I have a pretty idiosyncratic book notes system. I learned it from my high school English teacher about 10 years ago.

She introduced me to this system, and to a bunch of books that have stuck with me all these years. But she and I didn’t start out well.

She was demanding, and I was unfocused and determined to skate by while doing the minimum amount of work. English class had always been pretty easy for me, and so at the beginning of the semester I consistently showed up unprepared — having slapped together the homework at the last minute, or having skipped the reading but confident I could pretend to pontificate about it anyway.

To her this was unacceptable — she was tough, and her rage was volcanic. The little details mattered to her. It was imperative to read closely, and deeply, and to understand both the logical structure and the deeper meaning of the books we were reading. There was no skating by in her class.

Some students decided to tune her out. But, for some reason, I decided to do the opposite: whatever she expected, I would try to match or exceed it.

I don’t know exactly why I decided to do this. I think at some base level, I sensed that she had a point. That maybe she wasn’t arbitrarily demanding. She was demanding because she wanted us to get it: to read books, and to feel them, and to understand them. And that made it worth the extra work.

It turns out she had a very specific system for getting the most out of books. It’s one that she drilled into me in that English class — and I’ve been using it ever since. This is how it goes.

. . .

The directive is simple: to understand a book, it’s best to create a custom index of it.

You’re going to fold up a piece of looseleaf paper two times: once vertically, and once horizontally. Then you’re going to use it to write down each important quote, theme, or idea in the book along with the page number.

When you’re done, you’re going to have a map of the book — and that’s going to help you understand it deeply, and help find things you need later on.

How it works

Every time I start a new book, I also grab a blank sheet of 8.5” by 11” paper. I prefer crisp, white, blank printer paper. But any kind of paper will do.

Then I fold the paper in half hot dog style. By that I mean, I’m trying to make a crease along the vertical axis of the paper like this:

The trick is to line the corners of the paper up so that they’re flush, and hold them together with one hand. When you’re holding paper together like this it’s going to look like a little balloon — edges pressed together, middle bent into an elongated circle.

Once you’re holding things securely this way, set your paper balloon on the table and drag your finger from the edges out towards the fattest part of the balloon to create your crease. As you’re doing this make sure you hold the edges together (they’ll try to squirm away) so that you’ll get as close to make a perfectly centered crease as possible.

Now that you’ve got your crease, repeat the same process to create a horizontal crease, so your paper looks like this:

Once your paper is good and creased, it’s time to fold it up. Fold it first along the horizontal axis, and then the vertical axis so that it forms a little booklet.

Creating a booklet like this is nice because it’s compact, and easy to slip into the book you’re reading as a bookmark — and that’s where it will live for eternity. That makes it easy to find when you pick up the book years later and want to use it for something. It’s also just a nice ritual to do every time you start a book — when I do it, it says to me: “I’m starting. And I’m taking this seriously.”

(Of course, you can skip the above and do this digitally if you read on Kindle — the paper folding is mostly useful for people who read physical books.)

