Author’s note: Last weekend Every held a conference in New York called Thesis. I gave a talk called “Narratives Have Network Effects,” but it was limited to 10 minutes, and I had a lot more to say. Plus, I had many conversations with folks at the event that made me want to go even deeper. So I decided to expand it into a full essay, which you are now reading.

Every product we buy, every job we take, every relationship we have, and all the decisions we make are based on narratives—stories that explain how the world works and what’s going on in it. The narratives we believe determine our actions.

A few examples:

- You heard AI is going to change everything, so you quit your job to build a startup using GPT-3.

- You heard countless stories about true love in movies and books, so you broke up with your girlfriend because it didn’t feel the way you thought it should.

- You heard carbs are bad, so you started eating salads for lunch.

If we want to accomplish our goals, we need the narratives driving our actions to be accurate and useful. We also need other people to buy the narratives we believe in if we want to attract customers, investors, employees, or any other kind of partner. So it’s worth understanding where they come from and how they grow.

We all have at least a hazy intuition that narratives have network effects, i.e., popular stories tend to get more popular. But why that is, and what practical advice we can derive from it, is a topic I’ve rarely seen discussed. This is a huge missed opportunity.

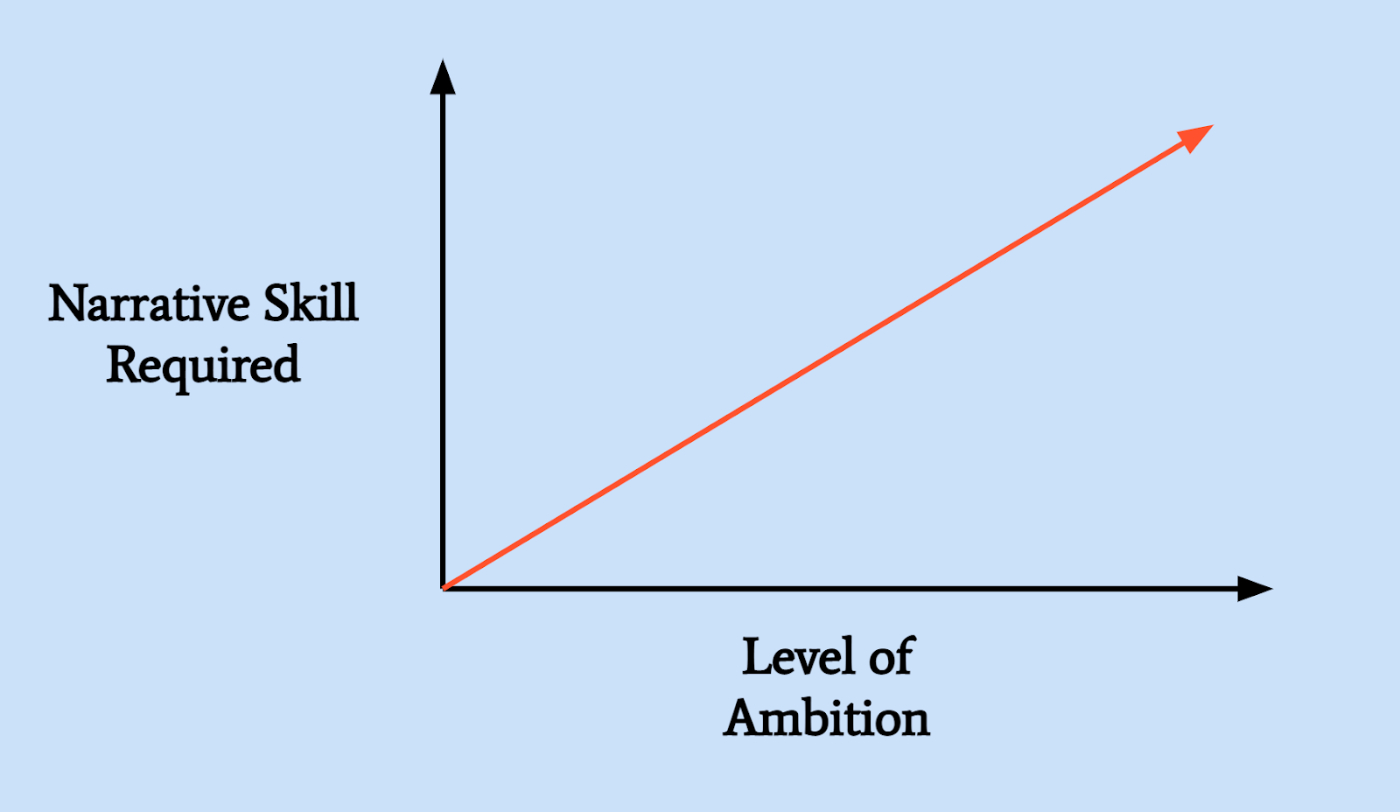

If you just want to get by in life, it’s fine to rely on the default set of narratives that saturate your culture. But the more original and ambitious your goals are, the more you need world-class narrative skills: both on the buy and the sell side.

Of course everybody here already knows that. That’s why you read Every! So given that we’re already narrative aficionados, what else can we do to improve? I would argue that it’s worth it to spend time thinking about the meta question of how narratives themselves emerge and spread. By doing this, we can see more clearly how the ideas surrounding us tend to perpetuate themselves even if they aren’t useful, and we’ll learn how to solve the cold start problem and get our narratives to spread and build network effects of their own.

