Welcome to part 3 of my series on disruption theory!

In part 1, we covered the classic version of the theory as articulated by Clay Christensen in the 90s. And then in part 2, we explored Ben Thompson’s critique of disruption. Now, we’re turning our attention towards an up-and-coming and massively underrated strategy thinker: Alex Danco!

Alex works at Shopify now, but I first encountered his work back in 2016 when he published a series of essays called “Emergent Layers” that blew my mind. Luckily, his thoughts on disruption are equally compelling.

Danco has written two main posts trying to patch disruption theory in order to fix its failed predictions about the iPhone, Uber, MOOCs, etc.

The first was wonderful, and I can’t recommend it more highly. It suggests that Apple has avoided disruption not because consumers have infinite demand for quality user experience, as Ben Thompson argues, but rather because Apple deliberately and strategically raises our expectations and inspires us to want more. Sure, it’s a lofty aspiration, but I actually think it’s applicable even for startups.

Danco’s second critique of disruption was... less good. It says disruption today happens at the level of ecosystems of companies, rather than individual firms. But I think this actually fits pretty well with classic disruption theory, and isn’t that useful or new of a distinction.

Let’s dive in!

1. Apple’s antidote to disruption? Raising expectations.

You can only get disrupted if your product’s performance overshoots what your customers care about. And both Alex Danco and Ben Thompson agree that the reason Apple has avoided disruption is that their customers continue to demand more from them.

But why?

While Thompson says that consumers inherently have infinite demand for a better “user experience”, Danco instead focuses on the ways that Apple intentionally and strategically raises customer expectations, which gives them the headroom to keep improving performance without overshooting what people want. In Danco’s understanding of the world, customers don’t inherently prioritize superior user experiences. Apple instead makes them value it by raising their expectations and inspiring them to believe that previously unimaginable experiences are just now on the verge of possibility.

This goes against most startup founders’ assumption that demand is something that’s out there, that you can potentially serve, but cannot influence in any meaningful way.

But what if you could? Especially for a company with the visibility and resources of Apple, it’s not a huge stretch.

And the idea is not without precedent. In 1958, a Harvard economist named John Galbraith wrote The Affluent Society, arguing that most consumer demand beyond our basic needs was created by advertising.

If you’re having trouble sympathizing with this point of view, try to remember how it felt when you first saw an advertisement for the iPhone. A screen of pure glass! Incredible. All your previous expectations for what a phone could be were made obsolete in an instant. At least that’s how it was for me.

(And then you use the product, and it’s definitely better than what came before, but you’d still like it to be so much better. You now demand more.)

When you think about it, you realize this is the master key that unlocks the genius of all iconic Apple products. When they first launched, they represented an inspiring new category that just barely works and pushes the limits of science and engineering. And they were advertised in a way that changed our sense of what’s possible.

Just roll down the list of iconic Apple products, and you can see this theme in all of them:

- FaceTime

- AirPods

- iPad

- iPod

- The original Macintosh

- Carplay

- Siri

- MacBook Air

- Apple Watch

- Apple Pencil

- AirPower charging mat (maybe?!)

- Apple Glasses (almost certainly)

The thing all these products have in common is they raise our expectations. They’re essentially selling the “flying car” of every product category they choose to compete in. At first it seems fictional.

In fact, Apple’s competitors literally didn’t believe the iPhone was possible when they first announced it!

“I left RIM back in 2006 just months before the iPhone launched and I remember talking to friends from RIM and Microsoft about what their teams thought about it at the time. Everyone was utterly shocked. RIM was even in denial the day after the iPhone was announced with all hands meets claiming all manner of weird things about iPhone: it couldn’t do what they were demonstrating without an insanely power hungry processor, it must have terrible battery life, etc. Imagine their surprise when they disassembled an iPhone for the first time and found that the phone was a battery with a tiny logic board strapped to it. It was ridiculous, it was brilliant.”

This story is hilarious, but also contains an important lesson:

Before the iPhone, our expectations of what a phone could be were low. After they launched the iPhone, our expectations went through the roof. The iPhone created an entirely new consumer need. And the first iPhone just barely met the need — leaving plenty of room for further innovation and sales.

It’s not just Apple that has done this. Amazon inspires us with visions of 1-hour drone delivery, and perfectly intelligent voice assistants. Tesla has us dreaming about an electric future. Marketers are left speechless by Facebook and Google’s newest ad targeting innovations. You get the idea.