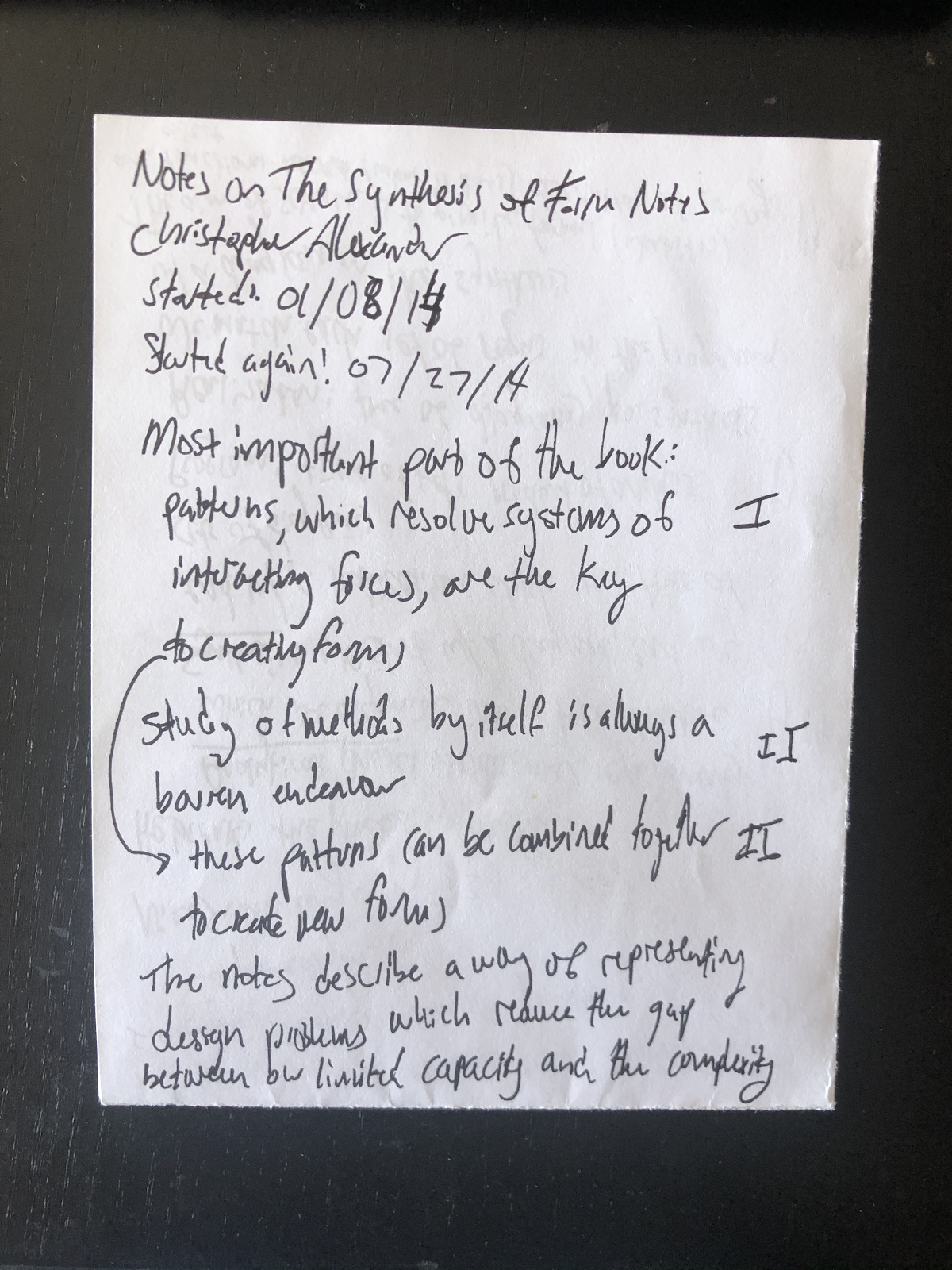

Once I have my little folded up booklet, the first thing I do is I write the title of the book, the author, and when I started reading it. Sometimes I remember to record when I finish it, but not always.

To do this I always use my preferred pen: a black Flair pen by Paper Mate. They’re felt-tipped and their lines are bold and easy to read — it’s kind of like a magic marker squished into pen form. I love them.

When I’ve got my pen in hand, it’s time to read.

As I’m going through the book, I use the booklet to create my index. I’m marking down anything important and the page number it occurred on. These are things like:

- Quotes I like

- Important ideas or concepts

- Key themes

The key is to keep each entry small and self-contained. You just want to put enough so that you’ll remember what it was about — you don’t need every last detail marked in your index.

As I’m going along, I’m also paying attention to things I’ve already recorded. For example, if I come across an idea towards the end of the book that I already found at the beginning, rather than creating a new entry in my index, I’ll go back to my original entry and just add a new page number.

