The yassification of killing robots makes me queasy.

Last week, Anduril, a prominent defense technology startup valued at $8.5B, announced that it had acquired the “Fury” line of autonomous airplanes. Think of the plane as a Roomba that can fly, substituting its vacuum for missiles. While the product is not yet deployed, the acquisition was clearly done with the hope of selling these machines by the hundreds.

In my naivety, I expected the tech community to have some reservations. After all, these planes are powered by an AI technology whose sole purpose is slaughter.

Instead, X was full of comments showering the announcement with adoration. A sampling of real tweets:

“This makes me so horny”

“*laughs in American asymmetric advantage*”

“This is beautiful. I love the military industrial complex so much.”

I do not want to paint with a broad brush. The dialogue around Silicon Valley’s relationship with the military almost always devolves into tribal warfare, with little space for nuance. My family has a history of military service, and my father-in-law was in the Air Force. Additionally, I’ve argued for years about the power of technology to pull society forward. Ultimately, I feel that war and the technology that supports it are sometimes necessary, but always complicated.

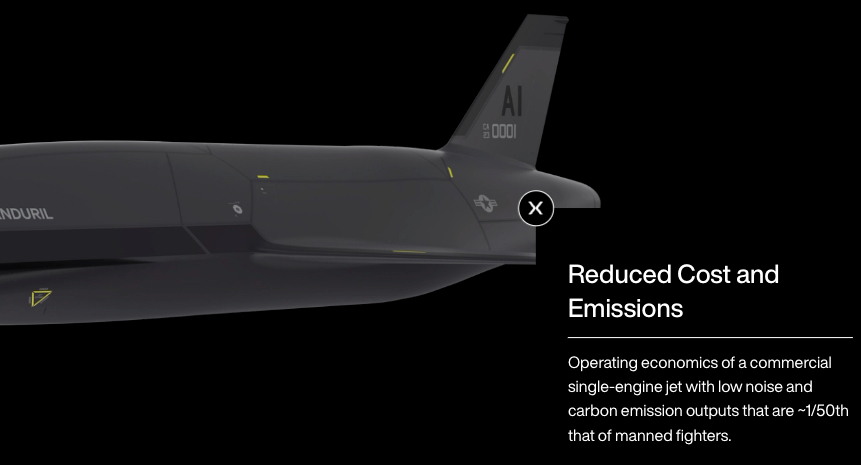

The hyperbole starts with the marketing: the Fury aircraft launch could’ve been ripped from the latest iPhone event. The landing page brags about “reduced emissions.” There is a slick YouTube video with sensual, slow-mo shots of the product. Brand advocates hyped up the product to their followers. For anyone who has read a software marketing blog or two, it was clear that Anduril was following a playbook that is battle-tested in Silicon Valley.

Image source: Fury launch page

Beyond Anduril, there appears to be a cognitive dissonance about what the defense sector does. Defense tech isn’t building weapons designed to more efficiently kill people—it is supporting “American Dynamism.” Venture capitalists who engage in lobbying aren’t throwing parties for the military-industrial complex; they’re “one of the leading voices” who just so happen to have hundreds of millions in capital. I personally have received outreach from multiple funds asking for help spinning up content around why they are good partners for defense technology companies. Everyone wants a piece of the murder money pie.

Let me be clear: it’s morally bankrupt to view defense as an exciting market. This sector is not bald eagles and Abraham Lincoln riding a grizzly bear. It is death and pain and blood soaking into the mud. Defense technology should be a sober, honest affair. Instead, some in Silicon Valley view it as a vaguely nationalistic way to make billions of dollars.

To be fair, our industry was birthed in partnership with the military. The first true Silicon Valley startup, Fairchild Semiconductor, had some of its chips used in defense applications after its incorporation in 1957. The very first Silicon Valley IPO in 1956, Varian Associates, sold microwave tubes for military applications. It is fair to say that without the U.S. government’s purchasing power, much of the technological progress we currently enjoy would not have happened or would have been much delayed.

To the outside observer, it may appear to be easier for these companies to do their work quietly. It raises the question: why bother to do this type of marketing?

