Finding Power

An introduction to Clay Christensen’s most underrated idea: “The Conservation of Modularity”

People think strategy is about profit, but really, it’s about power. Profit is just the prize.

And if you want to understand the nature of power in business — where it comes from, how to create it, how to sustain it — probably the best place to start is Clay Christensen’s “Law of Conservation of Modularity,” a massively underrated idea from his second book, The Innovator’s Solution.

It’s pretty obscure compared to Christensen’s other hit theories, like “disruptive innovation” and “jobs to be done.” I think this is because the theory can be somewhat abstract and technical, making it hard to understand. (Don’t worry — in this article I do my best to make it engaging and intuitive! 😅)

Another reason the idea is obscure is it suffers from branding issues. Confusingly, it was originally called “The Law of Conservation of Attractive Profits” and some people still refer to it by that name.

But, despite all the challenges, this is not an idea you want to overlook. In my view, it’s actually the most powerful theory in Christensen’s entire oeuvre. I love it because it gives us a unique lens we can use to answer the most important question in strategy: why are some companies so much more powerful than others?

So let’s dive in :) 🔮

⎼⎼⎼⎼⎼⎼⎼⎼

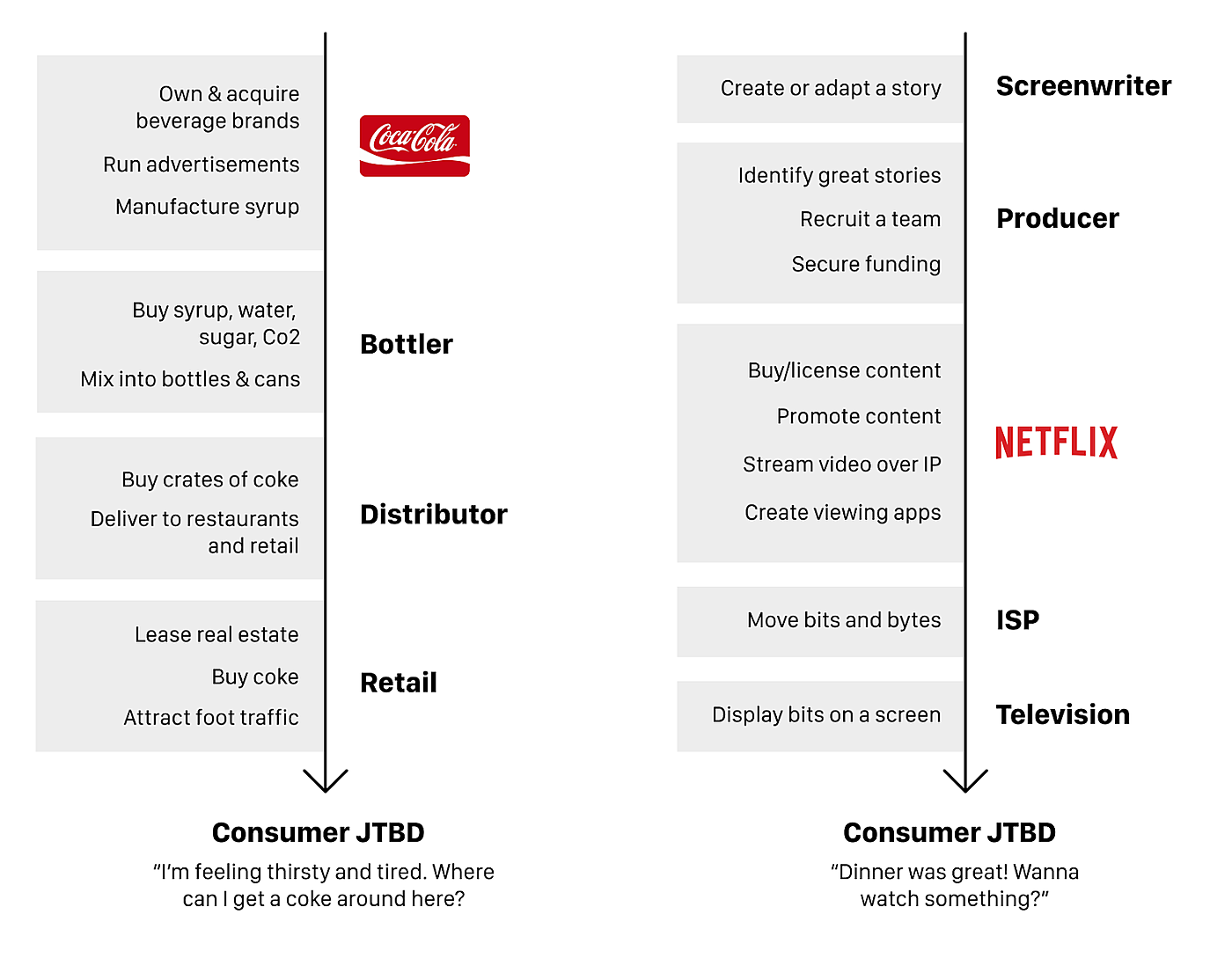

Every industry — the entire economy, in fact — is essentially a chain of interlocking activities that work together to transform raw resources into completed products. These “value chains” have evolved to serve the most common needs that arise in our lives.

