Why Are Republicans Better at Making Money on the Internet?

What consumer tech and media got wrong

May 11, 2023

Sponsored By: Brave

Let's get real: the internet can feel creepy sometimes. That's where Brave Browser comes in – your new privacy pal.

There have been three great beneficiaries of the attention economy. First and second were Facebook and Google, both of which have built some of the most incredible businesses of all time. Weirdly, many other consumer brands playing in the same arena have struggled. Just in the past few months, Vice, Gawker, BuzzFeed, IRL, BeReal, and Clubhouse have all struggled to capture some of that sweet eyeball-associated revenue.

Even more interesting is the third group of beneficiaries: Right-wing publications have thrived.

The Daily Wire, Ben Shapiro’s Nashville-based outfit, has over 1M paying subscribers, and is estimated to have pulled in over $200M in revenue in 2022. Alex Jones, the conspiracy theorist who said that the elementary school shooting in Sandy Hook was a hoax, pulled in $165M over three years selling supplements. And there are many others! The Drudge Report is a one-man money-making machine. Rumble has emerged as a legitimate competitor to YouTube with real revenue/users. Depending on your bent, Twitter may even qualify as one of these companies now too.

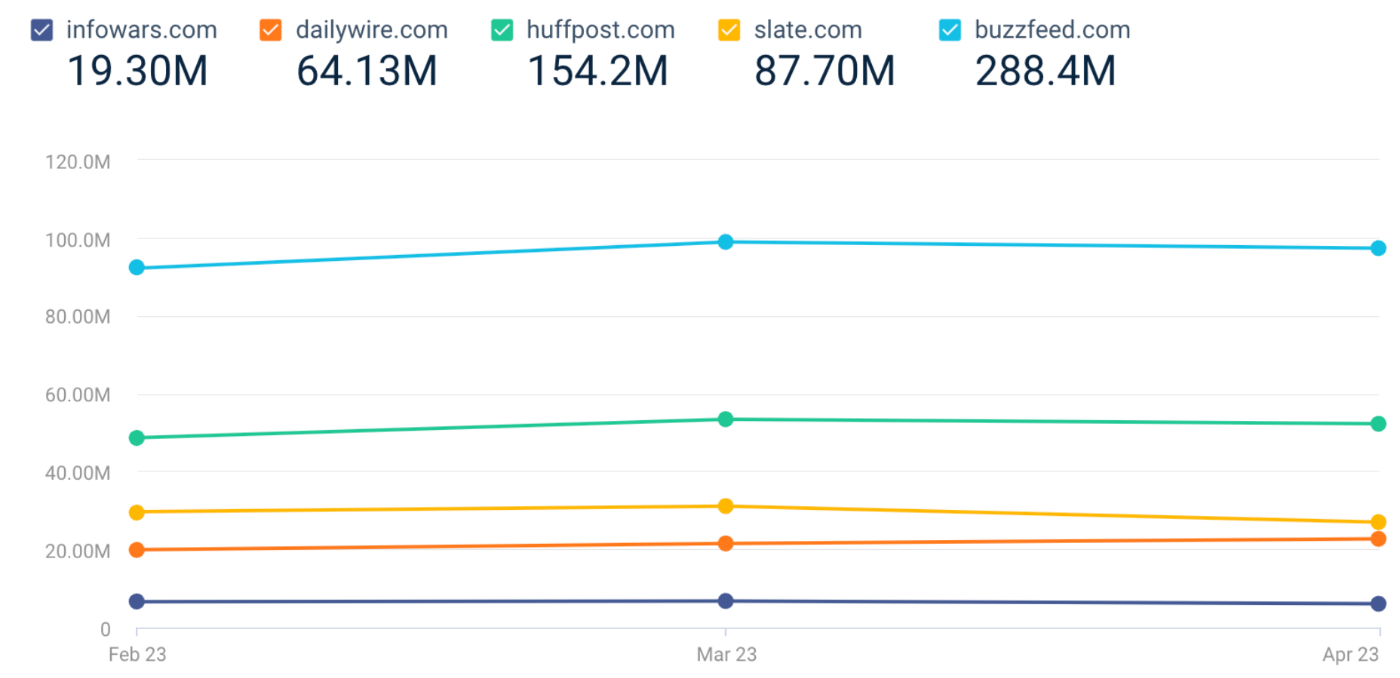

What matters is that, from a business perspective, these businesses have succeeded while utilizing the same playbook. They had similar technology. They had similar tools. They even have somewhat similar traffic:

But they have had wildly different outcomes. Despite BuzzFeed (which also owns huffpost.com) having nearly 6x the traffic, Daily Wire makes 50% of BuzzFeed’s revenue. So what happened?

