How Physics Explains Business

Physics metaphors are everywhere in business. If you follow where they lead, you end up in fascinating places

January 18, 2023

Business is filled with physics metaphors: Porter’s “five forces,” Helmer’s “seven powers,” startup accelerators, organizational inertia, wedges, leverage, momentum—I could go on.

Businesspeople are attracted to physics jargon because it makes them sound smart. But on a deeper level, it makes the world feel more predictable and in our control. It reminds us that mere mortals have built machines that put men on the moon and bought them safely back to Earth. Surely we can hit our growth targets this quarter—right? 🥲

Some people dislike the use of physics jargon in business. They think the metaphors don’t make sense and only serve to make people seem superficially smart. There is some truth to that, but ultimately, I disagree—physics jargon is cool.

When you exapt a concept from one domain and use it in another—“exaptation” itself being a great example, which I borrowed from evolutionary biology—you’re subtly encouraging people to think about the things that two different systems might have in common. You’re initiating a process where, for each idea you come across, you instinctively contemplate how it might have an analog in a different domain. It’s not just a way to communicate. It’s a way to think.

But if you want to take full advantage of this way of thinking, you need to actually understand what the concepts mean in their original setting. Only then can you benefit from the metaphor. Otherwise it’s just an empty label. You only know the name of the thing, but names don’t constitute knowledge.