For example, here are two value chains, built on two different consumer needs: refreshment and entertainment.

(JTBD = “job to be done,” which is Christensonian parlance for “need”.)

Of course, all these activities aren’t being performed solely to serve consumer needs. At every step in the process, businesses are trying to make as much money as possible. But they will not all succeed. Some positions in the value chain are destined to generate unimaginable wealth for the businesses that occupy them, while other positions are doomed to subsistence profitability.

This is a fact that we often take for granted. But really, stop to think about it: why do some companies make so much more money than others?

In my previous posts covering Michael Porter’s work, I covered the Five Forces framework, which is a good tool to measure how powerful a company is. The basic idea is that there are five forces that act on every company to limit power and profits. But it doesn’t explain why some companies experience so much more force than others. Obviously this is important information to know when you’re crafting a business’s strategy.

Lucky for us, it’s the exact question Clay Christensen aimed to answer with his “Theory of Conservation of Modularity.”

The key to predicting where power will sit in any value chain, Christensen realized, is to identify where you can improve the thing that’s most painfully lacking in the user experience. In other words: focus on what is not yet good enough. Make it better, and customers will love you, giving you power. Back away from the frontier of what’s possible, or perform activities in the value chain that don’t alleviate this pain, and soon enough your power will vanish.

“Uhhhh… that’s obvious!” You might say. “Build a great product that solves a real problem, and you’ll have a great business.” And it’s true — but it’s nowhere near the whole truth. We need to dig deeper to make it useful.

Here’s the thing: In order to improve what’s not good enough in the user experience, you need to have control over the layers of the value chain where the problems are. And, critically, you need to maintain that position, or find a new one if/when the problems move somewhere else.

For example, imagine that smartphones had terrible battery life, but the screens were more than good enough. You might think the screen-maker deserves attractive profits because they did a great job and solved a problem for consumers — but no! The opposite happens! In this world, it would suck to be a screen-maker. The screens are good enough, so nobody cares about any of their product improvements. When the most important problem in a value chain moves away from you, so does your power.

This point is so important it’s worth repeating: When the most important problem in a value chain moves away from you, so does your power.

So, what does this mean for our smartphone value chain, where the battery sucks but the screens are great? In this world, the phone maker would have the power to buy screens from any reasonable provider without their customers noticing the difference — which makes screens a pure commodity. Competition becomes solely based on price, and the phone maker gets to dictate all the terms and influence the screen design to help them solve whatever problem they are focused on, like improving battery life.

⎼⎼⎼⎼⎼⎼⎼⎼

The phone maker’s power to dictate the terms to the screen makers is really important. In order to optimize battery life, the phone maker will need a lot of control over all the subcomponents inside the phone. And the phone maker that is able to get that control — and wield it well — will tend to sell the most phones. Because they’ll have solved the most important problem (battery life) the most effectively.

