Sponsored By: Morning Brew

Join over 4 million people by reading Morning Brew - the free daily newsletter covering all things business from Wall Street to Silicon Valley.

Let's face it: traditional business news is dry, dense, & boring. But Morning Brew is written in a witty yet informative tone that makes reading the news actually enjoyable.

Best part? It's 100% free and only takes 5 minutes to read, so that you can get all of the most relevant updates and move on with your day.

My wife and I recently bought our first home and we’re expecting our first child soon, so, as you can imagine, we’ve been doing a lot of work to get the place ready. One of our favorite ways to help pass the time while we organize cabinets and unpack books is to put a TV show on in the background. Our favorite genre these days is culinary competitions.

Of everything we’ve watched, there are two shows that stand out to me because they are perfect opposites: Top Chef and The Great British Bake-Off. Some day I’d like to watch these shows with my kid, because I think the contrast between the two wonderfully illustrates what competition can do to you if you’re not careful, and yet how fun it can be if you create the right environment.

The basic premise of the two shows is the same: a group of chefs/bakers competes in 2-3 challenges per episode. There are no teams—everyone is judged individually. Each episode has a theme like “biscuits week” or “seafood week”, where there is a winner (who gets nothing tangible, just honor and a target on their back) and a loser (who has to go home). The judges are firm, but fair. As the season progresses, the group of contestants gets smaller and the stakes get bigger, until the grand finale, where one person is declared the winner. This transforms their career.

Competition shows are inherently zero-sum games. If I win, you have to lose. This turns cooking—something we normally do for reasons practical (feeding our family), professional (run a profitable bakery/restaurant), or creative (invent a unique dish)—into a sport. In the real world there need not be winners and losers in the pursuit of transforming raw ingredients into edible delights, but the drama of winning and losing is what makes it work on TV.

You might think this zero-sum setup means the rivalry between contestants has to be intense, but what stood out to me when watching Top Chef and The Great British Bake-Off side by side is just how different the competitive environment can feel. There is an incredibly wide range.

