The Unreasonable Effectiveness of 1-1 Learning

How to learn anything 98% better than average

August 6, 2022

Education is expensive because you’re paying for more than learning. You’re paying for the status of the degree, the ability to participate in the community, a planned course list and curriculum, the quality control that the university provides, and on and on. You’re paying for a turn-key, minimum effort experience.

But if, for some reason, you don’t care about those things and you’re optimizing primarily for learning—you can learn anything 98% better than you would in a class, for significantly less money. The way to do this is through 1-1 tutoring.

I know this because I did it. A few years ago I decided I wanted to write a novel. So I had the author of one of my favorite books tutor me on fiction writing. I made more progress during those tutoring sessions than I had in workshops, classes, and solo learning combined. And I spent far less money on it than I would have spent on an MFA.

And that’s not an accident. One of the most famous studies in educational psychology found that students who learned through 1-1 tutoring performed two sigma—98%—better than students who learned through a traditional classroom environment.

You can do this too for the topic of your choice. You just have to put effort into finding the right person, and into working with them. It won’t be an out of the box experience like a class. You have to be willing to bring a lot more to the table than you would ordinarily.

But you’ll learn a lot more than you might otherwise, without spending a lot of money. Let me explain.

. . .

I decided I wanted to write fiction in 2016. At first, I thought this would be fairly easy: I’d just sit down and write every day and eventually a great work of fiction would come out. I’d been writing for a long time on the internet so this seemed reasonable.

It turns out, though, that writing fiction is an entirely different beast than writing blog posts. You need to learn about scenes and structure and dialog and character development and plot and a thousand other things. When I realized this it was quite exciting to me; I dove in head first.

I picked up the Aaron Sorkin MasterClass on screenwriting (for witty dialog) and read Scene and Structure and Elements of the Novel and ten other books. I took diligent notes and tried to apply what I read to my writing practice. I got better, and I churned out a lot of pages of material, but I still didn’t make the progress I wanted to.

So I tried a class. As a kid I’d seen the yellow Gotham Writers Workshop boxes around the city:

So I signed up for their Fiction Writing I class. This time there was a real live teacher there who had published his own novel. There was a structured curriculum, and homework, and 20 other students to workshop my writing with. I got even better. I did another class.

But I still felt like something was missing. I was in a different place with my writing and my career than the rest of the students, and my questions and problems were different. It’s not that I was better at writing, but I had a set of skills that I knew were lacking and specific problems in the draft of my novel that I wanted to try to solve—and the classroom environment wasn’t tailored to those things.

I thought about doing an MFA, but it seemed really time consuming and expensive. I wanted to get better at writing and to finish my novel, not get a degree. So that’s when I had the idea to try to get an author to tutor me. I had someone specific in mind.

A year or so previously I’d read a book called See You in the Cosmos by Jack Cheng that blew my mind. It was exactly like the kind of book I wanted to learn how to write in terms of character, structure, and voice. I’d talked to Jack once via a friend of a friend, so I had his email.