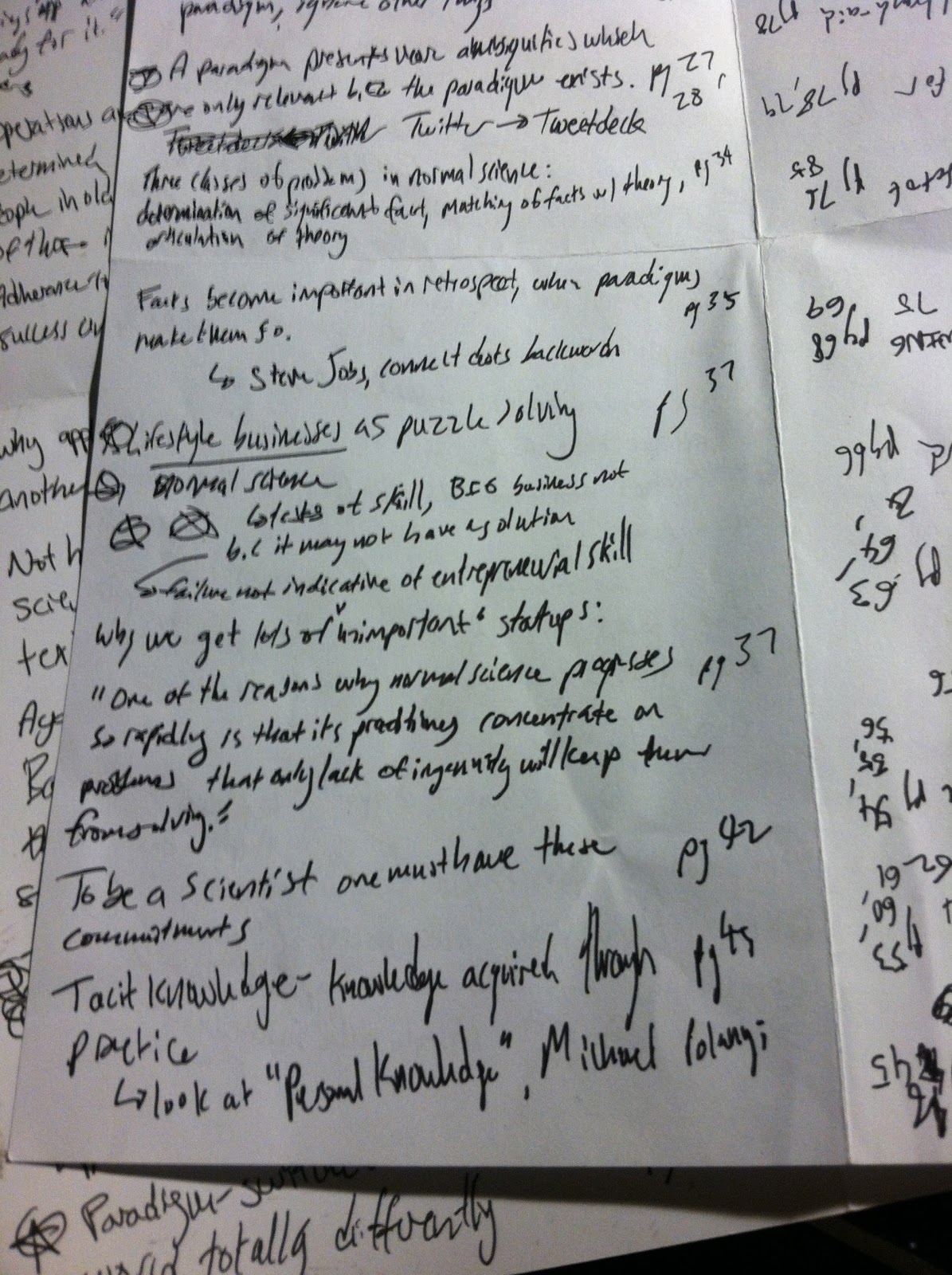

(My index for The Structure of Scientific Revolutions)

Each entry in the index becomes a map that records ideas in every place they occur in the book.

