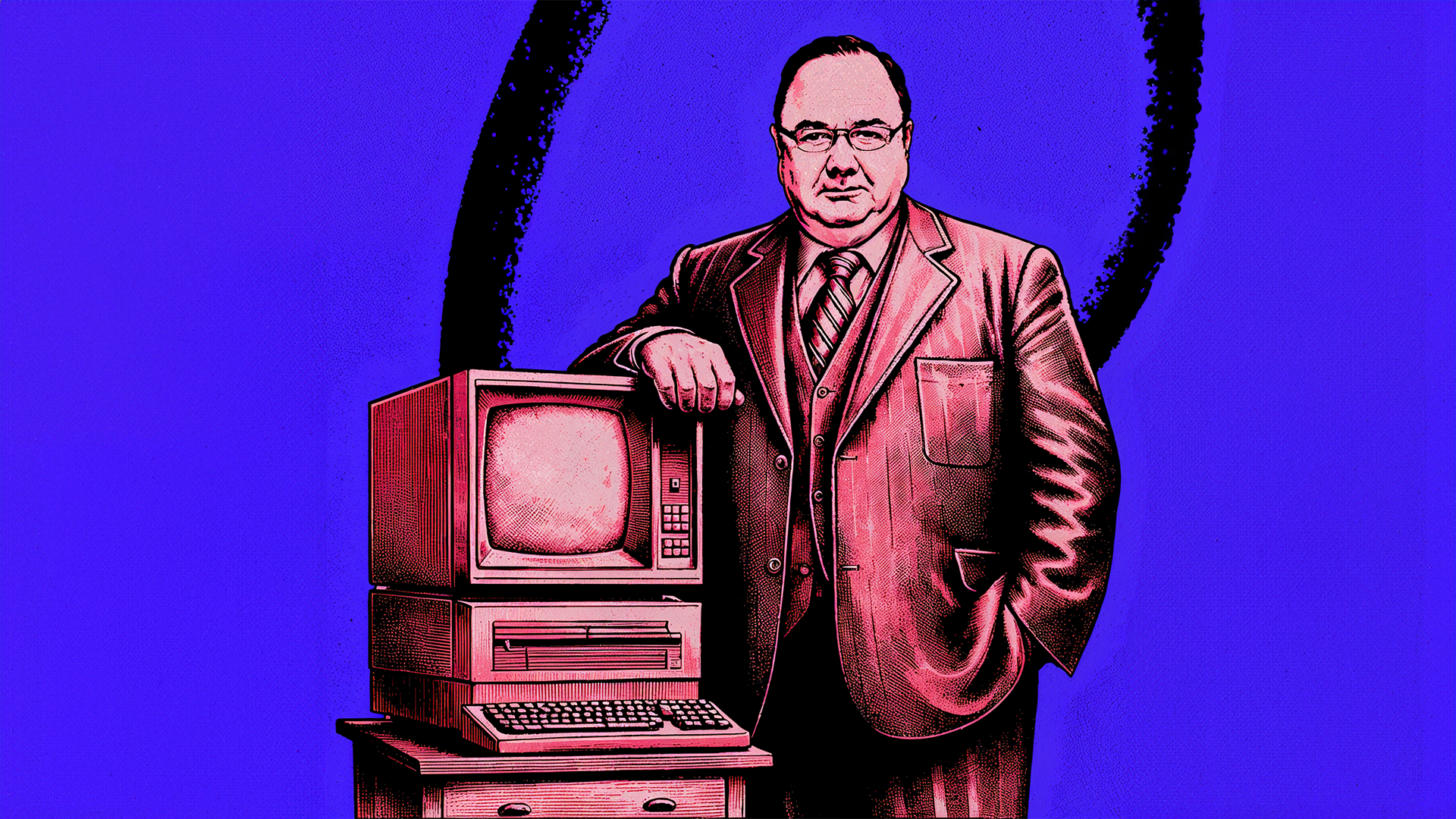

The Secret Father of Modern Computing

How Ed Roberts created the personal computer industry—and then walked away

We’re in the midst of the biggest paradigm shift in technology since the internet and the personal computer. If you want to understand what’s going to happen with AI, you have to understand how previous technology shifts played out—because history repeats itself. That’s why we’re publishing this original essay by digital strategist and historian Gareth Edwards on the secret history of the first PC revolution. It's a long read with which to settle into the weekend. We hope it sheds light on the past—and on the future. We’d like to publish more of these pieces by Gareth, so if you like it, please let us know. —Dan

