How to write a bestselling book with a friend (even when it’s hard)

And you both have full-time jobs

June 18, 2022

Sponsored By: Mem

Tired of being so "organized" that you can't find anything?

Most digital workspaces rely on folders, tags, and hierarchies for organization. But that just is not how brains work.

Mem puts your meeting notes, documents, emails, and more in context using cutting-edge AI technology. Working with your brain (not against it) to surface what you need, when you need it.

Break free from folders, hierarchies, and decision fatigue. Unlock a serendipitous, self-organizing workspace.

Liz and Mollie finish each other’s sentences—in work and in real life.

They just co-wrote and illustrated their second best-selling book, Big Feelings, How to Be Okay When Things Are Not Okay. They’ve built a flourishing creative partnership that’s lasted through years of professional and personal changes and upheavals. And they’ve done it all while balancing the demands of having full-time jobs in different fields.

I wanted to understand: how do they do it? How do they produce great work—together—while working full time?

So we sat down to talk about the story of their books: the systems and processes they use to write them together. We talked about how they find time for creative output in the mornings and on the weekends, and how they tackle different pieces of the book simultaneously—and switch back and forth until each piece is finished.

As we talked, I realized that in order to understand their process for writing, I really needed to understand their partnership. For them, the great partnership is the process that makes the great books.

By the time a book is ready to be published, they say, they can’t point at a sentence in it and say, “That was mine.” It’s all theirs. And you can tell by the way they are in an interview: they obviously know each other, they know their similarities and their differences, and they fill in the gaps for each other in conversation seamlessly.

Partnerships like this are exceedingly rare in the creative world. So I wanted to know:

How did they find each other? How did they decide to work together? And why does what they do work so well?

You might think their partnership is great because of how similar they are. But they’re actually quite different in how they approach writing, and what they care about. Instead, it works because they’ve learned to be radically committed to using their differences—the bumps, and conflicts along the way—to create the best possible work.

What they’ve learned has enormous implications for anyone who wants to do their best work as part of a partnership, or a team. This is the story of how Liz and Mollie do it. Let’s dive in!

How They Met

Liz: I had just moved to New York from San Francisco for a job and felt alone and overwhelmed. I had never lived in New York before and I was afraid everyone was going to be abrasive.

I emailed everyone I knew and asked to be set up on friend dates so that I would have a softer landing in the city. Mollie was one of those first friend dates, and we just hit it off.

We’re both introverts. We both have intensive sleep routines: sleep masks, white noise machines, ear plugs. The whole thing. We also both had similar experiences of getting seemingly great jobs that we thought we’d be at for a long time—and then completely burning out.

So we bonded over those things initially.

How They Started Working Together

Mollie:

