Sponsored By: Vanta

Ready to simplify security? Vanta can give you up to 400 hours of your time back and an 85% cost savings. Learn how Vanta helps companies scale security practices and automate compliance in their on-demand product demo.

There are two ubiquitous pieces of advice on how to prioritize a product roadmap. Unfortunately, both are useless.

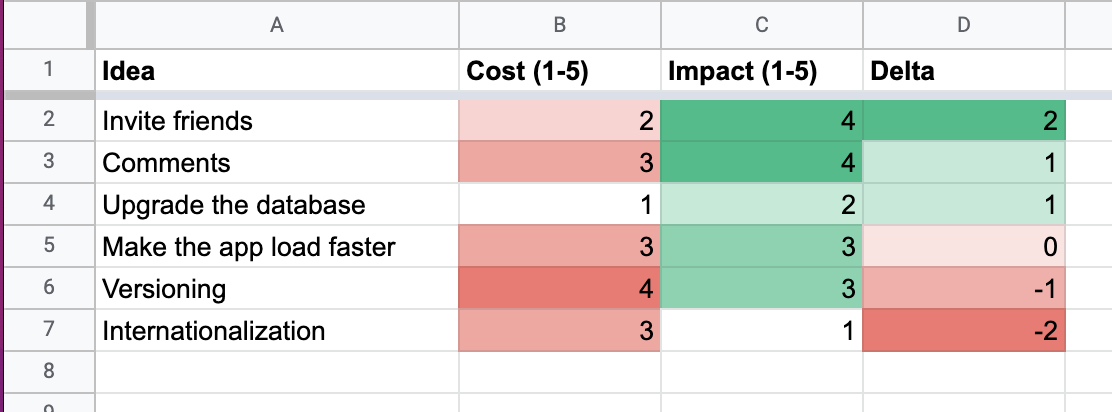

The first is to create a spreadsheet to list all your ideas, and score each one by how much it will cost to build and how much impact it will have. Then, sort them so that the ideas that have the most impact for the least effort show up at the top, like this:

There are a million variants of this framework, but none of them helps you with what is hard about prioritization: coming up with good ideas and accurately predicting what would happen if you decided to pursue them. When you’re filling out numbers in a spreadsheet, it can feel like a shot in the dark.

When asked how to deal with this problem, experienced product leaders will often proffer the second piece of ubiquitous-yet-useless advice, saying something along the lines of, “It’s more art than science” or, “Just go with your gut.”

Is there anything we can learn that helps us get better at prioritization?

I have 10 (hopefully non-useless 😏) theses that help us understand why prioritization is hard, and how to get better at it.

1. Prioritization isn’t about prioritization

You don’t get good at prioritization by learning frameworks to help you sort a list of ideas. Instead, you master it by learning general and domain-specific business knowledge. Efficacy is mostly a function of talking to customers to understand what they want, or talking to engineers and designers to understand how your product is architected, or learning new techniques from research or peers. Once you know these things, prioritization is easy. Without them, it’s impossible.

VantaCon 2022 brought together the most innovative minds in security and compliance. And now, we're excited to share recordings of the keynote, breakout sessions, product details, and more! Learn from industry leaders in security, finance, and healthcare. Be sure to sign up to stay in the loop for VantaCon 2023.

2. Prioritization is where every skill related to company building converges into a single choke point

Engineers will bring their perspective about how the codebase is scaling. Designers will focus on all the confusing and inconsistent parts of the UI. Product managers will come with AB test ideas to move the metrics they’re responsible for. But in order to decide what should be done (and what shouldn’t), someone has to integrate all this knowledge.

3. Generalists beat specialists at prioritization

This is a corollary of the first two theses. It’s hard to integrate knowledge from several domains if you only know anything about one of them—hence why it’s common at large tech companies for PMs to have technical backgrounds, and startup founding teams with technical and industry-specific DNA tend to outperform teams that outsource.

4. Prioritization decisions are hard to explain

Asking a world-class startup founder how they prioritize the roadmap for their company is like asking the DeepIris algorithm how it is able to classify a photo of an eyeball as belonging to a male or female human being with 98.88% accuracy: there is no simple answer. These decisions depend on a multitude of factors and personal experiences.