The scarcest of resources

Ultimately, players in the defense ecosystem like Anduril are engaging in this type of chest-thumping promotion to get the two most important resources in Silicon Valley: dollars and engineers.

Dollars: For many years, startups have been doing the “consumerization of the enterprise,” where B2B products are expected to have consumer product-level experiences. Anduril and its like are applying that principle from B2B SaaS to machine guns. And by all accounts, this works. Both investors and customers are clamoring for what they are selling.

Anduril rode high to a multi-billion-dollar valuation. I know of multiple other startups whose rounds have not yet been publicly announced that are building similar technologies combining AI and defense. The defense department has publicly discussed its desire to build an entire fleet of AI vehicles with which to fight China.

Engineers: The challenge of Silicon Valley is that any incredible engineer could relatively easily earn more than $500,000 at a Big Tech company. A founder’s challenge is to convince them to join a startup that will pay them a third as much to work twice as hard. Since pesky, handsome bloggers keep doing the Napkin Math™ on why working at a startup is a bad financial choice, founders are stuck recruiting folks with either the company’s mission or the technical challenge. Cue the diatribes of patriotism and the emphasis on cutting-edge technology. Scared by what Russia did in Ukraine? Come work with us. Want to do something more interesting than optimizing ad sales buttons? Build a flamethrower.

Look, I know the world is a dangerous place. Peace is earned, not given. Technologists have a role to play in equipping democracies with the inventions that allow them to protect their national interests. I’m not a political theorist and do not pretend to be qualified enough to debate the nuances, but I recognize the broad necessity of this sector.

But building a cult of personality around certain founders, stoking the fires of nationalism, and then sprinkling in AI death machines is not the way the technology industry should conduct itself. It feels crazy to have to say that, but here we are.

The irony is that inside many of these companies, people are more sober about what they do. Most teams are some pairing of technical staff and “operators,” which is a euphemism for people with frontline experience. It is not fun and games when soldiers' lives depend on your code working, and the teams are generally constructed in recognition of that fact. However, the external-facing components of these companies, the investors who support them, and the ardent fans online seem to treat this as just another market for VC dollars to conquer.

To understand why this is happening, it is worth diving into the history of overreliance on hyperbole in defense tech.

It all started with Palantir, a public company co-founded by Peter Thiel that has a ~$33B valuation. The company, which does data analytics for three-letter agencies like the CIA, was deeply secretive, by nature of its work with clients, and allowed claims of its capabilities to gradually build unchallenged.

It culminated with numerous media reports speculating that the company’s products had been key in the location and killing of Osama Bin Laden. According to three of my sources who were at the company at the time, this claim is false, but it was a fortuitous rumor that the Palantir PR team did nothing to dissuade. It was woven into the mythology of Palantir and is still brought up in coverage. This narrative helped the company significantly increase its book of business.

To my mind, the world of defense tech in Silicon Valley learned a valuable lesson: hype earns revenue.

Lord of the Errors

It’s no coincidence that both Anduril and Palantir took their names from The Lord of the Rings by J.R.R. Tolkien.

The novel is beloved by many in tech, myself included (I visited Tolkien’s favorite pubs in Oxford this summer and will tour Hobbiton in New Zealand in 14 weeks and two days…but who’s counting). And I know this is a small, nerdy thing, but both of these companies are completely misunderstanding the point of the books.

Tolkien fought in World War I and was at the Battle of the Somme, a skirmish that lasted for five months and saw over 1 million soldiers killed. WWI was a war of massive technological change. At the Somme, the British deployed tanks for the first time. Artillery shells fell by the hundreds. Chemical weapons filled the lungs of soldiers and flamethrowers burned people alive. It was a horrible, ghastly thing, and Tolkien witnessed how cruel man can be.

In LOTR, the enemy is industrialization. Trees are the good guys. The villains housed in Mordor and Isengard build machines of metal to destroy the world of men. Good triumphs not by having the shiniest new weapon, but by the power of friendship and the decency of the small people in the world.