In September 1974, Ed Roberts was sitting at the bank in a foreclosure meeting. His once-profitable calculator company, Micro Instrument and Telemetry Systems (MITS), had exhausted its $250,000 overdraft and was on the verge of bankruptcy. But Roberts wasn’t getting ready to shut down. Instead, he was soliciting a $65,000 loan. Not to spend on calculators, he explained to the bank, but for something completely different. Something nobody had done before. He planned to build an affordable personal computer.

The bankers were dubious. Everyone knew that computers were large and expensive, the domain of big business. “The banker asked me, ‘Well, how many of these do you think you'll sell?'” Roberts remembered later.

It was a question that he’d hoped they wouldn’t ask because Roberts had no answer. He had decided to pivot his entire company on a personal hunch: that he could sell a large number of low-cost computers in a market where most companies expected to sell four or five expensive ones every year. “I said, ‘I think we'll sell seven or 800 of them over the next year.’ [The banker] laughed at me, accused me of being a wide-eyed optimist and all that."

For a second, Roberts thought that this was the end of MITS. Instead, the banker sighed and signed off on the loan. He explained that he saw little value in foreclosing now. If, somehow, Roberts managed to sell even 200 of these machines, it would yield the bank some return.

Roberts went away surprised, but happy. This didn’t mean he wasn’t worried. His business depended on him being right about two things everyone insisted were wrong: that you could create a useful computer for less than $400, and that there were people who would buy it.

But Roberts had conviction. "Here’s the thing that’s so hard for people to understand now,” he said. “Those of us who wanted computers lusted after computers. That's the only way to describe it. The idea of possessing your own computer... I mean... wow. There were only one or two things more exciting about that. And I'm not even sure about them!"

We often picture tech disruptors as brash, dynamic figures who are keen to be both seen and heard. Yet the personal computing industry was largely sparked by a straight-talking ex-Air Force officer—one more Ron Swanson than Elon Musk. He ignored claims by IBM and others that people didn’t want a computer at home, and risked his whole company on a hunch that they were wrong. His approach to business was different from the “move fast and break things” model we’ve come to expect from tech entrepreneurs, yet he succeeded beyond all expectations because of it.

This is the story of Ed Roberts, the man who created the personal computer, launched the careers of Bill Gates and Steve Wozniak, and decided—at the height of his success—to walk away. It is based on archival video interviews with Roberts, Gates, Steve Wozniak, and many of the other key figures involved. I also draw on written accounts by Forrest Mims, Paul Allen, and others who were there; contemporary publications, such as Dr. Dobbs Journal and Popular Electronics; and books like Fire in the Valley and Endless Loop: A History of Basic.

Dreams of selling a computer

Roberts had started to act on his hunch about personal computers long before meeting with the bank. As early as 1972, as the power of microprocessor chips was increasing and their prices were dropping, he sensed that there was an opportunity to produce a mass-market computer. He also understood that the electronic calculator market in which MITS had enjoyed great success was about to implode.

Like most of the firms that had ridden the calculator boom, MITS made very few parts itself. The company designed the boards, selected the chips, sourced the parts, and (for an additional fee) would even assemble your calculator for you. However, as demand grew, chip manufacturers started entering the market, and companies like Texas Instruments began to sell directly to customers. They could offer cheaper products than third-party assemblers like MITS. Almost overnight, Roberts’s profit margins disappeared.