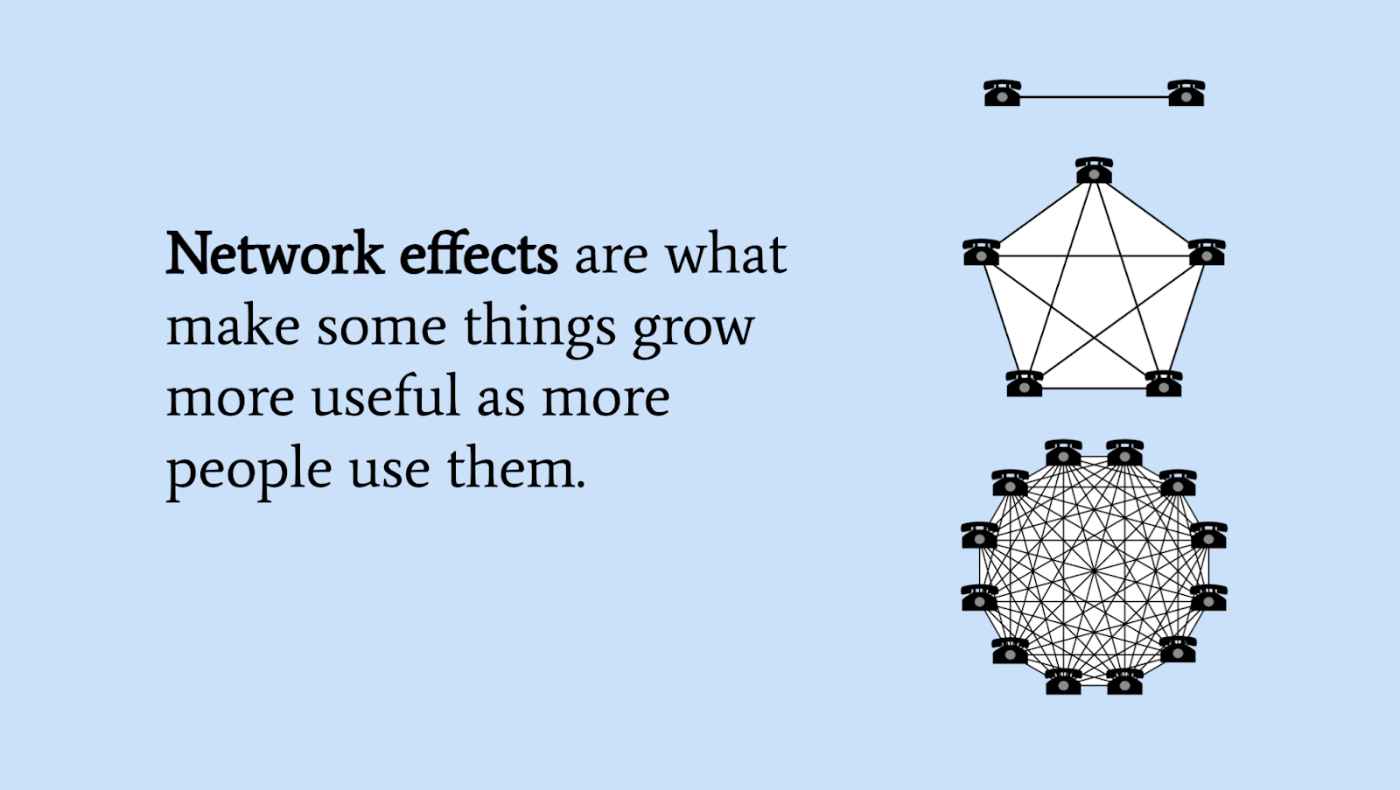

The first thing that probably comes to mind when you hear the term “network effect” is communication technologies like Facebook or the telephone.

The idea is that the value of the network to any single user is equal to the number of other users they can communicate with through it. Therefore the total value of the network is equal to the number of users, squared. Of course no simple formula can capture the dynamic complexity of the value that gets created by networks, but the basic idea is that some things get superlinearly more useful as more people use them.

So, how do network effects apply to narratives? Let me illustrate it with three examples.