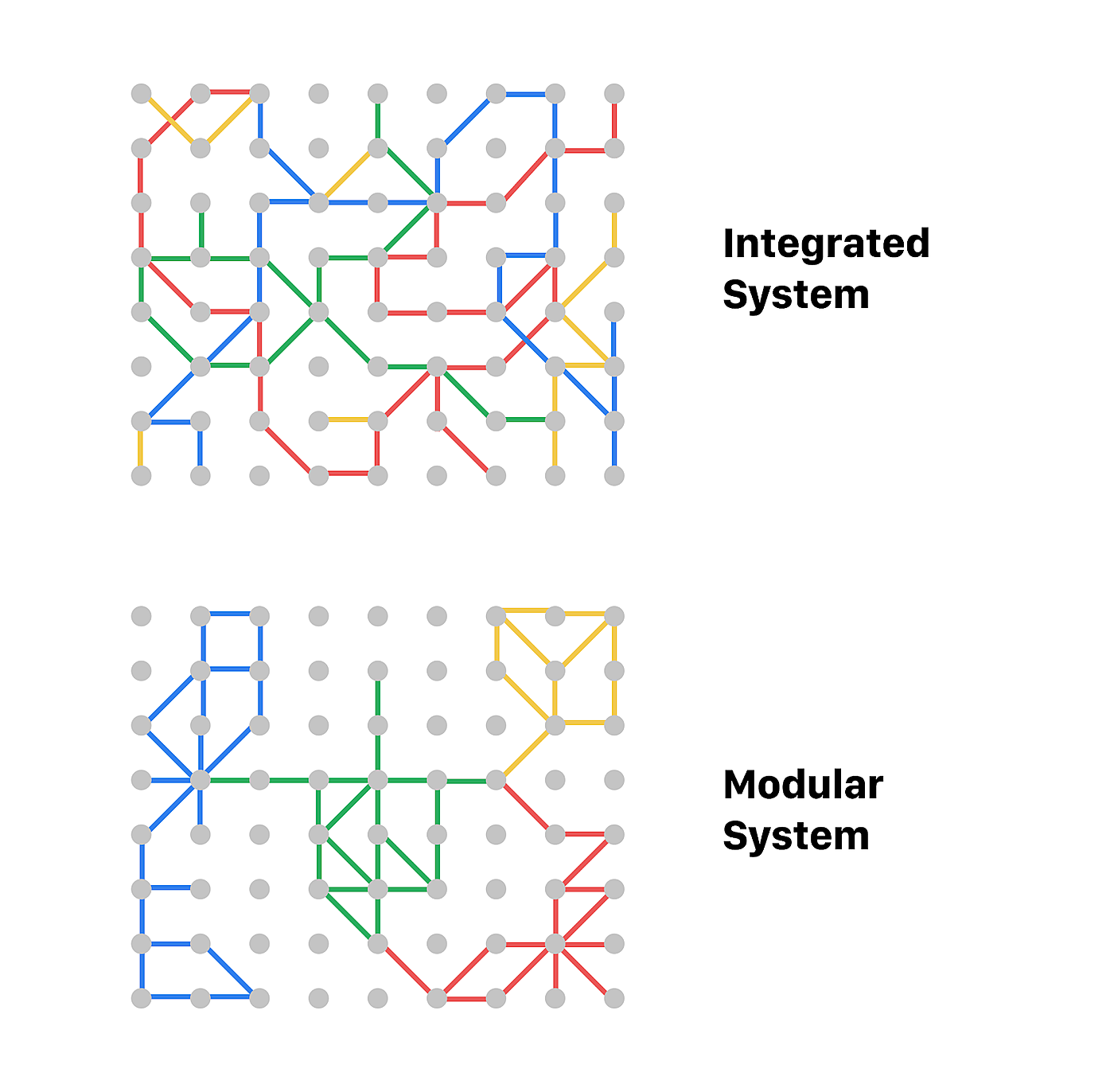

Clay Christensen would call the phone in this example an “integrated system,” and the screen a “commoditized module.” The distinction between integrated and modular can be somewhat confusing at first, but it’s actually pretty simple.

An integrated system has a lot of interdependencies. That means there are a lot of things inside that depend on each other, and if you try to separate them you run into problems. It’s like when you say someone is “really integrated into the community” it means they have a lot of relationships where they depend on others, and others depend on them.

A modular system, on the other hand, is made of clusters with lots of interior complexity, but relatively simple public interfaces. It’s like at a big company, where you have smaller teams with lots of internal integration, but externally they act as modules, with simple flows of inputs and outputs. Another example is our brains, which have “modules” full of dense networks of neurons, and relatively sparse connections between the modules.

What does the distinction between integration and modularity have to do with solving product problems? Well, improving any system is an act of integrating. You manipulate the connections between various components to make them work better together.

For example, the phone maker might come up with creative ways to improve battery life by dimming the screen in low-light situations. In order to do that, you need to integrate a light sensor, the operating system, and the screen’s backlight. If you don’t have control over all those layers, you can’t implement this optimization.

In any value chain, some companies own the important integrations, and others have to conform to what those integrators need. The way this works is simple: natural selection.

Imagine two value chains with two different architectures.

The first has a company that controls all the important layers needed to solve the most important problem. (For example, a smartphone maker that has sufficient control over the internals of the screen and CPU to optimize battery life.)

The second has a bunch of powerful module creators and a relatively weak integrator. (For example, a smartphone assembler that uses off-the-shelf components and doesn’t have enough control over them to fix the battery life problem.)

The value chain that will win is, obviously, the one that has a powerful integrator solving the problems that matter most to consumers. The other value chain might still exist to serve consumers that have different priorities (e.g. linux in the 90s), but it’ll be much smaller and weaker overall than the value chain whose architecture is better adapted to serve the mainstream market’s job-to-be-done.

In order to gain power, you want to control the layers of the value chain where performance is not good enough. You want to be the integrator. And — paradoxically — in order to keep that power, you’d better hope performance stays not good enough for a long time, despite the constant improvements you keep introducing in order to stay ahead of the competition.