Tolkien even writes a speech arguing against weapon worship! Here is the character Faramir:

“War must be, while we defend our lives against a destroyer who would devour all; but I do not love the bright sword for its sharpness, nor the arrow for its swiftness, nor the warrior for his glory. I love only that which they defend.” [emphasis added]

In LOTR, the heroes are not bombastic loudmouths, seeking glory and praise. Instead, they are emotional, feeling men, who think hard about the consequences of their actions. When Sam Gamgee witnessed the aftermath of a battle, “He wondered what the man’s name was and where he came from; and if he was really evil of heart, or what lies or threats had led him on the long march from his home; and if he would not really rather have stayed there in peace. . .” To me it is hard not to hear echoes of Tolkien's time at the Somme. When Boromir died protecting the Hobbits, Aragon “knelt for a while, bent with weeping, still clasping Boromir’s hand.”

It is difficult to square the gentle, valiant language of Tolkien’s world and the community these companies have cultivated.

Perhaps most hilariously, the companies’ literal names are being used incorrectly. A palantir is a device that allows the user to view events anywhere in the world. On the surface, this is a clever use, because Palantir, the company, allows governments to do the same. However, in the Third Age (the time period in which the books/films take place), using a palantir corrupts the soul! You become a bad guy when you use it. Anduril is named after a sword—the translation is “flame of the west”—which is ironic when Faramir’s speech clearly calls out selling how shiny your sword is.

The complicated truth

Two things can be simultaneously true: Western democracy may need to radically improve its defense technology while the way we currently talk about this change is gross.

The hype-driven marketing of defense technology raises real concerns. By portraying weapons as next-gen products, these companies risk dulling our sensitivity to the human costs of conflict. Their focus on financial success over emotional prudence could lead to short-sighted development and deployment of technologies we may come to regret. As technologists, we must acknowledge our role in armed forces, but not be complacent about the effects of our work.

Before accepting lucrative contracts or prestigious challenges, we should reflect on how our innovations could impact life on the battlefield and beyond. As citizens, we must demand transparency from these companies and scrutinize expansions in military AI. The stakes are too high to leave such matters to profit motives alone.

Find Out What

Comes Next in Tech.

Start your free trial.

New ideas to help you build the future—in your inbox, every day. Trusted by over 75,000 readers.

SubscribeAlready have an account? Sign in

What's included?

-

Unlimited access to our daily essays by Dan Shipper, Evan Armstrong, and a roster of the best tech writers on the internet

-

Full access to an archive of hundreds of in-depth articles

-

-

Priority access and subscriber-only discounts to courses, events, and more

-

Ad-free experience

-

Access to our Discord community

Comments

Don't have an account? Sign up!

Definitely guilty of this myself, looking at now and the past. Military engineering can be so fascinating and excellent (existential threats will do that) that it's hard not to get excited and damn near giddy when I look at a beautiful weapon. Probably a deflection mechanism in part too, like comedy; don't know how to deal with the true nature of the stakes (and so far removed) that I default to some mix of "OMG beautiful engineering" analytical and "big explosion boom fast jet zoom" caveman mind that really tickles my fancy. I have decent appreciation and respect for war (obviously nowhere near somebody who's directly or closely felt the impact), yet I have trouble squaring my excitement for weapons with hatred of destruction.

One aspect left out from the article which I believe to be especially true now (though has also been thought and proved wrong countless times in the past) is that this new breed of technologically advanced weapons remove people and increase accuracy, and therefore may be saving lives relatively (though yes, they thought dynamite, machine guns, and bombers would save lives too). Alas maybe drones would just mean we can create more weapons than ever before and destruction will only increase, but whereas those previous examples only increased scale with little change to decision-making, accuracy, or human risk, these increase scale while improving all of those significantly. The dream of the Bomber Mafia may finally be coming to fruition. Further, companies like Anduril are challenging the entire military-industrial complex system, which costs hundreds of billions a year in inefficiencies.

I think most people even drawn to these companies don't have it lost on them what their work truly means. I imagine they've thought about it extensively and had existential crises on the matter. Through the lens of "transforming war from a battle of humans to robots and disrupting one of the most corrupt, damaging institutions in America" I believe excitement and damn near glee is warranted.