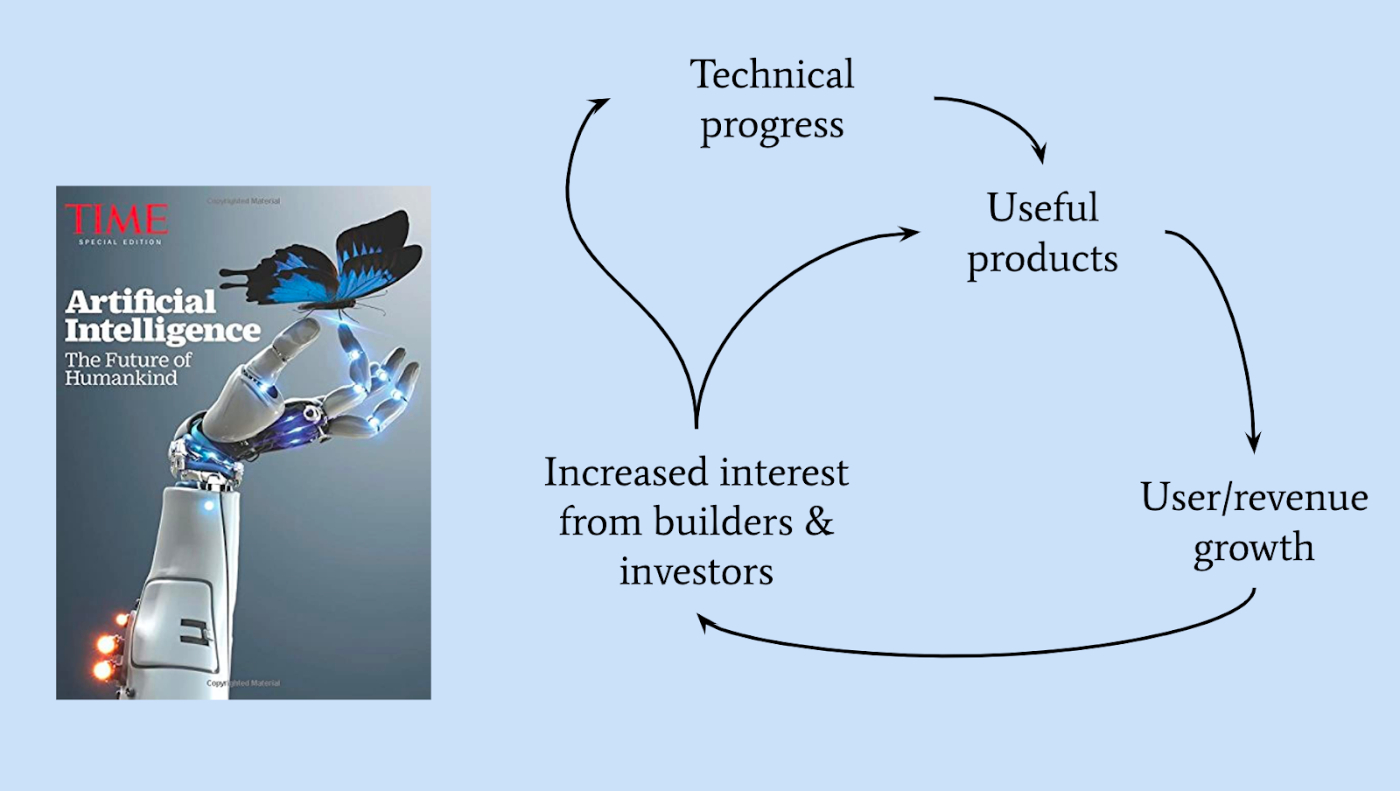

Example 1: “AI will change everything”

The amount of hype and attention AI is getting right now is about 1,000x greater than it was this time last year, but the technology itself is maybe around 2–3x better than it was, at most. That’s a lot better! Real technical progress is an essential part of the story here. But narrative network effects are also crucial. When more people see AI as promising, more people start using it, investing in it, talking about it, and, most importantly, building it, which makes AI become more promising.