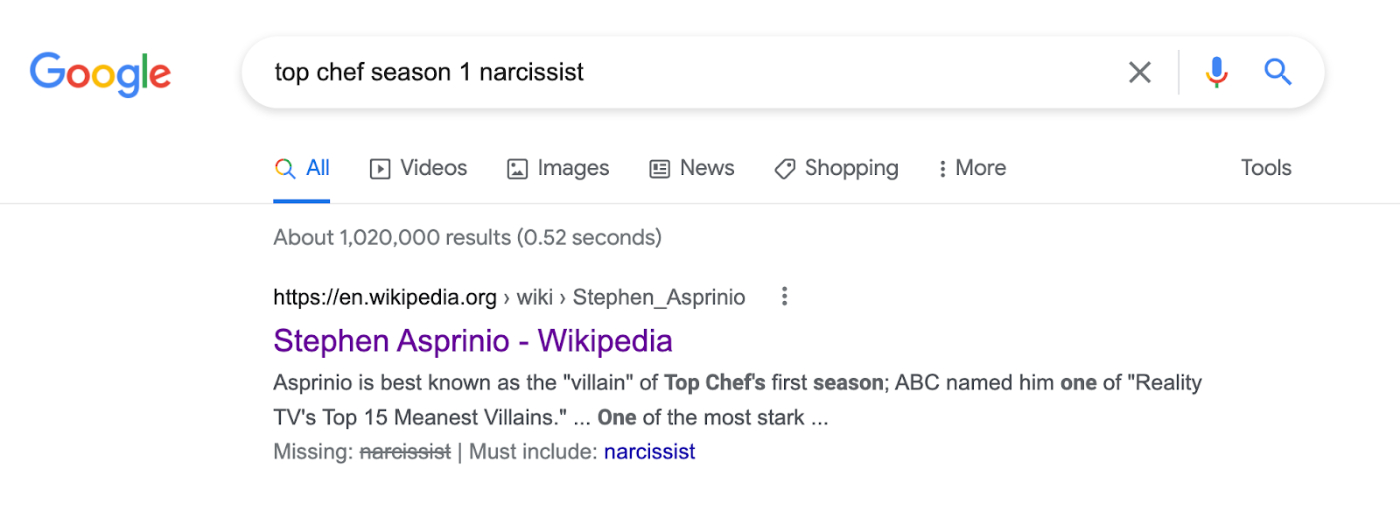

On Top Chef (at least in season 1, which is as far as we got) I saw contestants keep secrets from each other, try to bend the rules by asking for a little extra time, and attempt to sabotage each other by suspiciously leaving shared oven doors open. At times the show seems like it was designed to create acrimony. In the first episode they divided the chefs into two groups, and had each one cook a meal for the other group to taste and critique. Let’s just say shit-talking was not frowned upon! It also seems like the casting directors explicitly looked for a few people with narcissistic personality disorder. One guy was actually named in ABC’s list of "Reality TV's Top 15 Meanest Villains" and called a fellow contestant “trash”.

Hilariously, I forgot the guy’s name, but found it when googling “top chef season 1 narcissist”. His Wikipedia page was the first result.

Meanwhile, on The Great British Bake-Off, in nearly every episode I saw bakers helping each other out when they struggled to finish a challenge or simply needed a hand. In every episode bakers genuinely cheer for each other when someone has a good bake, and literally cry and hug each other when someone gets sent home. The most mind-bending thing to me was at the end of every season the second and third place finalists seem genuinely thrilled rather than devastated or aggrieved—they always say they’re just happy to have had such a wonderful experience, making new friends and growing as a baker. Oh, and they always say (and seem to genuinely believe) the winning baker truly deserved it. One suspects their self-worth doesn’t depend on winning televised baking competitions. When the show ends, there’s always a photo montage of contestants hanging out together at picnics, on road trips, and at reunions of all sorts.

The world is awash in conversations about supportive and toxic environments, to the point where the words have nearly lost all meaning. But there’s a reason why people talk about it so much: it’s important. If you need a reminder, just watch these two shows side by side. One will leave you feeling the warm and fuzzies of a wedding or baby shower, the other will make you feel like you just escaped the high-school cafeteria of your nightmares.

Human nature isn’t pure evil or good. We do not always cooperate or always defect. Both strategies are available to us, and emerge in any given situation based on a complex interplay of factors like resource scarcity, information transparency, etc. But we do have some influence over what sort of environment we create, in two ways:

- How we play shapes how others play

- Where we play shapes what games matter

In other words, if you want your lived experience to be more like The Great British Bake-Off and less like Top Chef, you can do two things.

First, no matter what game you’re playing, you can seed a cooperative culture through your own actions and example. That doesn’t mean letting other people walk all over you—when someone is a jerk or narcissist it’s important to defend yourself, the people around you, and more generally the values of cooperation. But it does mean that if you want the benefits of a supportive environment the most important thing you can do is to support others. This might sound pollyannaish, but it’s actually supported in the game theory literature. There is a strategy called “tit-for-tat” that basically defaults to cooperation, then retaliates if it is defected against.

The second thing you can do is to invest your energy into environments that are already cooperative, thereby making those games bigger and more successful. Games, like any sort of network, generally become more powerful as more people play them. If there is overwhelming demand to watch and be a part of The Great British Bake-Off universe, then they can do spin-offs, they can reward players more richly, and their cultural impact gets bigger. Same goes for a company in attracting customers and employees, or a social network or community in attracting users and members.

When a cooperative culture emerges like this, there needs to be a sort of protective trust bubble that prevents assholes from exploiting and ruining the environment. This is easy to enforce in a closed system like a competition show: the producers of Top Chef and Great British Bake-Off control who gets on the show, and I’m pretty certain they screen for personality type in addition to culinary skill. But it’s much harder to enforce when it comes to more open systems like industries.

For example, say there was a friendly neighborhood street with a couple restaurants that all respected each other. Then an outsider came in who didn’t care about anything except winning. Perhaps this could be a good thing, in some cases! Maybe they compete by offering better experience at lower prices, benefiting consumers. (Remember, “collusion” is a synonym for cooperation!) But maybe there are other actions they take that we can all agree are net bad for the environment. Maybe they make up lies about their competitors (they have rats in the kitchen!) and spread them through whisper campaigns. Maybe they secretly slip mild poison into their ingredients, giving their customers gastrointestinal distress. Or maybe they just come on the block generally acting like jerks and narcissists, killing the vibes.