You want your improvements to continue to matter to people. If not — if you become “good enough,” and the problems move elsewhere — then commoditization is inevitable.

⎼⎼⎼⎼⎼⎼⎼⎼

The idea of “good enough” is sort of counter-intuitive.

We’re taught that people have infinite demand and always want more, faster, better. But this is false. Do you want one thousand televisions? No, you don’t. If someone delivered them to your front door, you’d try to sell or donate them, and it would be an enormous hassle.

Ok, so maybe we don’t want infinite quantities of things, but what about quality? For example, what if you had one television with a picture so clear you couldn’t distinguish it from reality? You’d be happy to have it, sure. But how much extra would you pay? $100? $200? $800? There is a quantifiable limit to how much you value quality.

Of course, in some markets there’s a much higher ceiling for “good enough” than others. For instance, in the market for venture capital, there’s no such thing as raising money from a “good enough” firm. Startups overwhelmingly prefer to raise from the best. This is why a VC firm’s brand is so important. The same goes with entertainment. There’s no such thing as a song, book, or movie that’s too good. We’re constantly seeking the best.

Of course, this doesn’t mean we have infinite demand for what isn’t good enough. Most people wouldn’t pay $70 for a movie ticket, even for the best movie. And most founders wouldn’t offer a 70% valuation discount, even to the most reputable investor. But still, we’re willing to pay a bit of a premium in price and convenience to improve what isn’t good enough.

If not, then it turns out it actually is good enough.

One way Clay Christensen describes it that I like, is to ask whether buyers “are able to utilize” performance improvements. This makes it clear that performance is always relative to the customer’s job to be done. If it’s not useful for the job, it doesn’t matter.

⎼⎼⎼⎼⎼⎼⎼⎼

We’ve got some fun examples coming next, but first, let’s quickly recap what we’ve learned about the theory of “Conservation of Modularity” so far:

- Value chains evolve to serve consumer “jobs to be done”

- The biggest problem that most customers experience with the current value chain is the “basis of competition”

- The way to solve the problem is to control the layers of the value chain where the problems arise, and integrate them together in a new way that makes things better for buyers.

- Do this well, and you are in a potentially powerful position.

- As you gain adoption (and power), your partners in the value chain that live upstream and downstream from you will come under increasing pressure to modularize and conform to your needs, so you can keep improving performance for buyers along the basis of competition.

- If you overshoot buyers’ needs, your product becomes “good enough.” This is a dangerous situation, because the basis of competition could change, and the important integration you controlled could become less important.

Got it? Great!

(If not, that’s ok too! Keep reading or leave a comment. I’m here to help, and we’re all learning this together!)

⎼⎼⎼⎼⎼⎼⎼⎼

Ok! Now let’s consider the Coca-Cola and Netflix value chains from the diagram at the beginning of this article. They’re both the most powerful players in their value chains — but why?

It all stems from the activities they perform. Let’s explore them, starting with Coke:

Coca-Cola’s power is derived from their control over the integration between flavors and brands.

In other words, they are in charge of the formula that makes a Coke taste like a Coke, and they are in charge of the “Coca-Cola” logo. They “integrate” these things, meaning they make them work together. In this case, the integration is extremely simple: they advertise Coca—Cola, get it into stores and restaurants, and make sure that it always tastes the same.

(Integrations can create value in more complex ways, too, as we’ll learn with the Netflix example!)

Why is this integration important? What problems does it solve in the user experience? Well, imagine if every time you bought a Coke it tasted different. Yuck! So, obviously, the label needs to match the flavor, and if Coke didn’t integrate them, someone else would.

But, of course, a ton of other people do. There are millions of beverage brands! So what gives Coke an edge? A couple things:

- It is everywhere. Hard to love a soda you can’t ever find! Fun fact: when I was a kid, I loved an obscure soda called “Vernor’s.” Now I can barely find it anywhere, and I tried it recently and it wasn’t as good as I remember. Coke, on the other hand, remains a guilty pleasure. Familiarity makes flavors more enjoyable.

- You can’t improve on it much. You can create a different flavor, but it’s pretty much impossible to make something most people experience as categorically better. But the best part is, even if people start to prefer something different, Coke can identify the shift, buy a leading brand, and leverage its scale to accelerate the trend. (Did you know Coke bought Topo Chico, the best sparkling water? Now you do.) Even if Coke the soda loses, The Coca-Cola Company can still win.

- Advertising works, and because Coke is the biggest, they can out-spend the competition. They can ruthlessly associate their logo with sensations of warmth and joy in your brain. And the next time you see a Coke in a fridge, you’ll subconsciously gravitate to it, giving them a bit more money to spend on ads. This is a virtuous cycle that can run forever.