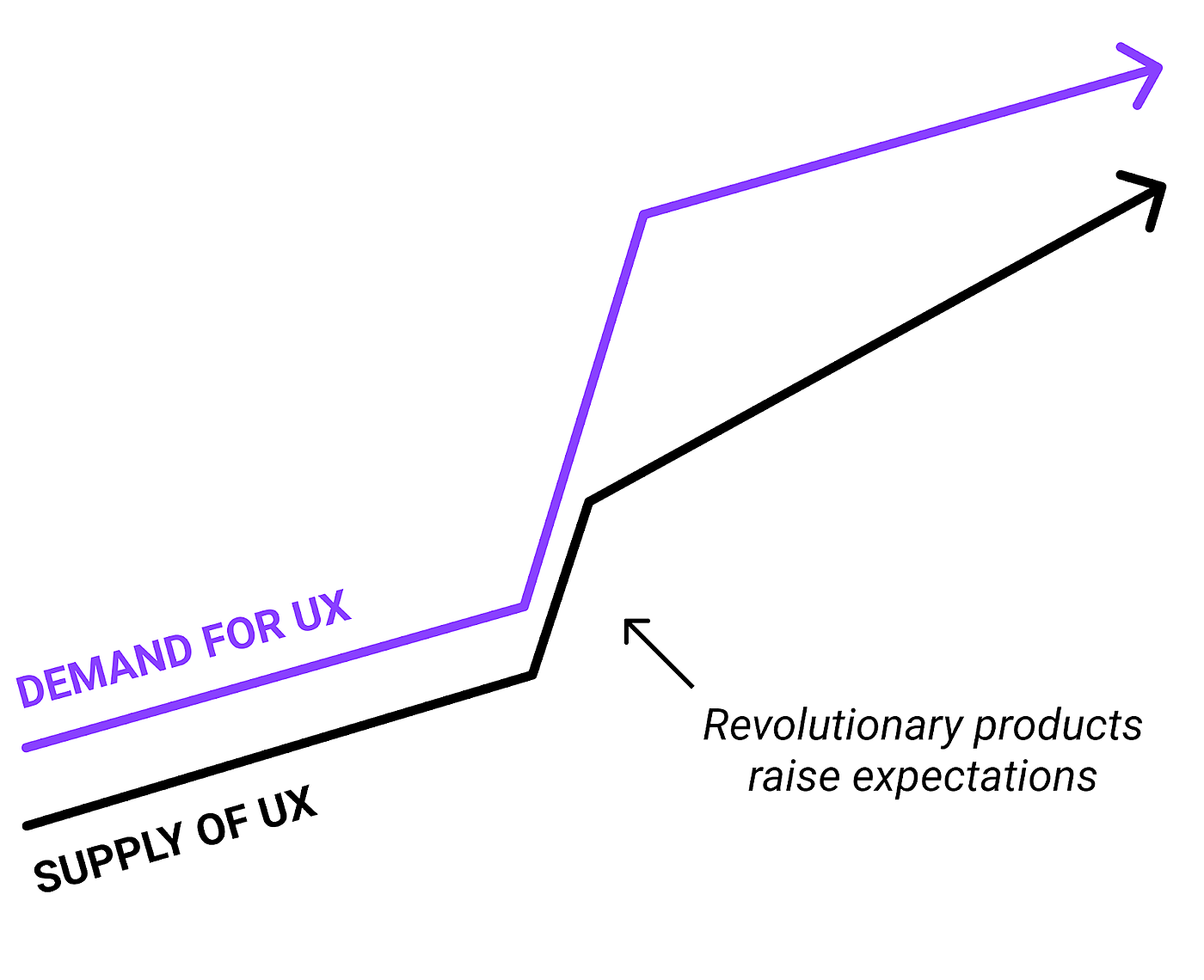

There’s a generalizable lesson here: revolutionary products raise expectations. If you can inspire customers with your progress and your aspirations, you can create demand for increased performance.

Of course, it’s easy to make a big promise, but much harder to actually deliver on it consistently over time. Just ask Magic Leap! The point here isn’t to disconnect your marketing from reality, it’s to understand that consumer expectations are not static, and can be influenced by great companies in ways that don’t just create hype, but actually create a defense against disruptive entrants.

One interesting implication of this theory is that marketing has a more central role to value creation than has previously been understood. Normally, when you hear people talk about marketing, they basically think of it as a cost center that is required in order to get people to find out about the product. But what if marketing — telling inspiring stories that cause customers to care more, demand more, and value more — is central to Apple’s moat?

Could you apply this to your business? Would it change the level of investment you allocate to storytelling?

I find this idea that marketing raises expectations to be incredibly compelling and underrated. It’s buried in a rarely-referenced post Alex Danco wrote back in 2015, but to me it convincingly explains a core reason why Apple is one of the most valuable companies of the world, and suggests a playbook for other businesses to copy.

That post is so underrated, Alex himself even under-rates it! He later called the idea an obvious platitude. Either I’m incredibly naïve, or Alex is seriously underestimating the usefulness of his own idea.

Based on my assessment of his second post on disruption, I’m betting it’s the latter.

2. Disruptive ecosystems can be composed of sustaining innovations

In Alex Danco’s second post critiquing disruption, he argues that the theory describes something real, but the actual disruptive force in today’s markets is not individual companies, but instead ecosystems of interdependent businesses that may look like sustaining innovations if you view them in isolation.

This distinction between disruptive and sustaining innovations is one of the central ideas in classic disruption theory, so it’s worth unpacking before we move forward.