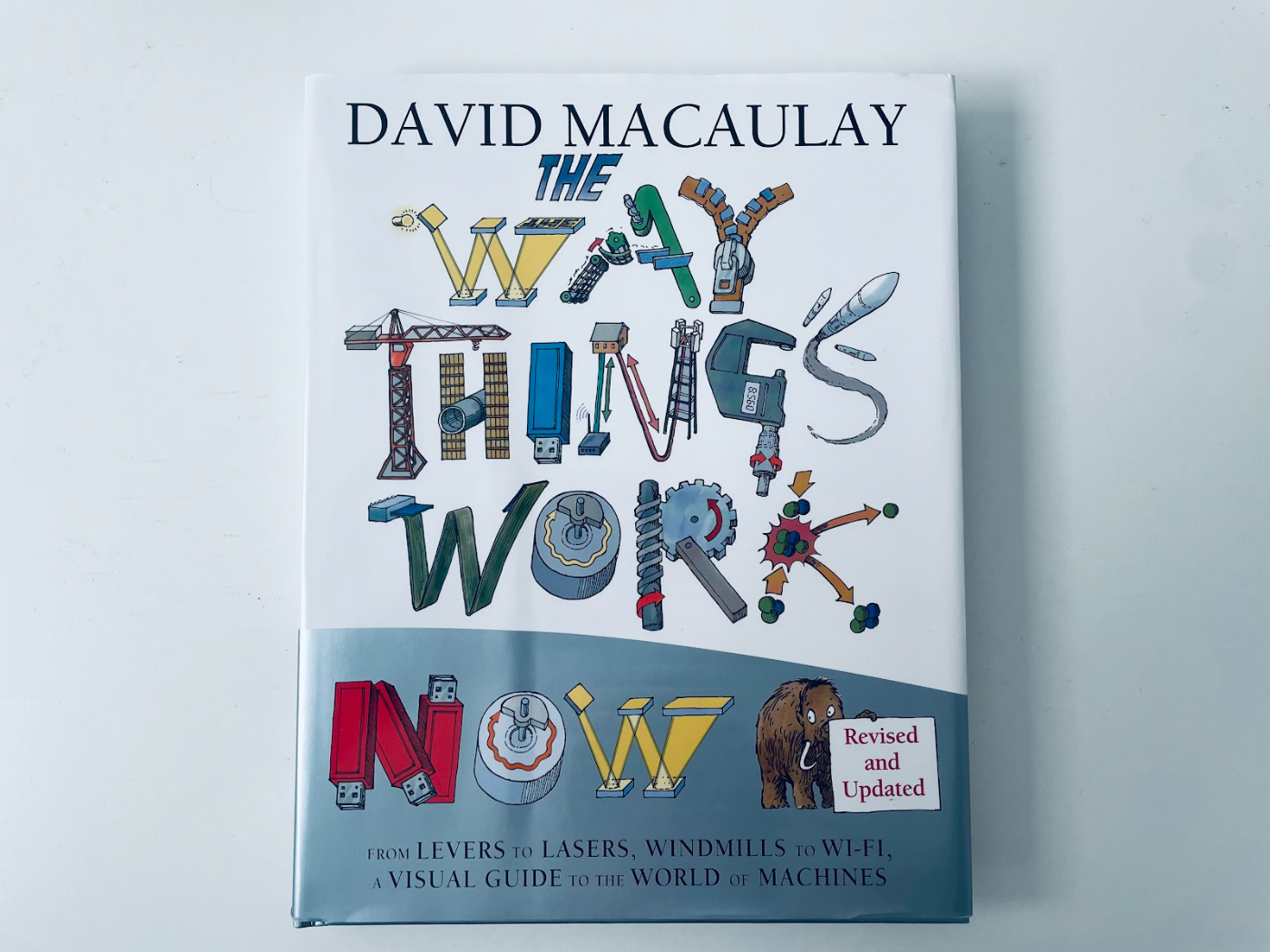

I’ve had a nagging feeling that I should learn more about the physical and mechanical terms that get thrown around in business. So I picked up—and have been devouring—a book called The Way Things Work by David Macaulay.