Example 2: “New York has great pizza”

When I go to New York, I want to eat pizza. There’s this narrative that it’s a classic New York thing to do and something feels good about participating in that narrative. As a result, there are a lot of pizza places in New York to serve that demand, causing new memories to be made and perpetuating the city’s pizza culture among future generations.

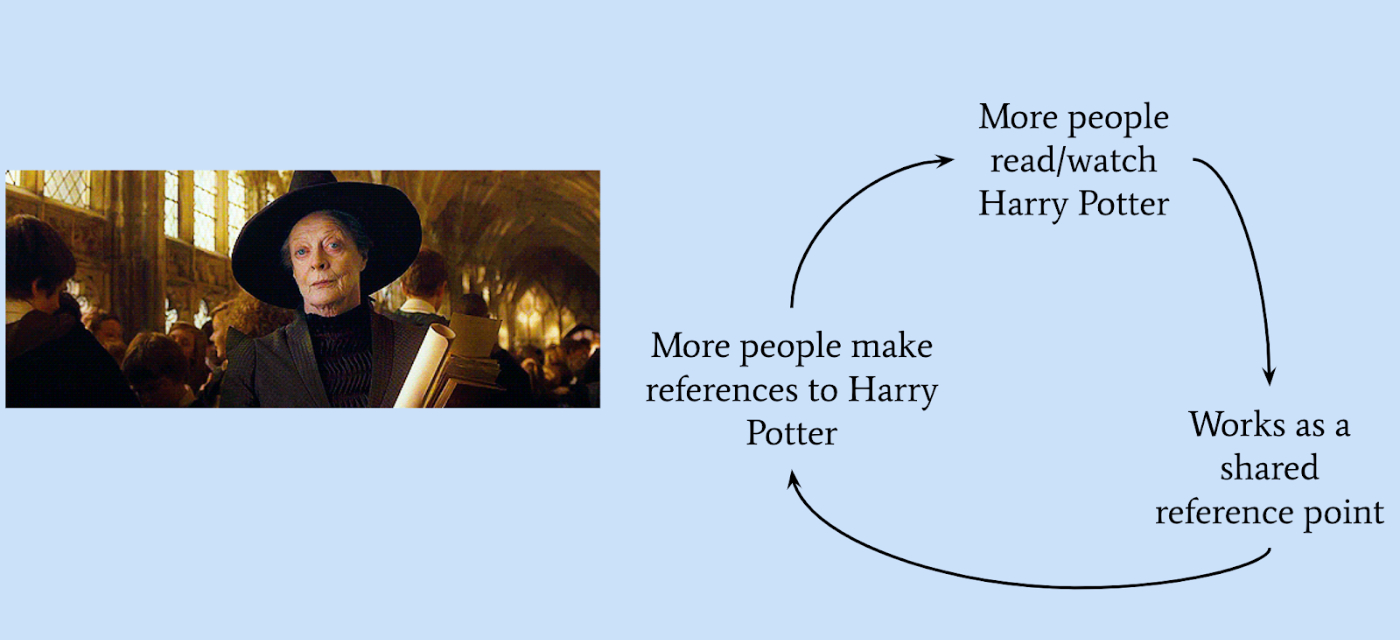

Example 3: “McGonagall disapproves”