Over time these choices propagate through generations, and a slight initial preference (perhaps more thanks to luck than merit) snowballs, and becomes imbued with memories of people you love and activities you enjoy. So the brand gets even stronger, and it’s all tied back to that, admittedly, somewhat arbitrary flavor and logo integration that Coca-Cola owns.

So, that’s why Coke has an advantage over direct competitors, but what about the other players in the value chain? Aren’t they just as important? I mean, syrup is worthless until it’s mixed with sparkling water and sugar and delivered to consumers. So shouldn’t the bottlers, distributors, and retailers have a lot of power, too?

In short: no.

Bottlers don’t have much power because bottling innovations don’t matter to consumers. The bottle is already good enough, and consumers couldn’t tell at all if you switched out one company for another. (Swap out the flavor on the other hand, and… remember New Coke?)

This gives Coca-Cola the power to tell bottlers exactly what to do. They specify the design of the bottle, the manufacturing process, the geographic region they’re allowed to sell to — everything. If the bottler wants to do it a different way, Coke says, “Fine, invent your own soda brand,” and the bottler says “Ah sorry nevermind.”

The result is that bottlers are totally unable to differentiate their product. The only thing they can do is try to increase efficiency, but most of these gains just get copied by competitors, and prices drop to a new low. When you look at the numbers, it bears this story out: Coca-Cola has a 27% net income margin, and their largest bottler only has a 0.25% net income margin. Ouch!

Distributors are in the same boat. Their job is to buy a lot of different beverages, and sell them to a lot of different stores. It’s a nice service, and they may have some regional power, but of course nowhere near enough power to outweigh the consumer’s desire to drink Coke. So they too are forced to buy Coke products, on Coke’s terms.

What about retailers? Some of them can be good businesses! Wal-Mart, Amazon, Kroger, and Dollar Tree are all fairly healthy, thanks to their own unique mix of price, assortment, location, and experience. They integrate these components in unique ways to appeal to specific consumers in specific circumstances. But all of them would suffer if they refused to stock Coca-Cola.

For example, it was so hard for Pepsi to get placed in fast food restaurants, who often have exclusivity agreements with Coke, that they resorted to buying them! In the 70s and 80s Pepsi bought Pizza Hut, KFC, and Taco Bell basically just as the cost of doing business, so they wouldn’t get totally locked out of the fast-food market and they could force some people to drink Pepsi once in a while.

The Coke story is a great example of how sometimes when you own a critical integration you can defend it for decades. But that’s not always the case. Sometimes changes in technology or society create opportunities for the critical integration to shift.

There’s perhaps no more interesting example of this than Netflix:

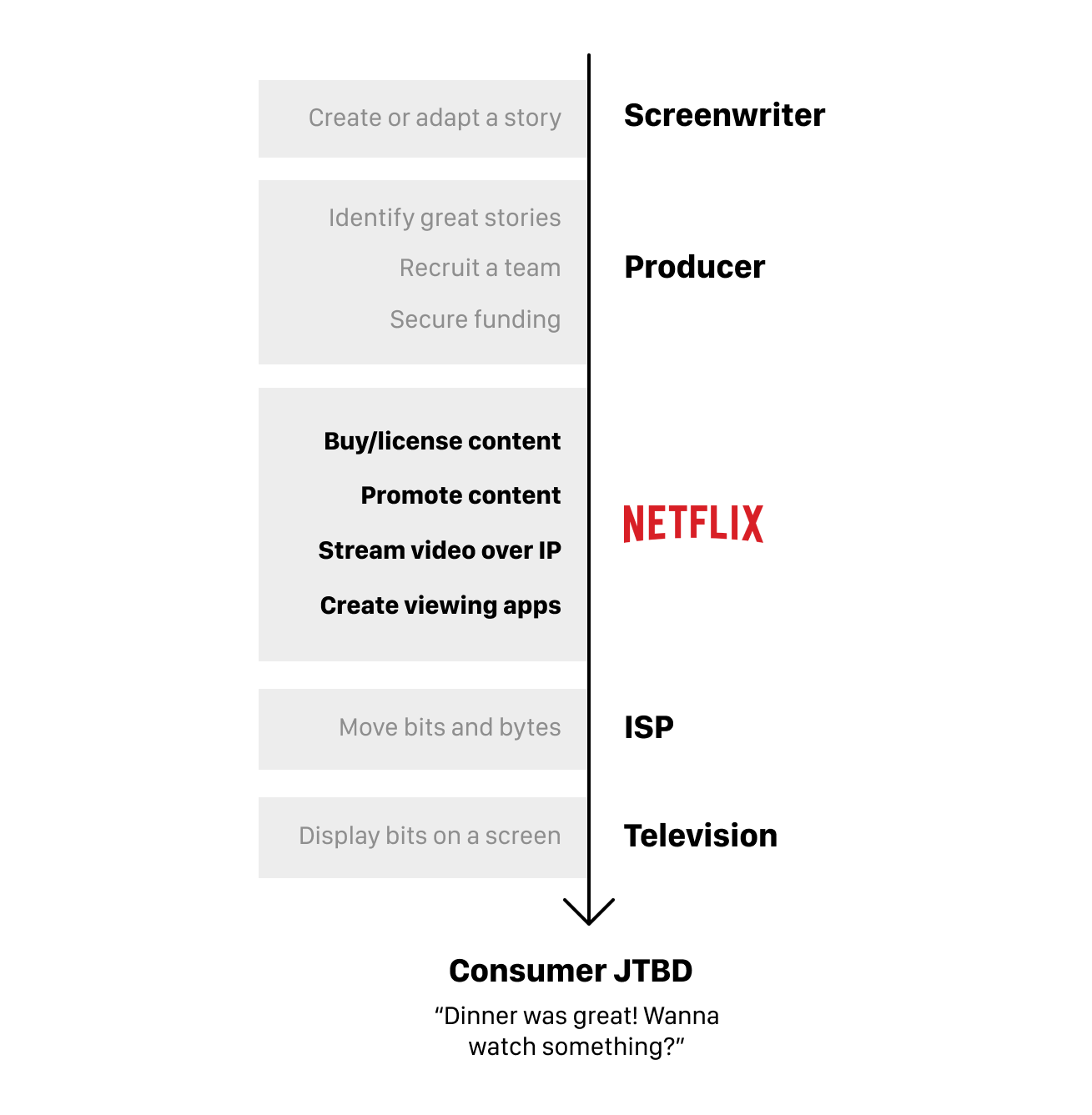

Netflix’s power is based on their control over the integration between content and viewing apps. In order to understand why, we need to go back in time and paint a picture of the way things used to be.