The title of this piece is tongue-in-cheek but it is also kind of real. Why have right-wing publications thrived? The left-leaning publications had Ivy League–educated employees and the best investors in the world, but they haven’t lived up to expectations.

This contrast is especially bizarre because both sides are children of the same media scene. Early 2000s New York was the birthplace of seemingly everyone in digital media. Andrew Breitbart was a co-founder of the Huffington Post. Steve Bannon hung around the BuzzFeed team. Vice co-founder Gavin McInnes helped start the Proud Boys. Chris Poole, the founder of 4chan, was a loose affiliate of the New York digital media scene, too. Ben Shapiro was Andrew Breitbart’s intern.

Sick of being followed by ads? Want faster browsing without compromising on privacy? Brave can do it all - ad-blocking, even on YouTube, private search, and more in just one nifty app. Plus, it plays nice with your favorite extensions!

Brave is faster than Chrome, more hush-hush than Safari, and available on Android, iOS, and desktop. No more annoying cookie requests or sneaky trackers. And guess what? That means better battery life and mobile data savings!

The answer matters not just for media participants but for everyone whose business has a digital component. At various levels of abstraction, every business on the planet is in the game of driving website traffic and converting that traffic into money. Understanding how Alex Jones has a better business than BuzzFeed matters.

The BuzzFeed bet

On August 11, 2014, Chris Dixon and a16z announced they were leading a $50M round into BuzzFeed at an $850M valuation. In a blog post on his personal website, which he has now deleted (lol), Dixon explained the thesis for the bet:

“Many of today’s great media companies were built on top of emerging technologies. Examples include Time Inc., which was built on color printing, CBS, which was built on radio, and Viacom, which was built on cable TV. We’re presently in the midst of a major technological shift in which, increasingly, news and entertainment are being distributed on social networks and consumed on mobile devices. We believe BuzzFeed will emerge from this period as a preeminent media company.”

Honestly, this feels reasonable. Chris, there was no need to delete the post! Venture capital is a game where 1/20 bets pays off. At the time when they deployed this capital, it really seemed like a smart risk/reward ratio. I talked with Ben Smith—the editor in chief at Semafor, the former EIC at BuzzFeed News, and the author of the new book Traffic—who described to me what it felt like in the years between 2012 and 2015. If you pay attention, you’ll notice the fundamental error they made in their assumptions:

“We had this core thesis that social media was swallowing media. We were going to be the big, big content media company built into the social media ecosystem. We were profitable. Our revenue was growing fast. Our cultural cache and brand were growing fast too.”

Didn’t catch it? Let me give you another hint from Dixon:

“We see BuzzFeed as a prime example of what we call a ‘full-stack startup.’ BuzzFeed is a media company in the same sense that Tesla is a car company, Uber is a taxi company, or Netflix is a streaming movie company. We believe we’re in the ‘deployment’ phase of the internet. The foundation has been laid. Tech is now spreading through every industry and every part of the world. The most interesting tech companies aren’t trying to sell software to other companies. They are trying to reshape industries from top to bottom.”

BuzzFeed was not a full-stack startup. It was not even a 30% startup. It was simultaneously outsourcing its most important competitive advantage (distribution) to the exact same company they were competing for revenue with (ad dollars).

The team had a misguided faith that Facebook would treat them right. This feeling wasn’t without justification—Zuckerberg tried to buy BuzzFeed at one point, and BuzzFeed founder and CEO Jonah Peretti had the ear of the Newsfeed product managers. Their relationship was so strong that at one point, Peretti got the Facebook team to kill the title format a competitor named UpStart was using to kick BuzzFeed’s ass.

This state of growth was never going to last. Facebook started cutting BuzzFeed’s traffic off, and even around the time of the a16z deal there were warning signs. Smith explained to me:

“The 2012–2015 period is when we thought we had the wind at our back. There were little pings of things that were starting to make us a little nervous for the ad business. In particular, the scale wasn’t turning into money the way it should have.”