When my wife sends me a Harry Potter gif where Professor McGonagall is giving “the look,” I know exactly what it means. (It means I’m in trouble.) The reason that works is because we’ve both seen the movies and read the books.

Allow me to get even more meta for a moment. All of the narratives I chose are pretty well-known narratives. You’re probably familiar with them, and that’s exactly why I chose them! I want you to be able to understand me, and the only way to create understanding is through shared reference points.

This is the fundamental basis of narrative network effects: Without shared narratives, we can’t connect. And every time a narrative gets used, it’s reinforced and is that much more likely to be useful again in the future.

The more popular a narrative becomes, the more deeply entangled it becomes in a culture—and the harder it becomes to operate in that culture without knowing about it.

As I argued in Why Content Is King:

“Having a shared set of narratives, concepts, and symbols is the basis, ultimately, for all culture — religious, national, ethnic, commercial, scientific, etc. How can you operate in biology if you’re not familiar with Darwin? How can you operate in tech if you’re not fluent in Aggregation Theory? You can’t. Even if you think the ideas are wrong, it’s important to understand them so you can understand the things the people around you are saying and doing.”

Two important caveats

Now that we’ve established why narratives can have network effects, it’s important to point out two very important caveats, because there is the potential of significant misunderstanding here without them.

Caveat #1: Narratives aren’t only valuable thanks to network effects

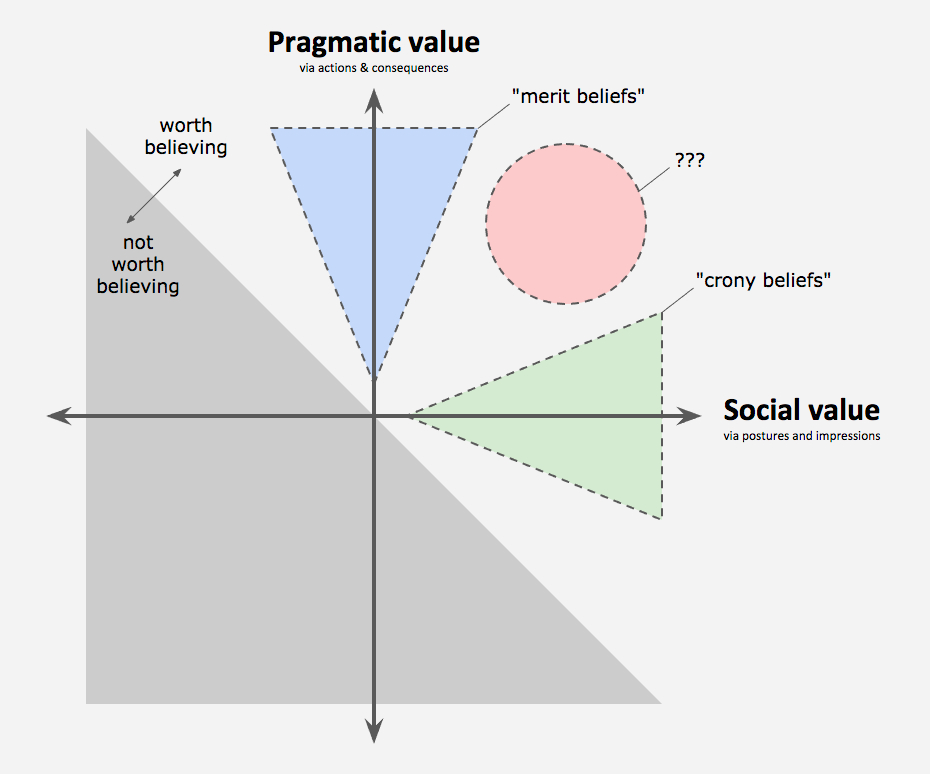

When you believe something about the world and act accordingly, there are two forms of value you can get. One is the sort of “social value” that comes with a shared narrative. But there is also another sort of value that doesn’t care whether anyone shares the narrative or not: It makes sense to call it “intrinsic value.”