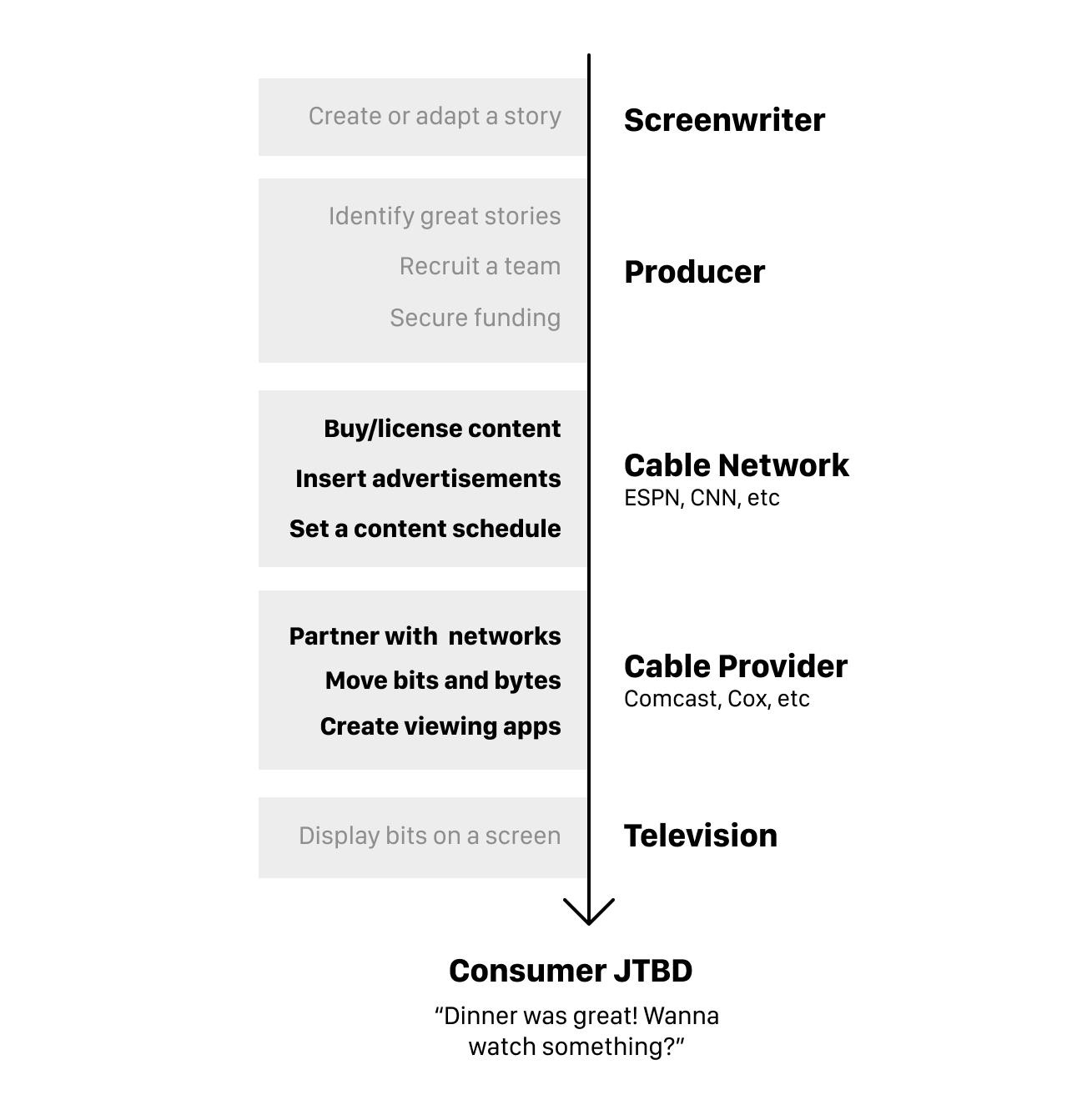

Before “the golden age of television” and “the streaming wars” and all that, the “watching tv at home” value chain was dominated by Cable Providers and Cable Networks:

In this world, the people buying the content (cable networks) had to conform to a very constrained interface defined by cable providers and TV manufacturers. The networks were free to use their airtime pretty much however they wanted, but their only output was a live video feed. The cable company then integrated these feeds into our television sets, and gave us a remote control to choose what channel we wanted.

But of course, there was a problem: the content wasn’t good enough. In fact it can almost never be good enough. There’s always the possibility of more compelling plots and characters, more topical coverage, better aesthetics, etc. And what’s good to me won't necessarily be good to you. So people wanted more quality, choice, and personalization.

At first the cable companies responded by increasing the number of channels. Instead of 30, you got 60. Then 90. Then 300. But it still wasn’t enough. What if you finished dinner at 7:40, but your favorite show started at 7:30? Too bad.

To solve this, we got TiVo and other generic DVRs, but you had to schedule shows to be recorded (planning ahead? yuck!) and you were still functionally limited by the constraints of linear TV. Most shows weren’t created with the assumption that people could start from episode 1. So, in order to conform to the limitations of cable providers, they were “episodic,” meaning each episode was modular and mostly stood alone. It didn’t require you to have prior knowledge of the plot or characters — which raises the floor but also lowers the ceiling of entertainment value.

So performance was improved by adding more channels and adding TiVo, but it was still not good enough. At a certain point, browsing through hundreds of channels becomes pointless. Finding the stuff you like becomes a pain. Also, the “episodic” content itself was suboptimal. The internet was growing, it became clear a better way was possible.

Enter Netflix.

The internet eliminated the old constraint of linear television, and made everything on demand. Selection all of a sudden felt infinite. You could start a show from episode 1, and binge watch it through to the end. You could browse through an interactive menu driven by an AI recommending just the stuff you’re most likely to love, with trailers for each show designed to entice you in just the right way. You could start and stop anything, whenever you want. Even if it was 7:40. Even if it was the middle of the night! No more infomercials!

If Coca-Cola’s power is derived from their integration of flavors and brands, Netflix’s power is derived from their integration of content and screens. Because they own everything from the content to the user interface, and they utilized a new technology to deliver a superior experience, Netflix was able to solve the biggest problem with TV: selection.

The result... wasn’t actually that good at first. There were several problems: it was hard to view on your TV, internet speeds weren’t fast enough, picture quality was bad, and Netflix’s selection of stuff to stream was relatively weak. But the basic architecture of their experience was so fundamentally superior that it began to take hold anyway, and the flywheel started to turn. More viewers → more money → more content → better recommendations → more viewers.

The loop keeps spinning, and Netflix is now worth $185 billion.

Now, instead of the industry conforming to fit the standards set by the limitations of cable providers and television sets, the tables have turned, and television sets are now modularized and must conform to work well with Netflix! And the same thing happened on the upstream supply side, too. Hollywood has re-shaped itself to better suit Netflix’s needs.

⎼⎼⎼⎼⎼⎼⎼⎼

I hope you can see why I love this theory so much.

It’s not the only tool a great strategist needs, but it feels like one of the most essential ones. Like I said at the beginning, it can be complicated and technical, but that doesn’t make it any less valuable.

Before we go, there’s just one thing left to explain: the name.

Why call it “conservation of modularity”? What exactly is being conserved? This is hard to see without understanding the rest of it, so I saved it for the end. And it’s actually a really beautiful idea.