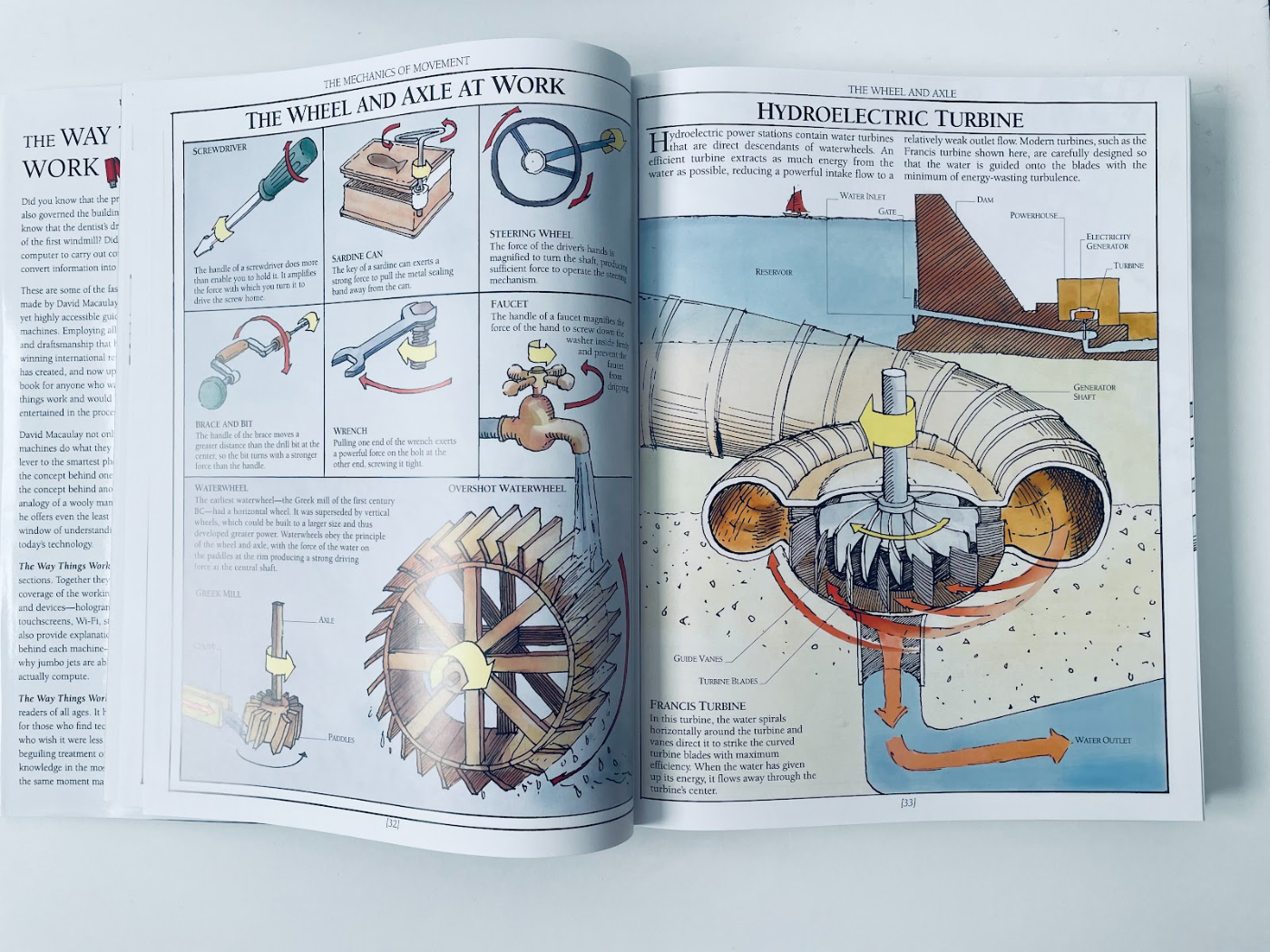

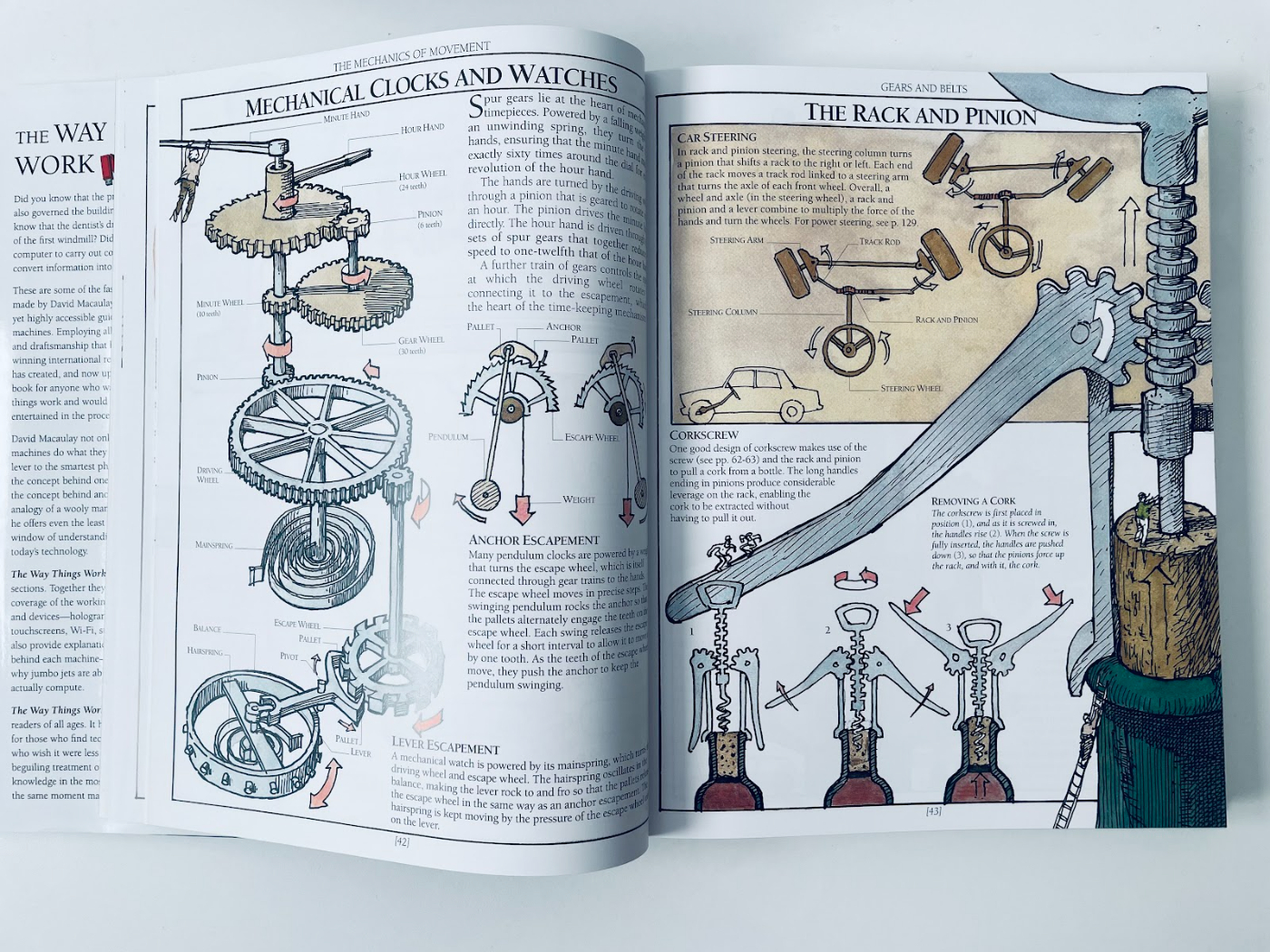

The first chapter is about simple machines like wedges, pulleys, gears, levers, cranks, cams, belts, and more. I had only a foggy idea what most of these were and how they worked before I started reading; it’s been a delight to learn. Each page has short explanations for how these machines work, accompanied by charmingly analog illustrations.

As I turned the pages, it started to dawn on me how an array of tools relies on the same few mechanical principles to work.

Gears, levers, pulleys, wedges, and more are all ways of producing a mechanical advantage: they convert