Before I move onto the solution to this problem where it’s harder for a community to coordinate to protect its values, I want to dwell on this last harm a bit because it might seem trivial, but I think it’s actually incredibly important, and it’s the hardest value to protect. When someone does something egregious like outright sabotage, it’s easy for a community to rally around and shun the villain. That’s why we don’t see this kind of obviously awful behavior that often: people know the risk is extremely high if they are caught. But the far more common sort of defection we experience in an ecosystem is just people killing the vibes by being jerks. For example your coworker probably isn’t going to sabotage your project so they get promoted and you don’t, but they might just subtly be a jerk towards you and make your morning standup stressful rather than fun. This kind of harm is so hard to guard against precisely because it’s less obvious. But it does matter. If I had to pin down the most important difference between Top Chef and The Great British Bake-Off, the most overt examples of harm aren’t the most important to me. It’s the general anxiety and drama of one as compared to the fun and creativity of the other.

So, how do we solve this? How do we deal with subtle defection? Easy: make it obvious.

At the risk of being a hammer who sees everything as a nail, this is a job that I think writers can help with. For example, if I had to guess how often “manspreading” happens on New York subways today vs before that term was coined, I would guess there’s substantially less today than there was in the past. Of course not everyone who manspreads on the subway has heard that term, but of the people who have, I bet a substantial portion have stopped doing it.

Once a negative pattern of behavior is named, it can be identified. And once it can be identified, it can be shunned. Names for negative patterns of behavior are like public goods: they benefit all of us, we can all use them, and the more we use them the more useful and effective they become.

The challenge is to articulate clearly why a behavior sucks, how it impacts people, and why it shouldn’t be done in a way that can cut through the noise. Manspreading is such a great example because it is so clear. Other examples like “abuse” and “toxicity” are less good because they are so imprecise they can be applied to any situation. If writers want to make an impact on culture they need to be precise.

There is another challenge, though: tribalism and culture wars. There are some spheres of society in which there is very little shared framework of understanding how the world works and what constitutes harm vs benefit. In those cases, it’s going to be extremely challenging to come up with memes that everyone can agree upon. For example, right now Marc Andressen is trying hard to make “the current thing” meme a thing. The basic idea is that it’s bad to blindly support “the current thing” especially when that means uncritical support of any proposed solution to the current thing. I can see some of the point behind what he’s saying, but also I can see how people might trot the meme out as a lazy way of disagreeing with anything people are advocating for at the moment. “You’re just supporting this because you’re a sheep, not because it actually matters to you.” Uh, ok.

There’s no easy answer to the tribalism problem. If you want a supportive and cooperative environment, I don’t think we’re ever going to find it at the global level. And maybe the dream of global harmony is actually a nightmare, something we shouldn’t wish for. Maybe it’s great for small communities like your company or a baking competition to be supportive and nurturing, but maybe we shouldn’t apply the same moral lens to the entire world. I would really like for the world to be able to cooperate more and for there to be more mutual understanding, but something about that seems like if we go too far in that direction it might trade off with important values like freedom and diversity. I’d rather have rambunctious and sometimes even acrimonious pluralism than a harmonious worldwide monoculture, as long as we can get our shit together enough to address existential risks. Of course, in light of the recent past, this is an open question.

Either way, it will be fun to talk about with my kid someday!

Find Out What

Comes Next in Tech.

Start your free trial.

New ideas to help you build the future—in your inbox, every day. Trusted by over 75,000 readers.

SubscribeAlready have an account? Sign in

What's included?

-

Unlimited access to our daily essays by Dan Shipper, Evan Armstrong, and a roster of the best tech writers on the internet

-

Full access to an archive of hundreds of in-depth articles

-

-

Priority access and subscriber-only discounts to courses, events, and more

-

Ad-free experience

-

Access to our Discord community

Thanks to our Sponsor: Morning Brew

Morning Brew's daily email will keep you up to date on the most important business, finance, & tech news so that you can outsmart your friends, family, & coworkers.

Comments

Don't have an account? Sign up!