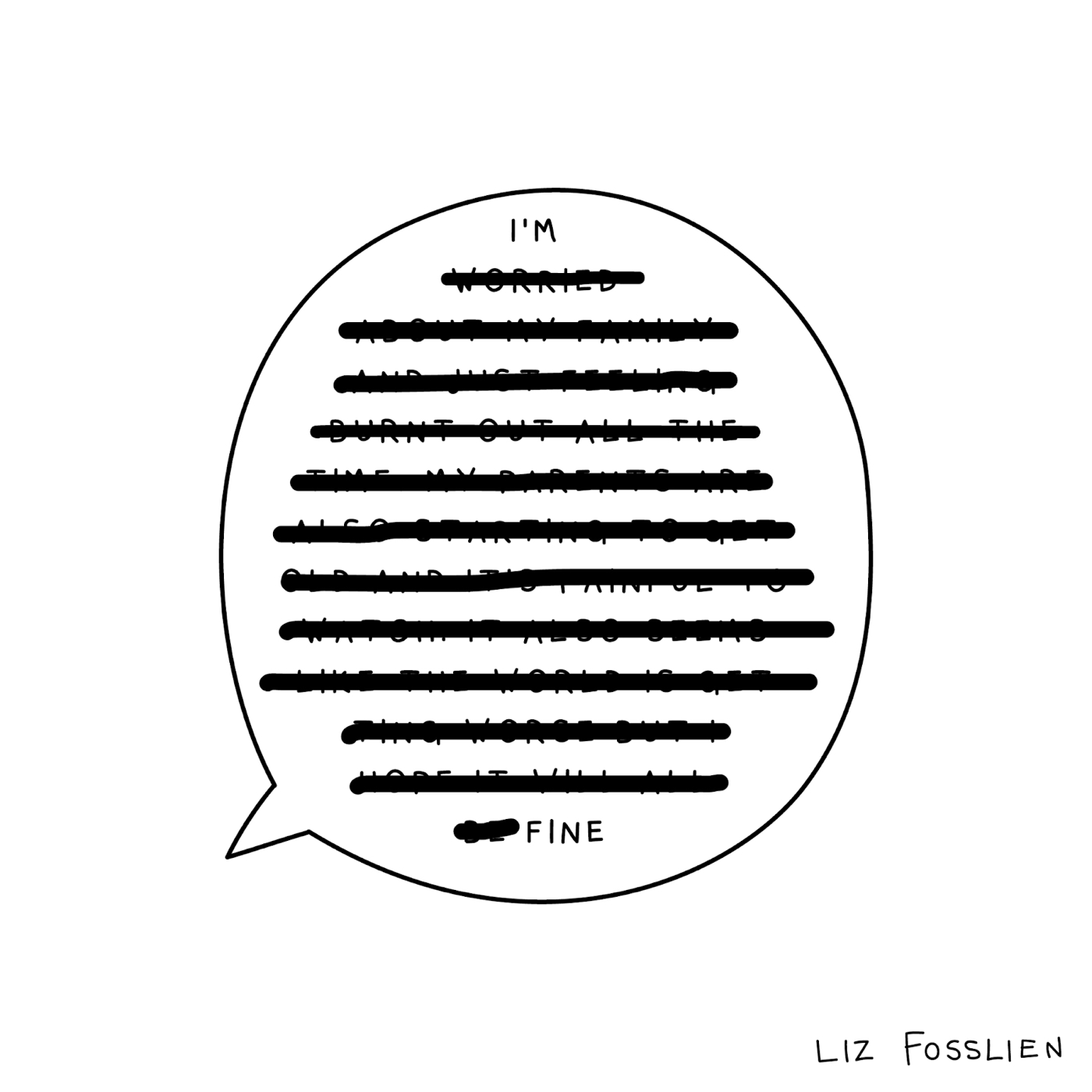

I had been writing articles and I asked Liz to illustrate some of them. Liz is able to visualize things that can be difficult to verbalize—which happens a lot when you’re writing about emotions. She’s able to take something in words and turn it into something visual that speaks to exactly what we’re trying to get across.

One of the articles we wrote for Susan Cain’s Quiet Rev platform went viral: 6 Illustrations That Show What It’s Like in an Introvert’s Head. From that, we got an agent and sold our first book, No Hard Feelings: How To Be Okay When Things Are Not Okay, which came out in 2019 and was a WSJ bestseller.

How They Wrote A Book, Together

Mollie:

People always ask: how do you both write books while having a full-time job? My answer is: “You give your creative hours to the book.” For me, that’s before work in the morning and on the weekends.

Liz:

I’d say my ideal work hours are nine to noon, and five to eight. Kind of the inverse of a traditional work day.

Mollie:

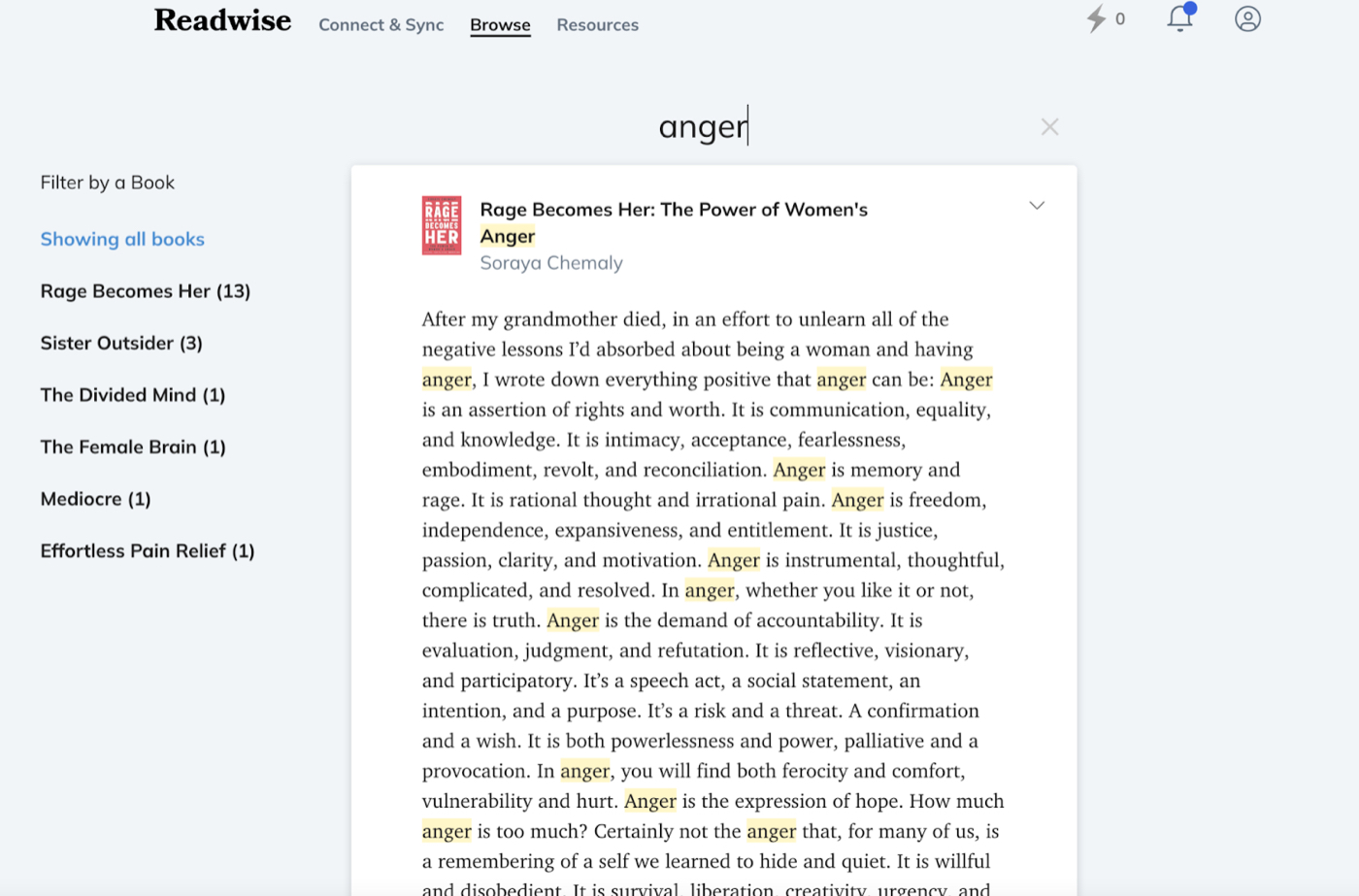

I read a lot and I’m obsessive about taking notes. So for me the process of writing starts with reading. I save a ton of quotes and go back to them later. I read on my Kindle, and all of the highlights end up in Readwise.

Liz:

Mollie is more methodical about keeping notes, tracking sources. And I’m much more chaotic—I’ll scribble something in one notebook one day and in another the next day. My process is much more in my head than in a tool.

Early on, all of Mollie’s organization felt unnecessary. But eventually I grew to appreciate it.

Mollie:

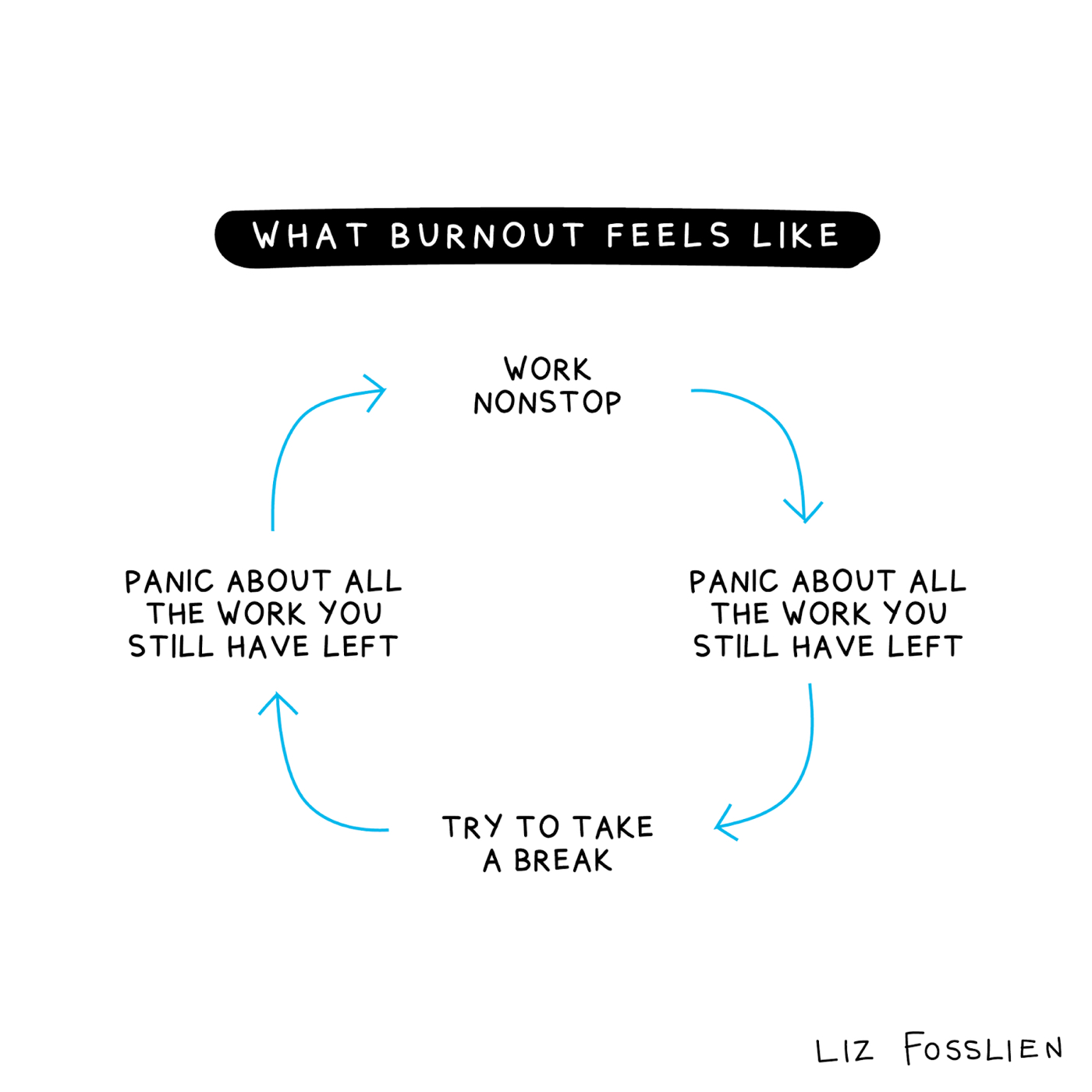

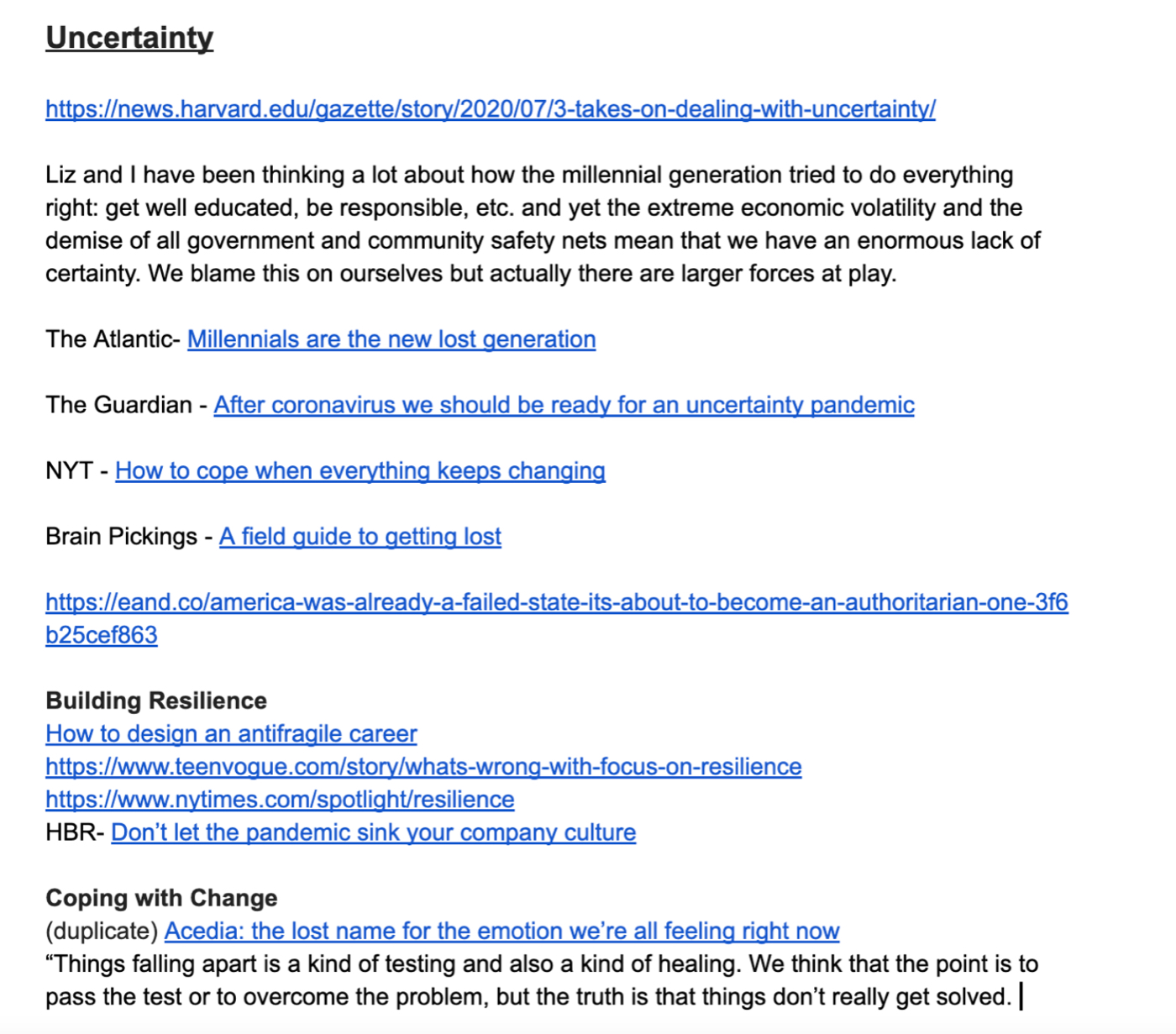

We start our writing process by writing a list of all of the topics we want to cover. For Big Feelings, that was anger, burnout, regret, uncertainty, etc. Then I start reading broadly in all of those areas, highlighting stuff along the way. As we start writing a more detailed outline, I go back through Readwise and search for interesting quotes and ideas on each topic.

A screenshot from Mollie’s Readwise account, where she’s searching for quotes about anger.Next, we create a massive research document in a Google Doc where we dump in anything interesting we find, organized by topic. We put in quotes, people to interview, stories, illustration ideas—all of the stuff that we’d need when we actually go in to write the chapter.

A screenshot of Liz and Mollie’s research outline

Once we have the research document, we create an outline for each chapter. We start by asking: what is the research we want to cover? What are the stories we want to cover? And then one of us starts writing a chapter outline.

At the same time, the other starts writing another chapter outline. Then we switch. We each give comments on the other’s outline, and then the person who wrote the outline writes the first draft of the chapter. We continue switching back and forth on the writing and the editing in each chapter until we send it to our editor for edits.

Liz:

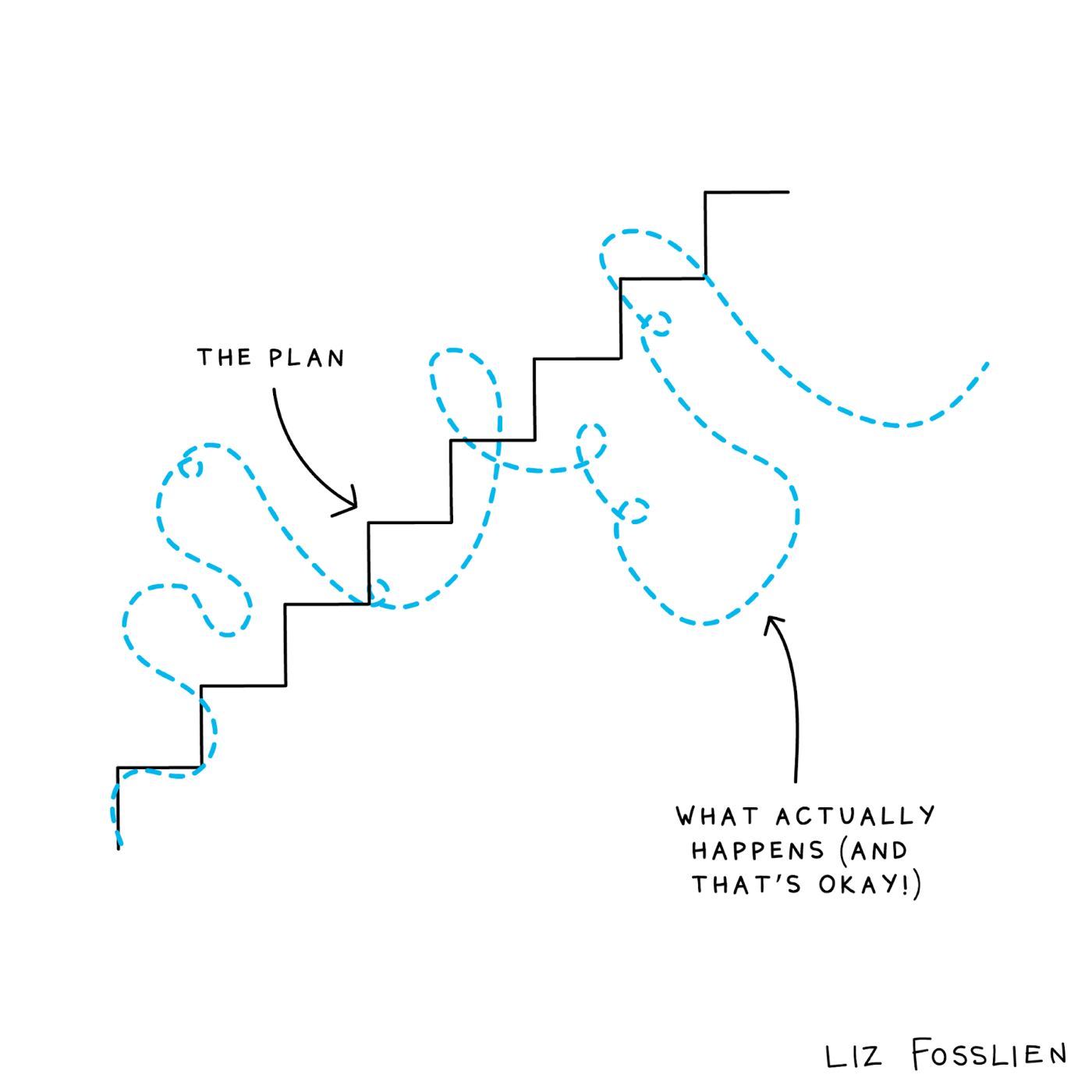

For the illustrations, I always have an unlined notebook to do sketches in. I hate lines and grids.

And then I also have a Pinterest board with all kinds of visuals—Venn Diagrams, bar charts, or an image of Sisyphus pushing a rock up a hill.

On weekend mornings, I’ll usually sit down with an idea I’m working on. I’ll flip through the Pinterest board to find a visual reference that’s going to help bring a specific idea to life.

You can find a detailed breakdown of my illustration process in a video I posted here.

How Their Styles Sometimes Conflict

Mollie:

I am more verbose than Liz in terms of my writing style. The upside of that is that I can sit down and fill an empty page, no problem, which is harder for Liz.

But the downside is, my drafts are long! For our first book, I wrote a draft chapter and it was twice the length that it needed to be. My point of view was, “We’ll send it to the editor who will help us cut it down anyway.” That didn’t sit well with Liz. She said to me, “We need to make this a lot shorter.” That’s hard for me.

Liz:

I’m a bit of a perfectionist about wanting something to be in better shape before we send it to someone else for feedback. I love editing.

My background is in math and economics. So I tend to approach everything from the perspective of: “What does the research say?” And I want to write short, concise tactical tips to move through situations.

Mollie:

And I’m much better at pulling in a quote, or making sure there are interesting stories and narratives.

Sometimes it bothers me when Liz wants to take something and make it way shorter. But on the other hand, I know I can’t do that as well. Liz is really good at concise, clear, actionable writing.

Liz:

I think it takes a bit of self-awareness and a lot of tough conversations to realize that just because your initial reaction is, “This person’s style is so different from mine” it doesn’t mean that’s actually bad.

I remember many moments of staring at a blank page. And being like, “Okay, what should I write? What's the first word that I put on the page?” And struggling with it.

