. And they’ve gotten incredibly good at it. For example, we can now engineer viruses that, when injected into a cell, can edit precise bits of a genome in order to cure diseases.

That’s amazing.

Businesspeople, in comparison, know very little. To fix that, we need a better shared understanding of fundamental frameworks.

Over the past few weeks we’ve explored two such frameworks:

- Markets as Ecosystems - the idea that competition works like an evolutionary ecosystem

- Trade-offs - the idea that strategies are shaped by trade-offs

Today, we’re going to explore a third. Perhaps the most fundamental business framework of them all: the value chain.

Mapping the value chain

When I first joined Gimlet Media as head of product in 2017, I wanted to take a bit of time to understand the larger podcast ecosystem we existed within.

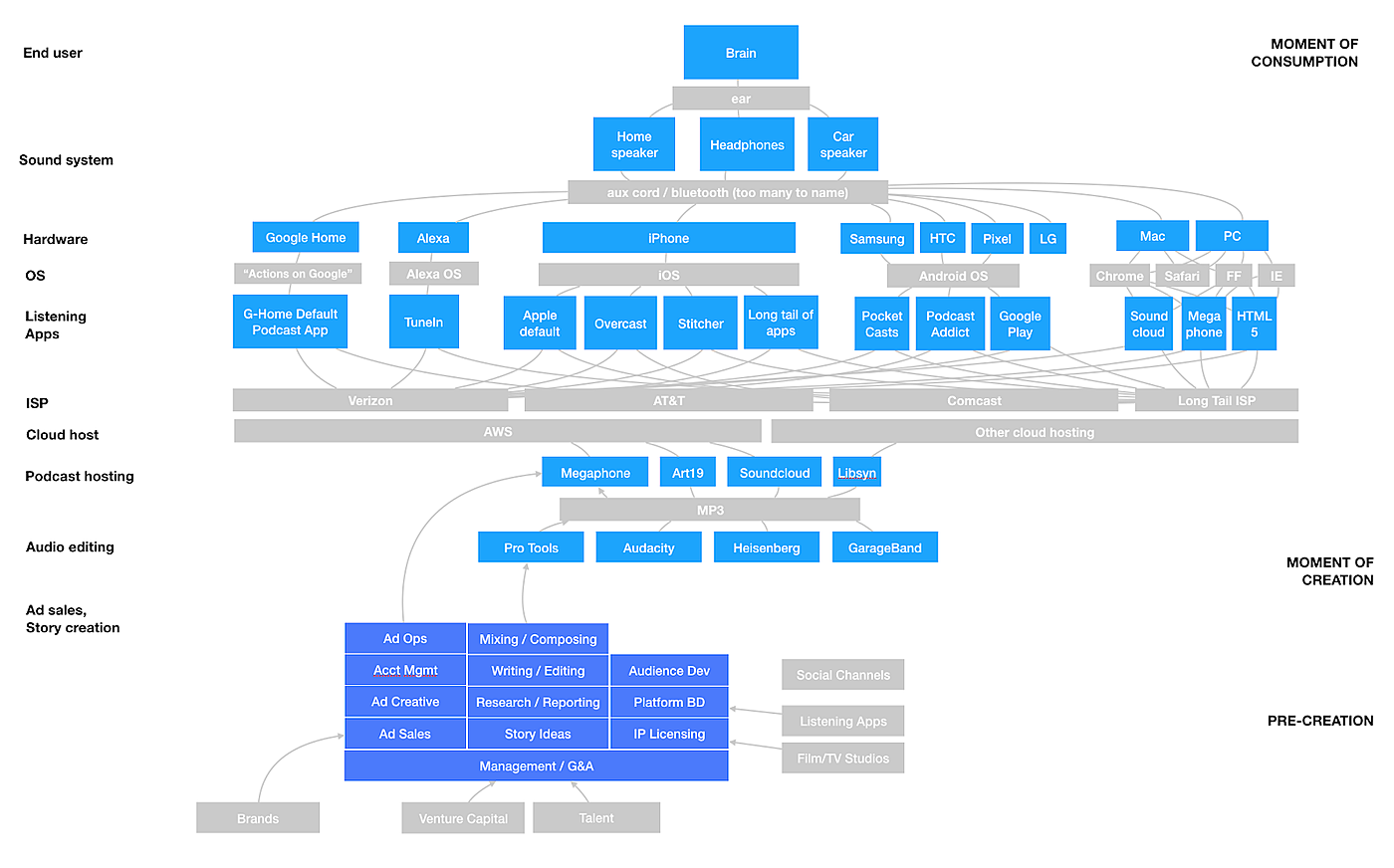

So I made a map:

The idea was to force myself to think through all the layers of the stack our business depended on. It wasn’t something I ever showed colleagues, or even, honestly, revisited very often. But the process of making it was what mattered.

Each box in the value chain map represents a specific activity. At the bottom, I put the foundational activities that happen earliest, like “raising capital,” and “recruiting journalists.” The way we performed those activities influenced what happened at the higher levels, such as “gathering story ideas” and “editing audio.”