small input forces into larger output forces. The increase in force doesn’t result from these devices having an internal motor; there is no extra energy being created. The way they work is far more clever: they exploit the link between force and distance.

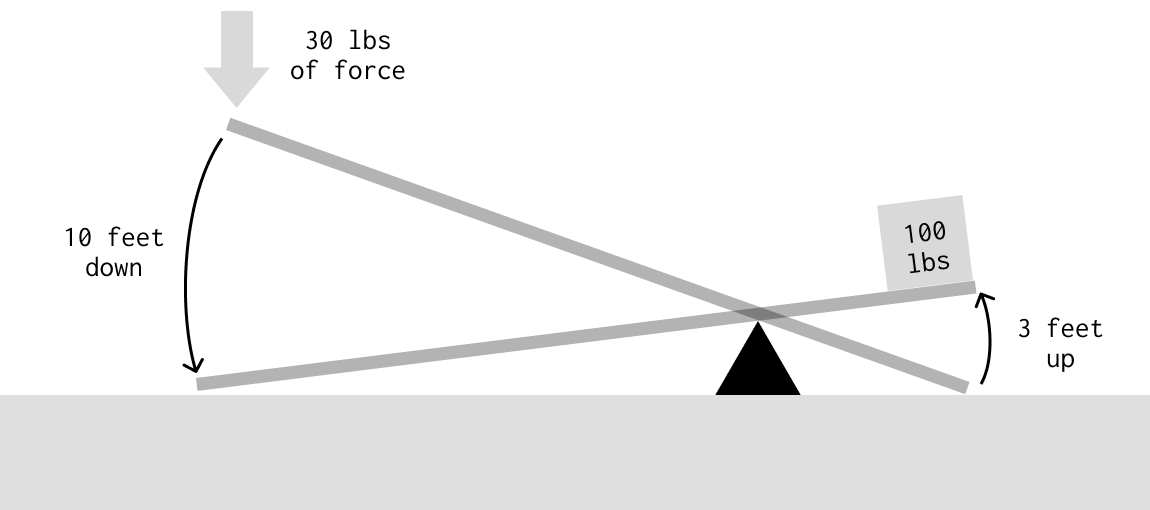

The classic example of a mechanical advantage is a lever, which allows you to lift heavy objects short distances by applying a small force over a larger distance. In the illustration below, when you push down on the left side, the distance the opposite side moves is reduced by ~3.33x, but the force of this movement is magnified by ~3.33x. A useful trade-off!

