Hey! Nathan here.

I’m thrilled to share this piece with you from behind the paywall of Byrne Hobart’s excellent newsletter, The Diff. Byrne comes from the finance world, but is also a first-rate writer and thinker with serious range. In this piece, he uses two rival 20th century intellectual movements — the “high modernists” and “postmodernists” — to help us better understand the two main investment philosophies most traders adhere to today.

I loved it and I know you will too.

Enjoy!

It’s natural to analyze finance in terms of pairs of tribes. Growth and value, fundamental and technical, quantitative and qualitative, inductive and deductive, bottom-up and top-down. Like all models, they aren’t strictly true, but they are useful. It’s natural to use opposed pairs because finance requires trades, and a trade requires a buyer and a seller who each think they’re getting a good deal—for both sides to be far enough apart that they’re willing to trade, they need different enough worldviews that they can use the same facts to reach different conclusions.

Right now, the most salient dividing line between investors is the high modernists and the postmodernists. High modern investors trade based on gaps between perception and reality; postmodern investors try to profit from the gap between present perception and future perception. The first postmodern investor was probably A. W. Jones, who had the unique curse of a) inventing the modern hedge fund, b) naming it, but c) apparently mumbling when he talked to Carol Loomis—til the day he died, the Harvard/Columbia/US Foreign Service alum insisted that he’d said "hedged fund." Jones’ initial strategy was to pair-trade so he could avoid market volatility: long GE/short Westinghouse, or long Woolworth/short Sears. In some cases, they were betting that one company would perform better than another, but the more common bet was that one company was perceived as being more different from its peers than it really was.

The outside view was that Jones was reducing market and sector risk by picking good stocks; the inside view, at least according to More Money Than God, was that the firm was basically sending kickbacks to sell-side analysts in exchange for getting their best ideas. (This is extremely illegal today, but there has always been a gap between what sell-side analysts ostensibly do, what they can legally do, and what they get paid to do. This gap has substantially narrowed in the last few decades. Today, their function is to broker meetings between company management and institutional investors, and even that going away.)

The beauty of this approach is that it lets a fund concentrate on wherever it has an edge. Market-timing is hard, picking winners and losers within an industry is (comparatively) easy, so if a fund can make the easy part 100% of the variance, it comes out ahead. Correlations within industries are high, so pair-trading reduces a big source of volatility, allowing the fund to lever up. But wait: if industry- and market-level performance explains most of the variance in returns, then long-short funds are spending all of their energy on something relatively unimportant. Which is fine, if it’s important but unknowable. But a focus on relative value constraints the kinds of theories an investor can even entertain. A pair trader can’t spend any time thinking that a particular industry is going to go to zero; they have to focus on incremental differences between firms, not long-term economics.

Postmodern investing is ostensibly atheoretical, but like anyone who claims not to take anything on faith, they ultimately have an unspoken faith-based claim. In this case, it’s the argument that human and institutional irrationality are fundamentally invariant, that you can always expect irrationality to converge. Most of the time, this is a safe bet; market participants systematically overreact to the median news story. But if most investors overreact to news, they underreact when history is being made.