It’s one big, messy, interdependent chain of activities: the stuff at the top (e.g. the physics of human ears, and speakers) influences the stuff at the bottom (e.g. mastering audio).

You can use it in all sorts of ways:

Predict new entrants

When I sat down to plot it out, I was forced to consider all sorts of questions that may never have occurred to me otherwise. For example, what’s the market share of Pro Tools in podcasting? Why do we use it? Turns out, Pro Tools creates a lot of headaches for podcasters, which created room for new entrants like Descript and Anchor.

Develop new products

There were big opportunities hiding in the map. When I listed out all the different hardware and operating systems people use to listen to podcasts, it helped me notice that Alexa and Google Home were underdeveloped but growing—a potential opportunity.

Of course, Gimlet’s founders were already well aware of this and had a project in the works. But when I took the projects over, the map gave me a lot more strategic clarity about why they were important, and how to best leverage Gimlet’s skills to make them work.

That year, we partnered with Amazon and P&G to build an Alexa skill called “Chompers.” It’s a two-minute show that entertains kids while they brush their teeth. Parents love it, because it is, apparently, really hard to get kids to brush their teeth for the recommended two minutes, so it was a hit.

Spot existential risks

The map also helped me spot potential risks to Gimlet’s business. For example, the podcasting world mostly runs on podcast apps, and podcast apps mostly run on iOS and Android. So those two operating systems—and, more specifically, the companies that own them—have the potential to exert a lot of control over the ecosystem. So far Apple and Google have been fairly hands-off, but that could change. (Just ask Spotify.)

Clarify your understanding of reality

But most importantly, the map helps you construct a mental model of how markets actually work. When people write refer to “the podcasting industry,” it’s a pretty fuzzy concept. But when you draw out how, physically, value flows from creator to consumer, it becomes a lot clearer.

What is a “value chain” ?

I got the idea to make this map after I read Michael Porter’s incredible 1985 book, Competitive Advantage.

Back then, most businesses were more focused on operational efficiency than strategy. The assumption was that every company in an industry would pretty much do the same thing, but some businesses, due to their scale or experience, would be able to do it faster, cheaper, or better than competitors. So it was a rush to scale with undifferentiated products.

Porter’s big idea was that selecting unique activities—i.e. having a strategy—was a better route to sustainable profitability over the long run. To explain why, and to give managers a framework to think these problems through, he invented “the value chain.”

Here’s how Porter explained it in the introduction to Competitive Advantage:

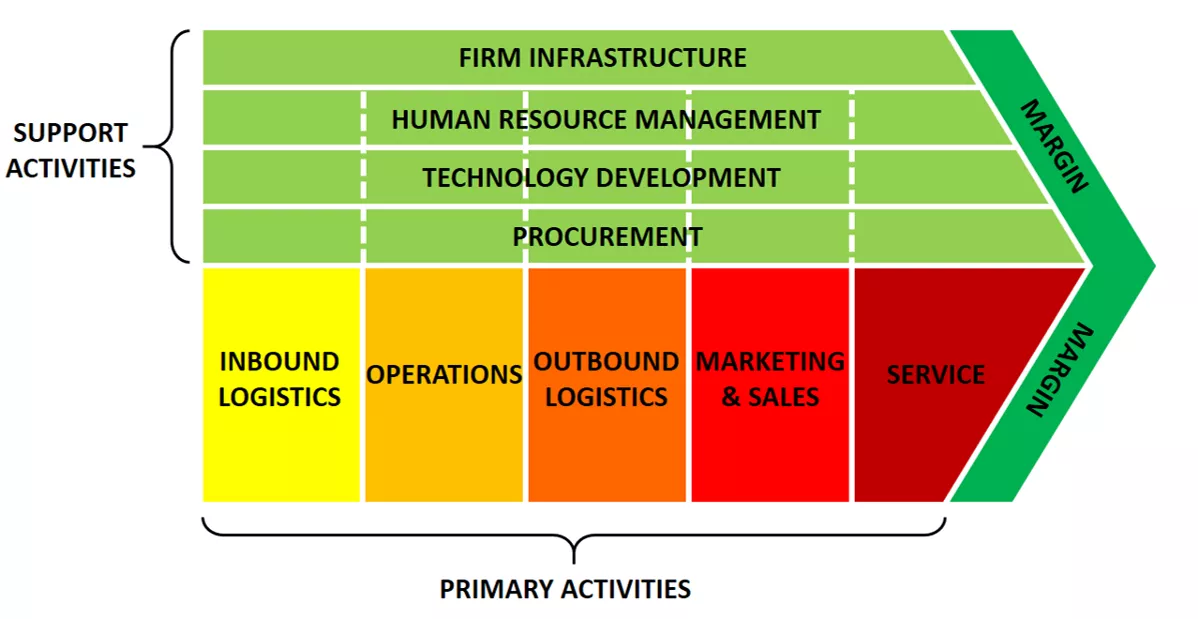

“At [this] book’s core is an activity-based theory of the firm. To compete in any industry, companies must perform a wide array of discrete activities such as processing orders, calling on customers, assembling products, and training employees. Activities, narrower than traditional functions such as marketing or R&D, are what generate cost and create value for buyers; they are the basic units of competitive advantage.”