Roberts wanted to exit the calculator market entirely—and he had experience making bold decisions. Initially, MITS made electronic telemetry systems for model rockets—hence, its full name, Micro Instrument and Telemetry System, which was cleverly selected to create a mental association with MIT, the university. After several years catering to rocket enthusiasts, Roberts had sensed that the market for electronic calculators was about to explode. When his founding partners in MITS proved reluctant to pivot, Roberts offered to buy them out. After they accepted, he took the company successfully into the calculator market. As far as he was concerned, pivoting to affordable computers was a natural progression from pivoting to affordable calculators.

"I know now that I'm onto something good when everyone else thinks it’s a bad idea,” he said. “I just didn't figure that out until later."

Roberts’s interest in computers was different from most of the customers who would eventually buy his machine. He was a realist—fascinated by what they could do now, rather than the future they represented. In fact, he had always wanted to become a doctor, but he grew up in a relatively low-income family, so he had to find a way to pay for college. He chose to study electrical engineering and committed to a period of service afterward with the U.S. Air Force (USAAF), which ensured that his tuition would be covered. After graduation, he joined the USAAF Weapons Lab at Kirkland Air Force Base near Albuquerque. Some years later, he created MITs along with other Air Force personnel.

At college and Kirkland, Roberts had encountered some of the most powerful computers then available. He was fascinated by computers—how they could democratize power, and who they could offer that power to.

“To some extent, your worth has always been measured by the number of people you control—the number of people you ‘own,’ so to speak,” Roberts explained. “In the case of the computer, one person can do the work of thousands. So by any historical definition, if you have a computer, you’re wealthy. I mean, wealthy beyond all imagination. That’s always intrigued me about computers. The enormous amount of power it gives us regular folks.”

Negotiating an affordable chip

In his quest to pivot MITS to computers, Roberts found an ally in Bill Yates, an Air Force veteran who’d worked alongside Roberts at Kirkland. Yates was a talented electrical engineer. When Roberts had needed to buy out his MITS co-founders, Yates stepped in to help. He partially funded the purchase in return for a share of the company.

Roberts and Yates watched as the microprocessor market developed. At the time, the processing power of most available chips was low, which limited their potential usefulness for real-world applications. The National Semiconductor IMP-8 and IMP-16 microprocessors required extra hardware to run, rendering them unusable on a cost basis. Another possibility was the Intel 4004 or 8008 chips. However, the duo soon realized that they weren’t powerful enough to create a fully programmable machine. There were rumors that Motorola was working on a solid microprocessor, but that’s all they were—rumors.

By the beginning of 1974, both men knew the window to save MITS was shrinking. The company was in the red and was down to fewer than 20 employees. It was then that they enjoyed a moment of luck.

Roberts had cultivated a strong relationship with Intel, from which he regularly sourced calculator chips. He mentioned to MITS’s Intel rep that they were hunting for a microprocessor with which to build a home computer. The rep took Roberts and Yates into his confidence and confessed that Intel had an unannounced microprocessor that was almost ready—the Intel 8080, which was a major improvement on the 8008. He suggested that it might be powerful enough to meet their needs. He also secured them early access to the 8080’s data schematics, as well as some samples. Roberts and Yates immediately recognized that the 8080 was exactly what they had been searching for.

Roberts’s straight-talking approach with his suppliers and financial backers occasionally created problems for MITS in the cut-throat calculator market, where overpromising and under-delivering were routine. But it also resulted in a level of trust with MITS’s partners that few other companies enjoyed. This had already landed the company early access to Intel’s new chip. Now it proved its worth financially as well. Intel planned to sell the 8080 microprocessor for $360 a unit. It cost the company barely a fifth of that to manufacture them, but it correctly believed that the majority of its customers—computer firms manufacturing machines that cost tens of thousands of dollars—would pay the high price.

Roberts, however, was a veteran of the brutal price wars over calculator chips. He knew that Intel’s sales team liked the security that bulk orders offered them, so he took a gamble. He told Intel that MITS was prepared to order 8080 microprocessors in batches of 1,000, at a minimum. In return, he wanted a massive discount. Intel agreed to a much lower price of $70.