These kinds of indexes are useful for at least two purposes:

- They can help you more deeply understand the structure and argument of the book

- They can help you get to the right nugget much later on when you need it

Use indexes to understand the structure and argument of a book

When you make an index of a book you’re reading you’ll begin to understand what the key ideas are, and how they fit together.

You’ll begin to know how one idea leads to the next, and even be able to see where some of the holes in the argument are.

It’s a little like the difference between listening to an audiobook and having a conversation about the book with the author. When you’re just passively listening you’re often nodding your head even if you don’t really understand. When you’re making an index, you’re actively trying to figure out: is this important? And if it is, where does it fit?

Use indexes to find the right nugget later on

The other advantage of the index is that it’s essentially a scannable map, signposting where all of the important pieces of the book are.

This is really helpful when you’re sitting down to write something and you remember, “Ahh there was this quote from a book I read 5 years ago and I kind of remember it was about 2/3rds of the way through the book on the top part of the left hand page.”

Rather than having to dig through the entire book, you can first consult your index. Usually, if you remember the quote you’ve written it in the index and it’s easy to find. If not, you at least know around where the quote is likely to appear because you know where each topic the book covers is located.

For example, when I sat down to write If your system was a house would you want to live in it? I immediately remembered that the concept I was trying to explain was related to something that Christopher Alexander covered in Notes on the Synthesis of Form.

So I grabbed the book, pulled out my index from 2014 when I read it, and spent about 10 minutes scanning through the most important parts. This let me quickly find the quotes I needed to write the piece.

But...it’s not digital

That’s true, this method isn’t digital.

I like reading paper books — it’s just more enjoyable that way. If I’m reading in an analog way, I find that writing down notes with a pen and paper is fairly intuitive.

The downside is that the notes aren’t searchable and can’t be accessed unless I’m physically with them.

The upside is that as you build your library, every book in your collection has a prize inside. Every time you pick one off the shelf, you’ll have a little gift from past you to present you helping you along.

I’ve tried various methods to digitize these notes: taking pictures and keeping them in Evernote, and transferring them manually into Roam or Notion. I’ve even considered hiring someone to do it for me.

These days I do it as needed — any time I’m using an index to write a piece, I also put the important pieces of it inside of Roam so that I can access them again without having to actually consult the physical book.

I’m working on a more complete solution to this problem though, and I’ll keep you updated on what I find.

A final note on my English teacher

By the end of the semester, I had changed completely. I was focused and working hard and I wasn’t just skating by. I was actually doing extremely well in her class. In fact, I liked being in her class, and I liked her.

I also found a bunch of books that I absolutely fell in love with, and that have stayed with me for life: Pilgrim at Tinker Creek by Annie Dillard (which I wrote about here), Walden by Thoreau, and Desert Solitaire by Edward Abbey.

Some time before the end of our time together she time pulled me aside and told me:

“I’ve got my eye on you. You’re going places. Make sure you use it for good.”

I hope you do the same.

Find Out What

Comes Next in Tech.

Start your free trial.

New ideas to help you build the future—in your inbox, every day. Trusted by over 75,000 readers.

SubscribeAlready have an account? Sign in

What's included?

-

Unlimited access to our daily essays by Dan Shipper, Evan Armstrong, and a roster of the best tech writers on the internet

-

Full access to an archive of hundreds of in-depth articles

-

-

Priority access and subscriber-only discounts to courses, events, and more

-

Ad-free experience

-

Access to our Discord community

Comments

Don't have an account? Sign up!

Great read. Didn't quite grasp the purpose of folding the paper, other than to compact it for storing between pages. Is there more to it?

@hikzero Thank you!! Yup that's the main idea—easy storage in the book