So don’t be surprised if it’s hard to get easy or satisfying answers to questions about why one idea is a priority while another is not. Be willing to go deep.

5. Garbage in, garbage out; diamonds in, diamonds out

If you don’t have any good ideas in your list, it doesn’t matter how effectively you prioritize them. (This might seem obvious, but most people don’t spend enough time on ideation.) Conversely, if your list of ideas is full of bangers, prioritization doesn’t matter that much. Therefore you should spend much more time doing the work to come up with good ideas than thinking about how to order them.

6. Starting from business goals is dangerous

When you’re building a roadmap, there are two main sources of ideas:

- Problems customers have (e.g., write faster)

- Goals the business has (e.g., build a network effect)

It’s better to prioritize ideas that come from the first source. When you start with things customers need, you’re much more likely to build products of actual value, rather than get strategy-drunk and embark on misguided projects.

Of course, business goals are important. But you’ll be more successful if you start with customer problems and sort them based on their estimated impact on business goals, rather than letting business goals drive product ideas.

7. Big leaps aren’t always worth it

When evaluating ideas, it’s easy to fall into the trap of thinking you should only do “big ideas.” Usually this means a flashy new feature that you could imagine announcing to great fanfare.

But often early-stage products are bad because they’re confusing, buggy, and/or slow. It’s by no means a given that you should embark on a big, flashy project in order to grow faster. Perhaps you’d be better off polishing what you have. You’d be surprised how much you can move the metrics with seemingly small ideas.

8. Beware the streetlight effect

Let’s say, hypothetically, you’re building an AI-focused writing tool. You know if you build collaboration features it will increase your growth rate because it will induce people to invite others into the product. But you also know that those collaboration features won’t matter if the core value—the way AI is integrated into the writing experience—isn’t as solid as possible. So it makes sense to focus on these features, even if they have less of an obvious 1:1 correlation to growth than some others.

This is a perfect example of the streetlight effect—the tendency to search for things we want only where it is easiest to look. The name “streetlight effect” comes from the joke about a policeman finding a drunk looking for his keys beneath a streetlight at night, because that’s where he can see, even though he says he lost them in the park.

There are certain types of ideas that have an impact that is hard to measure. In low-trust teams (more on this in thesis number 10), these ideas never get done even when they’re obviously important because they’re too hard to justify compared to “streetlight ideas,” like revamping a viral invite flow.

9. Define an organizing principle

When anything goes, it’s impossible to choose between competing alternatives. There must be some strategic frame against which to measure ideas. But too often, the framing of this goal is taken for granted. Startups obsess over weekly growth rates, and public companies obsess over margins—but these are goals, not strategies. The best companies choose narrative frames in addition to measurable goals that help them stay focused.

For example, at Substack we cared about week-over-week growth like everyone else, but we also had organizing principles like “attract quality writers who are ready to go full-time on paid newsletters” that helped us organize our roadmap. For Lex, our current organizing principle is to build the best “first draft” writing experience in the world. If we only thought about the metrics we would be lost.

10. Prioritization is about trust and alignment

It may seem like the most important output of a prioritization process is a plan for what ideas to tackle in what order. But what’s more important is the shared understanding created within a team by going through a prioritization process together.

As Eisenhower said, “Plans are worthless, but planning is everything.” When we finish planning and start doing, the world will inevitably throw surprises at us. We’ll have to adjust as we go. But by having hard conversations as a group, we'll be prepared to handle those contingencies.

Even if everything goes more or less to plan, we’ll be able to execute more effectively when everyone understands and is aligned on the strategy. And the only way to get a group to truly understand a strategy is to go beyond a high-level articulation and show what it means when hard decisions about resource allocation trade-offs are faced.

Find Out What

Comes Next in Tech.

Start your free trial.

New ideas to help you build the future—in your inbox, every day. Trusted by over 75,000 readers.

SubscribeAlready have an account? Sign in

What's included?

-

Unlimited access to our daily essays by Dan Shipper, Evan Armstrong, and a roster of the best tech writers on the internet

-

Full access to an archive of hundreds of in-depth articles

-

-

Priority access and subscriber-only discounts to courses, events, and more

-

Ad-free experience

-

Access to our Discord community

Comments

Don't have an account? Sign up!