This deal was a game changer. It made MITS’s plans to sell a personal computer that retailed below $400 viable—an impossibility if $360 of that budget went to the microprocessor. Armed with the new deal, Yates began designing circuit boards for a computer based on the 8080, while Roberts created the logic interface—or series of instructions—that would allow their new microprocessor to work with up to 256 bytes of memory and a 2MHZ clock. (This may not seem like much now, but it would make the machine almost as powerful as the computer that had landed Apollo 11’s astronauts on the moon a decade earlier.) It was enough that a home user with enough time and creativity could program the machine to do genuinely useful things.

During the design process, Roberts realized that customers might come up with ways to use the new computer that he hadn’t considered. In what would prove to be a revolutionary decision, he built sockets that would allow peripheral cards to expand the machine’s capabilities. In doing so, he created the open architecture philosophy on top of which much of the computer industry innovated.

Media coverage wars ensue

By June 1974, with the last of its cash reserves almost exhausted, MITS was close to having a workable computer. But the company had not yet worked out how to let its potential buyers know it existed.

One day in July, Roberts got a phone call. “Ed! It’s Les Solomon,” came a cheerful voice. “You’ve still got that 8080 project going on, right?”

“We do.”

“Great. Then I’m coming to Albuquerque.”

Throughout the seventies, two electronics magazines were waging a war for readers: Popular Electronics and Radio-Electronics.

Les Solomon was the technical editor at Popular Electronics. He’d first met Roberts in the summer of 1970. Forrest Mims, an ex-Air Force engineer, had been writing for the magazine under Solomon. One day, while Solomon was visiting Mims in Albuquerque, Mims insisted that he meet a local friend—Mims’s former business partner.

Solomon found himself in a steakhouse later that night with a tall, broad-shouldered man with a military air. This was Ed Roberts—it turned out that Mims was one of the original co-founders of MITS. “Ed had this idea about offering an electronic calculator kit,” Solomon later recalled, “And, well, I had to listen since he stands over six feet and weighs 235 pounds or so!”

Solomon thought that the idea was a good one. Popular Electronics would run a cover story on the calculator. In return, Roberts would write an assembly guide exclusively for the magazine. The feature was a hit with readers. Roberts became someone Solomon could turn to if he needed an expert in a hurry, and he spent the next few years writing for Solomon whenever the need arose.

In the spring of 1974, Solomon and Art Salsberg, Popular Electronics’s editor in chief, became convinced that they needed to feature a computer on the cover to boost sales over their rivals at Radio-Electronics. Solomon started looking for projects that might fit the bill. He learned that Roberts was working on an 8080 microprocessor machine. The idea sounded promising, but MITS didn’t have a working prototype yet. Instead, Solomon turned to Jerry Ogden, another contributor who had created a machine using Intel’s existing 8008 chip. It was simpler than Roberts’s idea, but it already existed.

In July 1974, as Solomon was working with Ogden on the Popular Electronics piece, the latest issue of Radio-Electronics hit newsstands. Its cover featured an 8008 machine called the Mark-8. It was too simple to qualify as a computer, but it was easily a match for Ogden’s machine. Popular Electronics had been beaten to the punch. “I felt as though the rug was pulled out from under me,” Salsberg later wrote.

He called Solomon into his office and asked if he knew of anyone working on something better, ideally using the 8080 chip. Solomon mentioned Roberts. Salsberg said that if Roberts could get them a machine and article by December, he would turn over the magazine’s January 1975 cover to this new computer. This was a big offer—the January issue was the best-selling issue each year.

“Tell him that he’s got to have an attractive cabinet in order for it to be a cover story,” Salsberg shouted after Solomon. Salsberg knew that the machine needed to look as good as it sounded, so it needed an impressive case. Solomon went to call Roberts to give him the news. He told him that as long as MITS could get a working version of its machine to the Popular Electronics offices in New York by the end of October, the cover would be theirs. Roberts agreed to the deal. The race to create a working machine was on.