For example, even if no one else cared or knew about the science of optics, you could still get value out of inventing the first microscope or telescope if you somehow were able to personally devise a bunch of useful narratives that led you to discovering how light can be warped to magnify small or distant objects.

Similarly, the AI narrative I gave above is dependent on mathematical and physical truths that enable this technology to work. Without them, it would just be an empty hype cycle that produces little lasting value.

On the other hand, there are some narratives that persist even if they have neutral or negative intrinsic value. Kevin Simler wrote an excellent essay about these sorts of narratives, naming them “crony beliefs.”

The idea is that believing in a narrative is sort of like hiring it as an employee that works for us. We depend on the intrinsic value of our beliefs to successfully navigate the world. But we keep around some wildly inaccurate narratives (like flat earth theory, crystal healing, etc.) the same way a company in a corrupt industry might keep around a useless employee because he happens to be the mayor’s nephew. He actually is useful, just on a different dimension.

Here’s an excellent graph that Simler made for his essay. The thing I label “intrinsic value” is called “pragmatic value” here, but it’s basically the same idea:

Caveat #2: Narratives can also have anti-network effects

There are lots of narratives that actually have negative (or anti-) network effects! For example, let’s say you think Peloton is actually going to be a great company in the long run and you want to buy its stock while it’s cheap. The more people who believe this, the more the stock price gets bid up, and the less valuable the narrative becomes.

All of capitalism operates on this principle. It is 100% a real thing.

But that doesn’t mean some narratives can’t also have positive network effects. For example, a whole community rallied around GameStop and AMC, gaining not only short-term speculation value but also longer-term identity and connection. My point isn’t that the social value is more important, just that a narrative can have positive and negative network effects at the same time.

So what? How can we use this?

Let’s say you buy that narratives have network effects. What can we do about it? How can we use this knowledge to help us on the buy side (having more useful narratives in our heads driving our actions) and on the sell side (making our narratives and ideas spread and gain network effects of their own)?

Make better decisions by containing your crony beliefs

We all have crony beliefs—ideas that have little intrinsic value but that we keep around anyway, like the mayor’s nephew, because they make other people like us and reinforce our identity. It would be impossible to fully get rid of these kinds of narratives. The social value they provide is real and, as much as I might daydream about it sometimes, I don’t actually want to live in the wilderness totally alone.

That being said, it’s important to be able to identify and contain our crony beliefs, so that we can put them in their proper place. If you take a crony belief (like crystal healing) too seriously, it can severely limit you. It’s important to know when to go to the doctor, so to speak.

But how can we do it? I don’t have a foolproof guide, but I can share stories of two times I recently realized I had crony beliefs, got rid of them, and am living better now because of it.

The first is when I realized my aspirational identity as an “intellectual” was getting in the way of my health. I was completely uninterested in exercise. I thought running was boring and weightlifting was for jocks and meatheads. I was more of a Belle and Sebastian kind of guy than a barbell guy, and I allowed myself to be trapped by a narrative that said I couldn’t be both.

For a while that narrative served me, because I honestly probably would have gotten funny looks from my friends in college if I started lifting weights, and I liked those friends and believed I would never fit in with the gym people. But the intrinsic value of this narrative was clearly a net negative for my health.

Now I’m older and I have a kid, and so I started thinking more about my longevity and—OK, stop, record scratch. That’s partly true, but if I’m being really honest it’s not the whole story. Has anyone else noticed how health and fitness content got really popular in tech twitter over the past few years? Of course that had nothing to do with my choice to start working out more! And I’m sure none of you were influenced by that either :)

What this story shows is that intrinsic value and social value aren’t opposed. They are independent variables. The intrinsic value of buying into the “fitness” narrative stayed mostly constant throughout my life, but the social value shifted and made it easier (possible?) for me to get started lifting weights. The moral of the story? Choose social scenes that reward narratives with high intrinsic value.