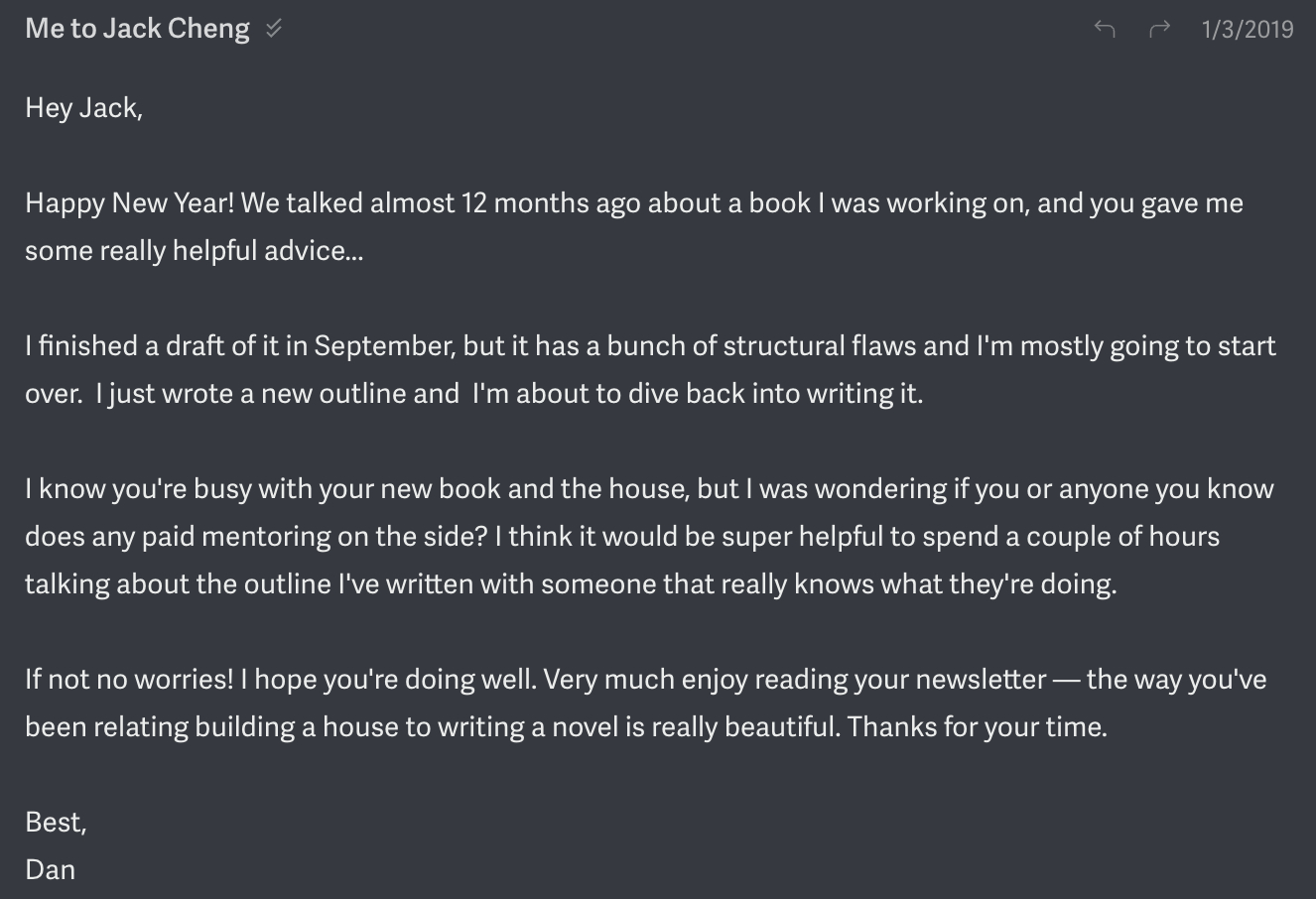

So, I decided to ask if he’d help me out. Here’s the email I sent:

He replied back, and said yes! We negotiated a rate and we were off to the races on my Personal MFA. And as I mentioned, I learned way more about writing—and made more progress on my novel—than with any other method of learning I’d tried up to this point. The reason is simple: I’d already done a lot of work on my novel, built up a decent amount of skill, but I was stuck in a few places and didn’t know how to build skill around them. Jack could help me identify where I was stuck and suggest things to try that would help—and he often solved problems with a few minutes of his time that I had been banging my head against for a year.

1-1 tutoring is extremely valuable, but it’s totally different than taking a class. I had to bring a lot more to the table to get what I wanted out of the experience. When you’re doing tutoring with someone who doesn’t teach professionally they won’t have a course structure or plan. So I had to suggest a structure, bring work in that I wanted to review, identify skills I wanted to build, and follow through by making progress on my own between tutoring sessions.

I learned a lot through this experience with Jack that I think is applicable no matter what you want to learn. So, let’s talk about how to do this, how to structure it, and what to expect.

. . .

Finding Tutors

The ideal tutor is someone who is far enough into their career to be able to teach, but not so far that it’s not worthwhile for them to spend time with you. If you want to learn any kind of academic topic then someone pursuing a master’s or a PhD in that area is an ideal candidate. Same thing for someone in the arts—a recent MFA grad, or someone who has just started to create successful work in their field might be interested in this.

A few ways to find people:

Find a piece of work you admire and email the creator. Obviously, this isn’t going to work if you email Aaron Sorkin about screenwriting advice. But if you find a book, or a photograph, or an academic paper written by someone who is relatively early in their career, then the chances are good they might be willing to help you. Even if they themselves aren’t willing to tutor you 1-1 you can ask them to refer you to someone else who might.

Look through university departments. Most universities post the names of grad students in different labs and research groups on their website along with contact details. Many of those people might be interested in doing tutoring. If you’re a fan of the research coming out of a specific lab, just email those people directly and see if they’d be interested.