Disruptive innovations do something people want in a new way that’s probably cheaper, more accessible, simpler, and/or more customizable. Their appeal is based on a different dimension of quality than products in the space historically focused on. They’re not useful at first to the buyers in the high-end of the market, but as the technology improves over time, they can be. For example, Ikea DIY furniture is disruptive relative to traditional furniture, smartphones are disruptive relative to laptops, and Substacks like mine are disruptive relative to newspapers, magazines, and books.

Sustaining innovations make an existing thing even better at the dimension of performance people at the high-end of the market care about most. When Canon introduces an even more fancy high-end camera, or Apple releases an even more fancy smartphone, these are said to be sustaining innovations.

Disruption theory predicts that startups who come to market with sustaining innovations will often fail. This is because sustaining innovations appeal to the incumbents’ best customers, so they have every incentive to retaliate (aka copy).

The only problem is, some of the biggest startup successes were based on sustaining innovations. Uber is perhaps the prime example. So why did they succeed when they were targeting the high end of the taxi market? Another example is Apple’s entrance into the smartphone business with the iPhone, which was targeting the high end of the smartphone market.

Alex Danco makes sense of these anomalies by arguing that even though the iPhone and Uber look like sustaining innovations, they’re actually a part of a larger network of businesses that is classically disruptive.

For example, if you look at the iPhone and compare it to previous smartphones, it’s clearly a sustaining innovation targeting the high end of the market. But the whole point of the iPhone is that people use it for a wide variety of jobs that they didn’t previously hire their smartphones to do. Take photography, for example. Before the iPhone, photography was expensive. You had to buy a stand-alone device. Then you’d print photos and mail them to people. Or you’d just show them an album when people came over to your house.

But then the mobile photo ecosystem disrupted photography from below. At first smartphone cameras were just a toy for teenagers, not worthy of serious occasions. But then the hardware kept improving, the photo and video quality became competitive, and the mechanisms for sharing became much better. Instead of printing and mailing, we switched to Instagram (another seemingly high-end product), and gradually digital camera makers and their entire value network retreated upmarket to the increasingly tiny segment of customers that require more quality than smartphones can provide.

So even though the iPhone is a sustaining innovation relative to Nokia and Blackberry, it was still a disruptive innovation relative to Canon and Kodak, especially when paired with complementary businesses like Instagram. It’s this larger ecosystem level that Alex thinks is the right way to view disruption today.

This is perfectly sensible! The only problem with Alex’s theory is that it’s also perfectly compatible with classic disruption theory.

Clay Christensen doesn’t just speak of individual companies disrupting each other — he recognizes that companies exist in ecosystems, and actually coined the term “value network” to describe how this happens. The reason Christensen failed to predict the success of the iPhone wasn’t because he couldn’t conceive of ecosystems as the primary unit of disruption, it because he was comparing the iPhone to other smartphones, rather than the larger incumbent ecosystems built around the jobs the iPhone would subsume, like photography, web browsing, maps, and notetaking.

The iPhone may have been sustaining relative to other smartphones, but smartphones generally were clearly disruptive relative to their desktop and analog antecedents.

But that shouldn’t matter, according to the theory. Nokia, RIM, Microsoft, and others were already there, trying to build the same kinds of things Apple was trying to build. If there are any powerful businesses that you are a sustaining innovation relative to, then disruption theory predicts that they will copy and crush you. It doesn’t matter if your cohort of companies is generally disruptive relative to some other set of incumbents.

Perhaps the key mistake in Christensen’s analysis was a failure to recognize how much Apple’s existing resources and DNA as a consumer computer creator would give it a head start in building a great smartphone than rivals that had grown up in the dumb phone business. If incumbency is defined by unfair advantages, maybe Apple was, in some ways, actually more of an incumbent than Nokia and RIM?

Either way, I seriously doubt that Christensen didn’t realize that disruption can happen on the level of ecosystems, rather than individual companies. So I’m personally not nearly as big a fan of Alex’s more recent critique of disruption. Not because I think Alex is wrong about ecosystems disrupting incumbents, but more because I don’t think it’s actually contrary to the classic account of disruption.

The bigger issue is understanding what you should compare a new product to, and how you should determine who has incumbency advantages. In theory these labels are clean and obvious, but reality is complicated. Most new products are sustaining relative to some set of immediate competitors, and disruptive relative to others.

So how can we predict their fate if we don’t have a basis for deciding where it fits?

Stay tuned for next week! Hamilton Helmer will help us out :)

What’d you think of this post?

Find Out What

Comes Next in Tech.

Start your free trial.

New ideas to help you build the future—in your inbox, every day. Trusted by over 75,000 readers.

SubscribeAlready have an account? Sign in

What's included?

-

Unlimited access to our daily essays by Dan Shipper, Evan Armstrong, and a roster of the best tech writers on the internet

-

Full access to an archive of hundreds of in-depth articles

-

-

Priority access and subscriber-only discounts to courses, events, and more

-

Ad-free experience

-

Access to our Discord community

Comments

Don't have an account? Sign up!