That being said, no scene is perfect. Sometimes you’ll need to go against the grain if you want to get the most out of life. And that’s what the next (quick) story is about.

I have a confession to make: Recently I started listening to country music… and I kind of love it. I grew up in Arkansas, but I always wanted to leave and be more of a city person. But recently I heard a country song playing and thought, “You know, I actually like this.” The song told a relatable story. It had a great melody and harmony. I knew I wasn’t supposed to like it, but why? Ah, narratives. I thought country music was for Republicans. Maybe some of it is, but mostly it’s about breakups and self-destructive tendencies, in my experience. Plus, it reminds me of home. Why deprive myself? I’m glad I don’t anymore.

This is perhaps a somewhat trivial example, but I think it’s important to start small and learn that it’s OK to do things that aren’t cool (or are even to some extent frowned upon) when you know you aren’t harming anyone. It’s practice for the times when the stakes will be higher.

Grow new ideas by solving the cold start problem

It’s hard to pitch new ideas because they often don’t fit with the narratives people already believe. Every new narrative we accept has to accord with our existing set of narratives.

“But what about evidence? Don’t people update their beliefs when presented with evidence?” Ha! Not really. Instead, we search for reasons the evidence is wrong or doesn’t take important facts into account. Or we just suspect there probably is something wrong with it and go about our day.

So how can we get people to accept a new idea? Show how it is a natural extension of the things they already believe. Sure, evidence also helps, but no amount of evidence will make someone believe a story they’re skeptical of.

The other thing you can do is start with a group of people who are already inclined to believe the prerequisite narratives they’d need to accept to be interested in your new narrative. For instance, if you have a web3 startup, you should probably mostly stay within the web3 community if you want to gain users and investors. (Especially right now, when prices and morale are low.)

This is such a huge subject it should be its own essay, but I think it would be really helpful to go through all the canonical startup advice about overcoming the cold start (or “chicken and egg”) problem, and applying it to other domains where it doesn’t seem like it would apply. Because truly there are an incredible variety of scenarios where you face this kind of problem, due to narrative network effects:

- Starting a career is about building a reputation, i.e., a narrative about yourself. The more people believe it, the more opportunities you get to prove yourself, the more you can move ahead quickly.

- Actors and musicians are popular in part because they are popular. People like to hear familiar songs and see familiar faces.

- Crowded restaurants and bars feel “alive,” which draws a crowd. Plus, people like to go to cool places that are well known.

(I could go on for a long time!)

Be patient

When I showed a draft of this piece to my co-founder Dan, he pointed out another important point about network effects that apply to narratives. Because network effects are an exponential function, it can feel as if not much is happening for a really long time even though you’re on the right path.

As Chris Dixon put it, exponential curves feel gradual and then sudden.

Future study

But beyond the practical economic value of being a skilled creator and consumer of narratives, it’s fascinating from a scientific perspective to try to get a clearer understanding of why people do what they do. Maybe in the future it will be possible to have something similar to the psychohistory that science fiction author Isaac Asimov dreamed of, and we’ll be able to make accurate predictions about the behavior of large groups of people.

If I had to bet on the most promising starting point for how we could get there, I’d bet on the study of narrative network effects.

Find Out What

Comes Next in Tech.

Start your free trial.

New ideas to help you build the future—in your inbox, every day. Trusted by over 75,000 readers.

SubscribeAlready have an account? Sign in

What's included?

-

Unlimited access to our daily essays by Dan Shipper, Evan Armstrong, and a roster of the best tech writers on the internet

-

Full access to an archive of hundreds of in-depth articles

-

-

Priority access and subscriber-only discounts to courses, events, and more

-

Ad-free experience

-

Access to our Discord community

Comments

Don't have an account? Sign up!

Brilliant!