This same idea of trading distance for force shows up in a surprisingly wide variety of everyday situations.

For example, it’s easier to open a door from the side furthest from the hinge because of leverage. It’s why the door handles are always on that side. With a knife, force is converted from a wide area around the grip to a tiny point at the sharp edge, so it can cut through dense objects like a block of cheese. It’s the same amount of force, but reduced to a tiny space.

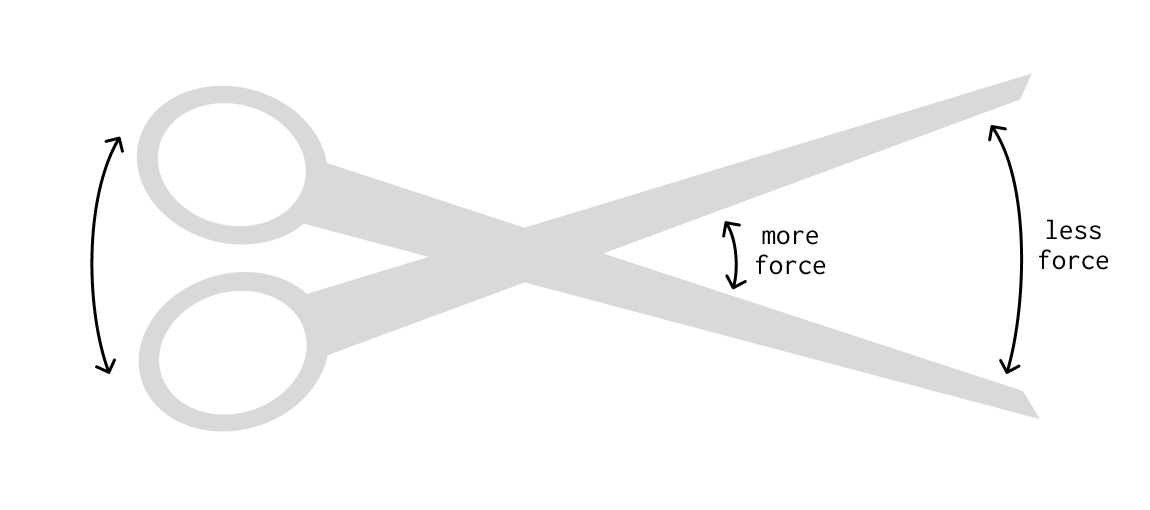

Scissors are like knives and levers combined: the area closest to the hinge cuts with the most force, because the blades travel a shorter distance.

A mechanical advantage is useful in a physical context when you want to overcome resistance, like lifting a heavy object or cutting through something dense. In a business context, there are a few different kinds of resistance.

One is an organization’s inertia. It’s hard to get a company to do a new thing, and the bigger the organization, the harder it is to change. Companies that are trying to change tend to require an equal and opposite force to overcome the inertia. Large enterprise sales teams are built around signing a single customer, while on the small business end of the market all you need is a few quick calls around an otherwise self-serve solution. When an executive wants their company to change, they often hire expensive, high-status consultants like McKinsey to make a plan that gets everyone on board.

If organizational inertia is one form of resistance that you might want to overcome, what are the business equivalents of simple machines that create mechanical advantage and multiply your input force into a much larger output force? And if they exist, do they have an equivalent trade-off of physical machines where you have to apply the force over a longer distance to gain leverage?

Maybe! Startups often hyper-focus on a small number of customers that share specific traits. This compresses all of the startup’s energy and force into a small space. It’s the opposite of being “spread thin.” The advantage of this approach is that you’re more likely to solve a problem, overcome inertia, and gain adoption by the customers you focus on. The trade-off is that it might be questionable how many more customers you’ll be able to find. I call this a market wedge, where you sacrifice scale for power.