Use the email I sent to Jack (pictured above) as a template for your outreach.

What You Need to Bring to the Table

When you pay for a class you get to show up as you are. A lot more responsibility is put on the teacher to design a curriculum that will take you from zero to knowledgeable about the subject so long as you follow their directions.

This isn’t the case with the kind of 1-1 tutoring we’re talking about here. First of all, if you’re working with someone who is a professional in their field you’re going to demonstrate that you’re worth their time. Sure, you’re paying them, but teaching isn’t their full-time job. They’re much more likely to find it appealing to tutor someone who has some basic knowledge and demonstrated willingness to expend effort in a subject area than someone who is coming in completely cold.

Second, if your tutor isn’t a professional teacher, expecting them to come up with a syllabus and a plan for a “course” might be a tall order—so instead you’ll need to take charge of what you want to learn and why. Having some basic background knowledge will give you an idea of what’s confusing and what you want to get out of your experience. This will allow you to guide the tutor in the right direction.

So before you get a tutor, try to get somewhere on your own first. Not only will this make you more likely to be able to work with someone that has a decent amount of knowledge and skill, it will also better prepare you to get something out of working with them. You’ll be able to come into your tutoring sessions with specific questions, or things you want to learn about which will make the process significantly more efficient than coming in cold.

This might seem like a lot of work—and it’s not for everyone. If you want to do less work you might consider paying for a class, or paying more for a tutor with higher expectations about what they’ll bring to the table. There are lots of options and degrees of freedom in how you structure things.

Pricing

It’s actually quite common for people who are getting started in an academic or creative career to teach in order to help support themselves. Unfortunately, they’re usually only teaching through a university or some other large organization that charges students a lot and pays the teachers very little.

By going directly to whoever you’re working with you can pay them a fair price that’s likely more than they would get teaching through a big organization, but is far less than you would pay to be a student.

Depending on the skill level and subject area, it shouldn’t be too hard to find someone who costs something like $50-$100 an hour. My recommendation is, once someone has agreed to do tutoring, just ask what they think is reasonable—and if it’s something you can afford go with that.

Structure

When I worked on my novel with Jack we met together every 2 weeks for four months. Every two weeks was nice because it gave me time to do a revision of a scene, and would give him enough time to review it before we met again.

Once the initial four month period was up, we re-upped for another multi-month commitment. I liked having a set end date because it gave us both a period to reflect on whether the arrangement we’d come to was good for both of us.

After a while of doing 1-1 sessions, I found it very useful to concentrate on learning one specific skill—like dialog—at a time, and then move on to another one when I felt I’d sufficiently improved. This one-at-a-time approach also works if you’re learning something that’s less skill-based and more knowledge-based.

If you try to learn everything at once it’s going to feel overwhelming and take away from your felt sense of progress.

What You Can Learn

I think there are at least three kinds of things you can learn from 1-1 tutoring (and you’ll often be blending them):

- Learning a field

- Building a skill

- Refining a piece of work

When I was writing my novel I was doing 1-1 tutoring to refine a piece of work, but in order to do that I had to do a lot of skill building. But I think there are lots of other places 1-1 tutoring can help.

For example, for my next foray into this world I really want someone to teach me how to read scientific papers. Right now, I can understand enough to get by—but there’s a whole layer of X-Ray vision that academics can apply to understand whether a paper is good, what its flaws might be, and what the takeaways are that I’m just not exposed to as someone not reading them in a university environment.

But there are lots of other things you might expect to learn via this method.

Summing Things Up

We all know that 1-1 tutoring is a good way to learn. But there’s a far higher supply of people who might be willing to teach you the subjects that you’re interested in than you might expect.

All you have to do is find them, ask if they’d be open to it, and be prepared to put in the work to take advantage of their time if they are. It’s worth it, I promise.

Find Out What

Comes Next in Tech.

Start your free trial.

New ideas to help you build the future—in your inbox, every day. Trusted by over 75,000 readers.

SubscribeAlready have an account? Sign in

What's included?

-

Unlimited access to our daily essays by Dan Shipper, Evan Armstrong, and a roster of the best tech writers on the internet

-

Full access to an archive of hundreds of in-depth articles

-

-

Priority access and subscriber-only discounts to courses, events, and more

-

Ad-free experience

-

Access to our Discord community

.jpg)

Comments

Don't have an account? Sign up!