It turned out that social media wasn’t a new distributor—it was a new competitor. User-generated content was free, and distribution platforms captured all of the value associated with it. So how did right-wing publications escape this trap?

Virality distribution curves

Before we talk about Alex Jones, we need to lay down some digital monetization theory.

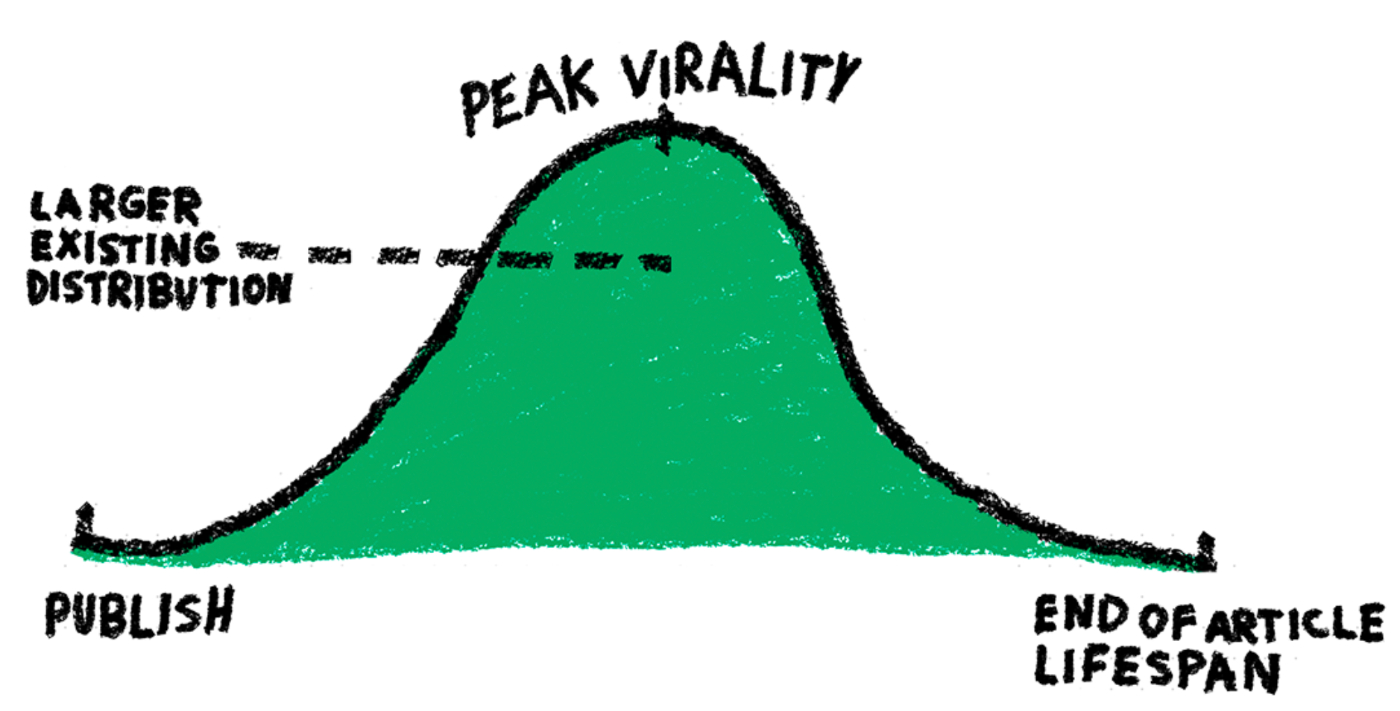

Every time a web page is published online, its lifecycle goes something like this:

This isn’t just for content companies—SaaS startups, ecommerce websites, it is all the same game of digital distribution. Every webpage you publish, every article you release, is fighting for someone’s eyeball in the browser. Existing publishers are able to outperform new entrants because their existing distribution mechanisms (customer accounts, followers on social platforms, etc.) help increase their virality coefficient.

Once a webpage is browsed there are only three options to monetize:

To make money online, that’s all there is to it. To get rich, you maximize the most relevant variables in this equation.

Right-wing publications have thrived because they didn’t make the fundamental error of being reliant on social for distribution and on ads for monetization.