The “conservation” part is a reference to an idea in physics called “the conservation of energy,” which states that energy cannot be created or destroyed, it can only be transformed. So, if you were to punch a punching bag, for example, the energy in your arm would transfer from your arm to the bag, making it swing.

So what does that have to do with business?

There is a certain amount of power in every value chain, and that power cannot be created or destroyed, it only can be transformed. The power is a reflection of who controls the important integration point, and who is providing a less-important modularized component. Therefore, if the important integration point shifts (as was the case in the Netflix example), then the layers of the value chain that used to have power will lose their power, and they must modularize and conform to what the integrator needs. (As was exactly the case with cable providers and television sets.)

Thus: modularity, power, and profits are all “conserved.”

This is exactly the kind of thinking that makes me love Clay Christensen so much. He genuinely believed that the study of business could make progress closer to other areas of science.

It’s a belief that inspires me and is my main reason for writing Divinations.

⎼⎼⎼⎼⎼⎼⎼⎼

Two last things before we go:

- If you liked this, hit the purple “Like & Comment” button below! It will let me know whether I should write more stuff like this or not.

- Are you interested in using this framework to analyze a specific value chain / job-to-be-done? Leave a comment and say what vertical you’d like to study! I’d love to publish what you write, and turn Divinations into more of a collaborative research project than a one-way channel.

Thanks!!

⎼⎼⎼⎼⎼⎼⎼⎼

Acknowledgements:

- Thanks so Dan Shipper, Paul Smalera, Adam Keesling, and Jacob Donnelly for reading drafts of this post. It would have much worse without your feedback!

- Ben Thompson introduced me to this theory, and I have to give him credit for it. His work on this topic is seminal. If you’re interested in diving deeper, I recommend reading Netflix and the Conservation of Attractive Profits and listening to From Intel to Disney.

Find Out What

Comes Next in Tech.

Start your free trial.

New ideas to help you build the future—in your inbox, every day. Trusted by over 75,000 readers.

SubscribeAlready have an account? Sign in

What's included?

-

Unlimited access to our daily essays by Dan Shipper, Evan Armstrong, and a roster of the best tech writers on the internet

-

Full access to an archive of hundreds of in-depth articles

-

-

Priority access and subscriber-only discounts to courses, events, and more

-

Ad-free experience

-

Access to our Discord community

Comments

Don't have an account? Sign up!

Great article! I'm wondering about the Coca Cola example. I think it is an interesting and powerful one to work through through I feel like I'm missing something - Has the Coke process not reached "good enough"? It seems well past that point (in fact they can NOT change it anymore...). Other drinks have even done very good copies of the Coke test (whether people will admit it or not...). So it seems that the key element that is maintaining their power is shear dominance of the brand. Brand strength with the target market (particularly that strength in relations to competitive solutions) seems to be a universal asset of nearly any point on the value chain. If you are commoditized (or "modularized") but are able to maintain brand dominance, you can maintain power. Obviously brand dominance is not easy since its essentially a zero-sum winner-take-all type of game.

In the other example with Netflix, even though the networks and providers were dominant, their brand strength was dismal, providing an opening for Netflix in spite of the technical challenges they faced. There were also so some very deep pain points as you mentioned.

In fact, going back to Coke, in order to maintain that type of loyalty and dominance, there can't exist any pain points too deep on the value chain. If something comes up as too painful, brand loyalty will wain with a new search for a "painkiller." The soda industry may just be too "good enough" over the entire value chain, not allowing for any innovation to occur or be necessary (aside from the branched market developments like energy drinks, etc. which they address through acquisitions as you mentioned).

Just working through my thoughts... Am I missing something else with the Coke example?

Awesome piece. I have bookmarked it.

Great article. Your passion for this type of thinking really shines through. This has really helped me articulate my thinking about Strava and the issues it faces due to its position in the value chain.

Wow, a really useful concept to understand. Your explanation is clear. The examples are super helpful.The balance between solving a problem, but not solving it so well that it ceases to matter, is interesting. You can't really control this. If you don't solve a problem, someone else will. Just hope that it stays somewhat unsolved.

A vertical I'd like to see analyzed is 'how-to' or informative content. I think up to now, distribution has had all the power (i.e. platforms). But TikTok developed creator tools and were able to build a competing distribution network. Is it possible that power is about to shift to inspiration/creation workflows?

This is an amazing article and concept. Actually, as I understand it, it sits at the heart of "Choosing your Market and Model", if you start or transform a business.

I am building a Business Accelerator, which is why this super interesting to me to understand. I'd love to dive deeper into strategy around this! What would you recommend I get into next, if the only thing I'm concerned with is Business Strategy and Leadership? Would love to have a chat with you and find ways to map these concepts to real-world application just as you did with Coca Cola and Netflix!

drug development or life sciences devices