Sometimes in mechanical systems you want to do the opposite, and sacrifice power for scale—or, put another way, sacrifice force for distance/speed.

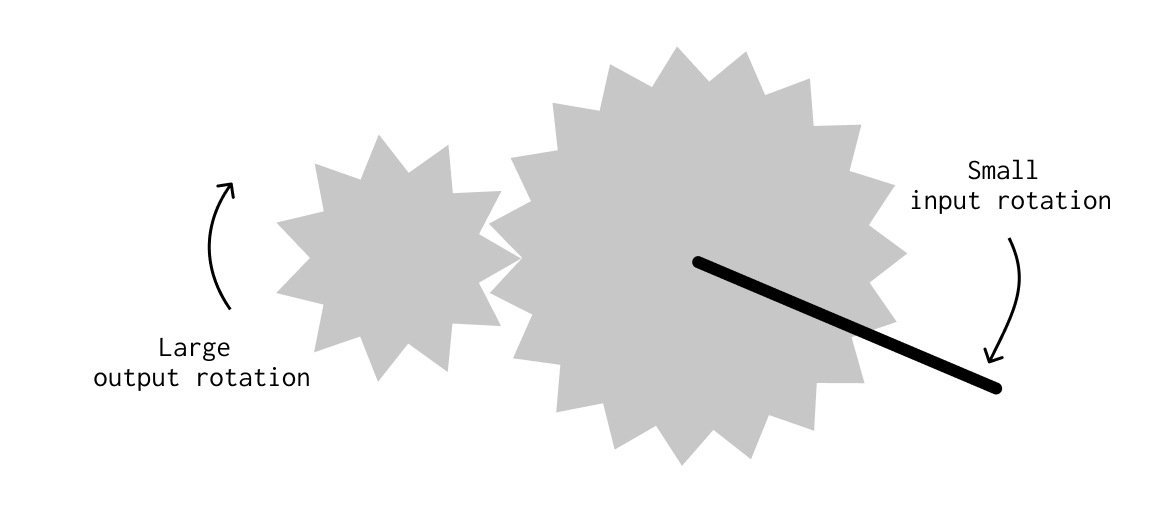

A perfect physical example is a bicycle. When you’re in high gear, each rotation of your pedal turns the wheels many times, thanks to the mechanics of gears.

The trade-off, as anyone knows who’s ever tried to ride uphill in high gear, is that your gain in speed comes at the cost of force. It’s the opposite of leverage. But in some situations, such as riding downhill, that might be exactly what you want.

An analogy in the business world is when companies introduce products that are designed to reach a lot of people, even if they might not make a lot of money or have long-term defensibility. This trade-off can be worth it when you want to establish a lot of new customer relationships, and you’re banking on the fact that you can introduce new products or deepen the value over time. I call this a product wedge, and there are many famous examples. Two of my favorites: 1) Apple’s iPod was an “okay” business on its own, but brilliant in that it bought so many new people into the Apple ecosystem. 2) Instagram’s first users cared more about making photos look good using filters than they did about the Instagram network, because nobody was there yet. But over time Instagram grew a network, which made it far more valuable than a photo editing app.

It’s amazing how the same concepts of mechanical advantage show up in both the physical and business worlds, with each having its own trade-offs to consider. They aren’t perfect analogs, but it’s worth it if it provides inspiration to dig deeper and understand the world around you beneath the surface, beyond having a passing familiarity with the names of things.

Find Out What

Comes Next in Tech.

Start your free trial.

New ideas to help you build the future—in your inbox, every day. Trusted by over 75,000 readers.

SubscribeAlready have an account? Sign in

What's included?

-

Unlimited access to our daily essays by Dan Shipper, Evan Armstrong, and a roster of the best tech writers on the internet

-

Full access to an archive of hundreds of in-depth articles

-

-

Priority access and subscriber-only discounts to courses, events, and more

-

Ad-free experience

-

Access to our Discord community

Comments

Don't have an account? Sign up!