To the right

Right around 2016, when BuzzFeed’s prospects started to turn negative, conservatives began to accuse Facebook of censoring their views. Again, you could choose whether or not to believe that was true. But what matters is that all of the conservative publications acted like it was. They built this knee-jerk reaction to always funnel people back toward their own websites. They would counter-position their brands as “anti-woke” and “against censorship.” In doing so, they would encourage users to pull out credit cards or input email addresses in order to get access to their version of the truth without Facebook’s interference.

This wasn’t even close to reality. It turns out that conservative content way, way outperformed liberal content on Facebook. In Traffic, Smith wrote:

“Facebook’s research contained a curious detail, one of the company’s own analysts confided…relatively small right-wing websites seemed to be getting far more ‘engagement’ by Facebook’s metrics than huge liberal ones, like Upworth, or The Huffington Post, or BuzzFeed.”

Other work by journalists backed up that finding: conservative outlets consistently outperformed other publications through some combination of audience engagement and encouragement by Facebook’s recommender system. Simultaneously, because so many mainstream advertisers didn’t want to be associated with hyper-political content, conservative outlets got significantly better at non-ad-based monetization. Even organizations like the Proud Boys learned it could make money through T-shirt sales.

Conservative outlets, through dumb luck or cunning wisdom, found themselves perfectly counter-positioned, unfairly distributed, and robustly monetized. Liberal digital media startups, like Slate or BuzzFeed, learned these lessons too late. Ironically, Smith’s book has a whole chapter devoted to the New York Times, which learned the value of paywalls, e-commerce, and additional SKU offerings earlier than everyone else and has thrived because of it.

Again, it is easy to dunk on these entrepreneurs, who made the mistake of maximizing traffic. Rather than focusing on growth funnels/loops, these companies made a reasonable, understandable bet that didn’t play out. The conservative outlets didn’t succeed because of capability, they won because life dealt them an incredible hand.