His original diagram is still great:

The idea is that each of these boxes is a generic category of activity, and you’d fill it in with the specific activities that your company actually does. It’s like a worksheet, of sorts.

“The essence of strategy is in the activities,” he said. Choosing a clear strategy, and tailoring your activities ruthlessly to fit that strategy, is what creates superior performance.

What counts as an “activity”?

When you start making a map of your business or industry, the first thing you’ll notice is how hard it is to decide what counts as an “activity.”

For instance, in my map of the podcast ecosystem above, I break out the process of creating a podcast episode into separate boxes for “research / reporting” and “writing / editing,” but I lump all of Apple’s Podcasts app into one big box. In reality, of course, there are many functions it performs that could each have their own box.

“Activity” turns out to be a slippery concept. It’s fractal. You can zoom in and out at will.

My best advice is to not worry too much about whether you’re properly zoomed, and to trust your intuition. You can always make it more or less granular later. The important thing is to think everything through.

Porter’s advice is to group together activities that have similar economics and relevance to the value you create for buyers. For instance, if you have three different types of QA processes but they’re all geared toward finding defects, and they all have very similar cost structures, then you can probably safely group it into one larger bucket for “QA.”

How do activities contribute to competitive advantage?

The process of mapping out your business’s activities increases the chances that you’ll notice places where you could invest more (to increase differentiation) or less (to reduce cost). But these changes are only a good idea if they reinforce the overall position you’re trying to establish.

For example, if you mapped out Costco’s chain of activities, you’d notice they do almost nothing to decorate their stores. You might conclude that they could attract more shoppers by sprucing the place up a bit. And this might be a great idea in the context of some other strategy (like, for example, Whole Foods). But it’d be a terrible idea for Costco.

That’s an obvious example, but when you go through your own value chain you’re likely to notice much more subtle and powerful ideas. It won’t always be obvious whether they fit your strategy.

Porter calls the process of adapting your value chain to your strategy “tailoring.” It takes years to kick off, and never really ends. Startups are born into the world with awkwardly fitting value chains, and gradually discover how to tailor them, based on the demands of the market and the trade-offs they uncover.

This is why, even though high-performing businesses are constantly improving and changing, it’s so important to stick with a consistent strategy for long periods of time.

“Linkages” and “Fits”

The reason Porter called it a value “chain” is because each activity affects—is affected by—all the others.

For example, with Gimlet:

- The way you raise capital influences the way you decide what podcasts to create

- The podcasts you create influences the kind of journalists you hire

- The journalists you hire influences the kind of stories you produce

- The distribution channel (podcast apps) influences the business model (ads)

You’re looking for a system where all the activities work together and fit each other. A great framework for this that’s most relevant to startups is Brian Balfour’s “four fits.” Basically, the idea is that your product, market, business model, and growth channel all need to work together to support each other.

This is essentially an extension of Porter’s thinking.

“Loops”

So far, we’ve only covered value chains as linear phenomena, but every large business is the result of an exponential function—a positive feedback loop.

In reality, the best value chains loop back upon themselves. That means the result of going through one “cycle” is the next cycle happens in an even better way. Some people call this a “flywheel” or an “accumulating advantage.”

This post is already too long, so I’m not going to dive all the way in. Instead, I want to give this idea its own post, later on.

In the meantime, you can read this post by Kevin Kwok, Brian Balfour, Andrew Chen, and Casey Winters. You can also check out Turning the Flywheel, a nice short book by Jim Collins (author of Good to Great).

Fin

That’s it for today–thanks for reading!

If you liked this post, please train my “neural net” and click the purple “Like & Comment” button below.

(This is no vanity exercise—the main purpose it serves it to create a feedback loop for me, so I can make Divinations better for you!)

As always, would love to hear all your comments and questions below. I’ll be hanging out and responding in a timely manner. There were some really interesting ones on the last post, so thank you!

See you tomorrow! (We’ve got an interview coming up with Sahil Lavingia, Founder of Gumroad, that I think you’ll love.)

Find Out What

Comes Next in Tech.

Start your free trial.

New ideas to help you build the future—in your inbox, every day. Trusted by over 75,000 readers.

SubscribeAlready have an account? Sign in

What's included?

-

Unlimited access to our daily essays by Dan Shipper, Evan Armstrong, and a roster of the best tech writers on the internet

-

Full access to an archive of hundreds of in-depth articles

-

-

Priority access and subscriber-only discounts to courses, events, and more

-

Ad-free experience

-

Access to our Discord community

Comments

Don't have an account? Sign up!