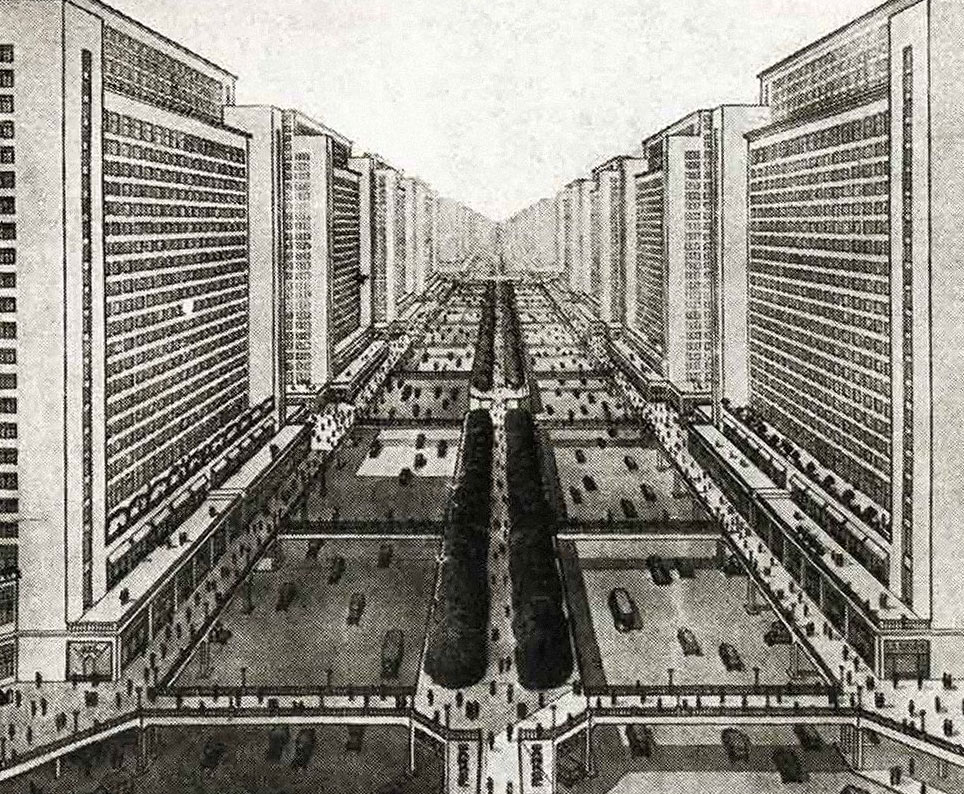

High modernist investors represent a distinct contrast. The original high modernists had a variety of crazy beliefs, but they always believed in something. They built ugly buildings, but these buildings were ugly in a way nobody had imagined before. High Modernist investors are the same way: they have a fundamental thesis, not about the relative merits of two very similar things, but about the absolute merits of a particular view. A high modernist can be 200% long, or all in cash; might have 80% of their portfolio in a single trade, and has a variant view plus a willingness to tolerate fluctuations in the market’s opinion in the meantime. To high modernists, perception is mostly random, but converges on the truth, and that factor dominates any other means of predicting change in perception.

In this sense, both classical value investors like Ben Graham and early macro investors like Soros and Keynes were high modernists. They had a view on how the world was changing, and traded as if everyone would eventually catch on. (In Soros’ case, the theory of reflexivity sounds like a postmodern, truth-is-what-we-believe-it-to-be claim, but in practice Soros used it to master the timing and magnitude of moves, not the underlying change. And in currencies and credit, fundamentals are somewhat reflexive; if everyone decides the Turkish Lira is garbage, that makes it true.)

The postmodernist approach to trading on Coronavirus might be to look at what the CDC said during SARS, H1N1, and Zika, measure how strongly the market reacted to changes in the case count and government action, and try to time the crash/rally on that basis. The High Modernist approach would be closer to a narrative: how bad can it get, who is particularly vulnerable, which countries are taking effective countermeasures, and is it true that the disease only thrives in a narrow temperature/humidity band? Postmodernists thrive when they’re looking at samples close to the mean. But the more extreme the sample, the more likely it is that fundamentals overwhelm sentiment. In extreme market events, the postmodern investor is the last atheist in the foxhole.

Find Out What

Comes Next in Tech.

Start your free trial.

New ideas to help you build the future—in your inbox, every day. Trusted by over 75,000 readers.

SubscribeAlready have an account? Sign in

What's included?

-

Unlimited access to our daily essays by Dan Shipper, Evan Armstrong, and a roster of the best tech writers on the internet

-

Full access to an archive of hundreds of in-depth articles

-

-

Priority access and subscriber-only discounts to courses, events, and more

-

Ad-free experience

-

Access to our Discord community

Comments

Don't have an account? Sign up!