Some notes on failure and lessons learned

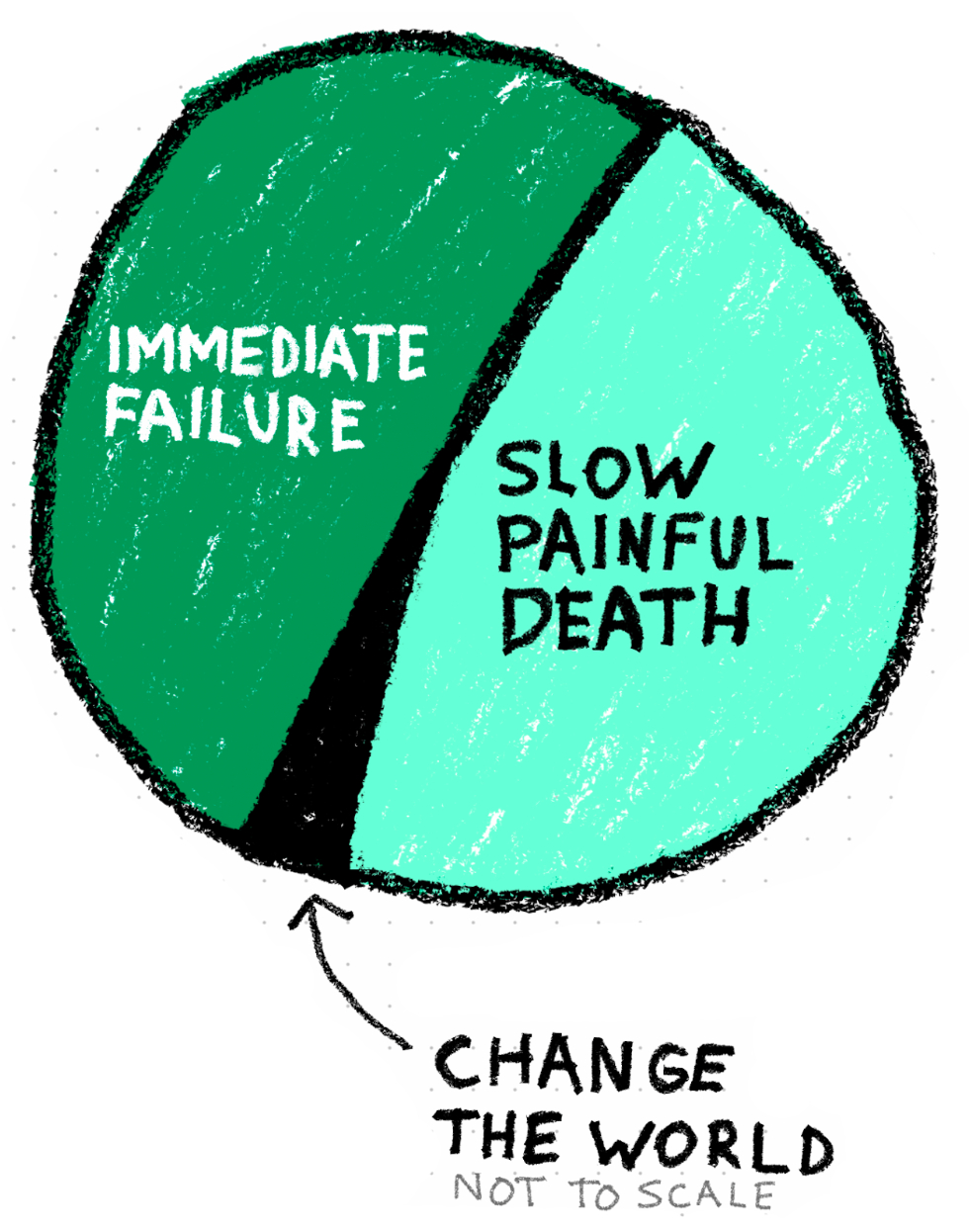

A startup is an infinite variable machine where almost every path leads to obsolescence. There are just so many ways that a founder’s dream can die a miserable death. If you were to plot out the chances a startup has at becoming a world-changing company, it would look something like this:

That any companies make it at all is tantamount to a miracle bestowed from on high by Capitalist Jesus. In this regard, I’ve always had a strong distaste for those false prophets who dunk on startups for making “obvious mistakes.” If launching a startup was a clear win, a Harvard MBA would do it (and probably fail at it). The truly great stuff is complicated and counterintuitive and sorta stupid-sounding until, all at once, it works.

The majority of you are tech and finance people—so it would be fair to wonder why I’ve been devoting so much research toward media companies over the past few months. These businesses are perfect case studies because they are the purest, fastest expression of what the internet does to every market it touches.

I still believe we are in the early innings of the internet age. By understanding how traffic-oriented companies failed over the past decade, we can learn how to better build all companies in the future. SaaS companies launching their product can use title formatting to boost their viral coefficient. The failures of BuzzFeed News to build a homepage that people want to visit underscores the importance of building a brand and destination people want to return to. Perhaps the biggest lesson is that scale does not equal success. BuzzFeed did $437M in revenue in 2022 but lost $201M.

Famous failures are often great ideas that were too early. Pets.com became Chewy; Webvan became Instacart. Other ideas are good attempts but just don’t work. Theranos is a good idea (if you can get the science to work). WeWork is a great business (if you can get the economics to function). Sometimes the timing isn’t right or the team makes operational mistakes, but when a startup fails it is net-on-net a good thing—it means we are funding big swings at changing the world. Even if all these publications were to end up being gone in the next few years, we should give credit to the teams for trying.

Publisher’s note: When I sat down on Monday, this piece was supposed to be a book review. It ended up going in a very different direction (lol). But I really appreciated Ben Smith’s time and very much enjoyed his book. Reading his book and examining these publishers made me feel like an orphan discovering his own family history. I fell completely ass-backwards into being a writer/online publisher. I didn’t study these businesses when I got started. I just had a lot of opinions and farted them out onto the internet and remarkably that started to pay my bills. I think, like Shapiro before me, I ended up doing well online through circumstance, not through foresight. If you care about media, startups, or the future of the internet, it is an incredible read and you should buy it.

Find Out What

Comes Next in Tech.

Start your free trial.

New ideas to help you build the future—in your inbox, every day. Trusted by over 75,000 readers.

SubscribeAlready have an account? Sign in

What's included?

-

Unlimited access to our daily essays by Dan Shipper, Evan Armstrong, and a roster of the best tech writers on the internet

-

Full access to an archive of hundreds of in-depth articles

-

-

Priority access and subscriber-only discounts to courses, events, and more

-

Ad-free experience

-

Access to our Discord community

Thanks to our Sponsor: Brave

Thanks again to today's sponsor, Brave, the privacy-focused browser that makes the internet ad-free. It's faster than Chrome, more hush-hush than Safari, and available on Android, iOS, and desktop.

Comments

Don't have an account? Sign up!