But then the experience of getting a chapter from Mollie that I can reshape helped me realize how much better everything flowed for me if I worked that way. It finally crystallized for me: “Oh, we have these different strengths that work really well together.”

Once I thought about it, I realized, I’m a “lawn mower” that wants to come in and make the grass look very clean. I don’t want to work with another lawn mower. If there’s two lawn mowers we won’t even have a lawn—I need someone who can plant seeds and let them grow so that we’ll have some grass to begin with. That’s what Mollie does.

Mollie:

By the time the book is done, I can’t point to a sentence and say, “That was my sentence.” We trade back and forth so much.

We try really hard to not compare ourselves to each other, and to be generous in our interpretation of what the other person is doing. We want the best for each other, and to give each other opportunities for things.

What Their Emotional Styles Are Like

Liz:

I have a lot of emotions. I can be euphoric in one moment and depressed the next.

My parents are both academics, they’re immigrants, they’re extremely stoic and I am an only child. I grew up in an environment where big expressions of emotion rarely happened. When it did, it was scary. So coming from that environment created a perfectionistic attitude in me about my tendency to have big emotions.

Mollie:

I am very interested in emotions, but I’m more of an underemoter (take our emotional expression tendency assessment here to find out if you’re and under, even, or overemoter). I can talk through emotions in a calm way, and I’m receptive to them, but I don’t express them as much as others.

Overemoters get really excited about things, they have big emotions, and you can easily read their emotions. Underemoters are a little harder to read.

My parents got divorced when I was nine and it was a difficult process. As hard as it was, I think it gave me a sixth sense for what other people are feeling, reading a room, being able to be a peacemaker, and navigating through difficult conversations.

Liz:

I often try to suppress the parts of myself that feel big emotions.

I always felt like I had to have two versions of myself. One was the real me who’s a mess who’s eating Cheez Whiz out of a can, and the other was the polished version of me that I felt like I had to show in order to be loved.

It took a lot of therapy for me to figure out how to open up about the unpolished side of myself to people I am close to.

Mollie:

I love Liz’s unpolished side!

The downside of my style is that it can be hard for me to know what my own emotional needs are and to act on them. I generally pay more attention to what other people are feeling.

We talk about this in Big Feelings: when you’re more in tune with what everyone else needs than what you yourself need, it can be exhausting and can lead to burnout.

Tactics to Stay Friends

Mollie:

When we were writing our first book, we abruptly went from a friendship to a professional relationship. We had to learn to check in on a personal level more often.

Liz:

I remember at one point my husband asked me something about Mollie’s personal life, and I had no idea what the answer was. At the time we were talking every day. It was wild how easily that stuff slips off the agenda, because we both like to focus and hit goals.

Personal check-ins build goodwill and appreciation for each other, which help when you’re running into differences.

Sometimes we do a personal check in at the beginning of a work call, and sometimes we put an hour on the calendar to take more time.

Mollie:

The other thing we do is have tough conversations regularly.

We have to deal with money issues, including how to divide up our book advance payments. And we also have to deal with the logistics of working together, like systems for file management, or responding to email.

In the beginning, resentment would build up because we hadn’t been talking about the small frustrations. But we realized that even if it’s a small issue, we want the other person to bring it up sooner rather than later. We have trust now that when the other person says, “Can you please stop responding to emails like that,” it comes from a place of preventing resentment.

If you’re interested in more from Liz and Mollie I highly recommend you check out their new book Big Feelings. I read it in preparation for this interview, and it was really good.

They do an excellent job of weaving personal stories, together with the latest research and tactical advice for understanding and dealing with emotions like burnout, uncertainty, despair and anger.

Find Out What

Comes Next in Tech.

Start your free trial.

New ideas to help you build the future—in your inbox, every day. Trusted by over 75,000 readers.

SubscribeAlready have an account? Sign in

What's included?

-

Unlimited access to our daily essays by Dan Shipper, Evan Armstrong, and a roster of the best tech writers on the internet

-

Full access to an archive of hundreds of in-depth articles

-

-

Priority access and subscriber-only discounts to courses, events, and more

-

Ad-free experience

-

Access to our Discord community

Thanks to our Sponsor: Mem

Forget about folders and hierarchies for organization and unlock a self-organizing workspace with the help of AI. Get all your notes, documents, content, and e-mails in context with Mem.

Comments

Don't have an account? Sign up!