A cover photoshoot, with mishaps

In October 1974, Roberts, Yates, and Jim Bybee—one of the dwindling number of staff still at MITS—finished the prototype for the world’s first personal computer. Roberts, never one to worry about names for his machines, christened it the PE-8. The company was running on fumes, propped up by the emergency loan from the bank. Roberts didn’t care. They had hit Art Salsberg’s deadline. Now, all they had to do was get the PE-8 to New York so Salsberg and Solomon could see that it existed.

“We were gonna die if this article didn’t go. We were dead,” Roberts recalled later. “So I sent it by Railway Express/Air Express, which was a sort of UPS of the time. I figured that would be the safest way. Even sent it Priority… I got on a plane to get out there, after we’d loaded it up… guess what day Railway Express decided to go bankrupt?”

While Railway Express had yet to go bankrupt, a series of strikes erupted in October 1974 that brought shipping to a standstill. Upon arrival at John F. Kennedy International Airport, Roberts discovered, to his horror, that his only working computer was lost in that chaos. “I figured we were dead now,” he said.

Still, Roberts went to his meeting with Salsberg and Solomon. He had the schematics and functional diagrams in his luggage. All he could hope to do was persuade the magazine’s editors that MITS wasn’t bluffing, and that Popular Electronics should stake its reputation on a machine its editors had never seen.

To his surprise, they agreed. “I think they trusted that we had done enough projects together,” Roberts said later, still with a hint of astonishment in his voice. “And because we’d always done what we’d said we do, they trusted us. They said ‘Okay. If you can send us something we can photograph, we can go with that.’”

When Roberts returned to Albuquerque, he got another phone call from Solomon. This time it was about the name. PE-8 just didn’t sound very exciting. Would MITS consider calling it something else?

“I don’t care what you call it,” Roberts told him bluntly. “But if we don’t sell 200, we’re doomed.”

Solomon suggested “Altair,” a word his daughter had heard during an episode of Star Trek. Roberts agreed. MITS pulled together a dummy case, rebranded it Altair 8800, and shipped it to New York for a photo shoot. Luckily, this one arrived.

“It was an empty box,” Roberts told an interviewer later, laughing. “The lights came on, but that was about it.”

Even before the story was published, Roberts began to suspect that they might be onto something with the Altair.

In November, a man named Roger Melen visited MITS offices. He came from Stanford University and begged to be sold a machine. He’d been in New York to submit a story to Solomon on a prototype digital camera, and had seen the Altair mockup in the Popular Electronics office. Rather than fly back to California, he’d decided to come straight to Albuquerque. Roberts agreed to ship Melen the first production machine: it would be the third off the production line after the now-lost test machine and the one MITS was keeping for itself.

Roberts’s empty box had already started to change the world.

Gates, Allen, Wozniak, and more flock to the Altair

The January 1975 issue of Popular Electronics was published in December 1974. On the cover was the dummy Altair 8800, alongside the headline: “World’s First Minicomputer Kit to Rival Commercial Models.”

Within minutes of hitting newsstands, the phones at MITS were ringing. “And by the second week in January,” Roberts said, “we were already taking 200 orders a day.”

At the time, Bill Gates and Paul Allen were studying at Harvard University. In their spare time, they were trying to get a company known as “MicroSoft” off the ground.

“We were walking through Harvard Square, and saw this Popular Electronics magazine,” Bill Gates said. “And here was someone making this computer around the 8080 chip, in exactly the way Paul had talked to me about. And it was happening without us… we wrote to this company immediately and offered to do [programming language] BASIC for them.”

Their timing was fortuitous. If the computer was to be truly useful, it needed a human-readable programming language that ran on it, not just raw, binary computer code. Yates, who had highly technical users in mind, had been trying to convince Roberts that a sophisticated scientific or mathematical programming language would be best for the Altair. Roberts disagreed. He wanted something that anyone could use.

BASIC fit that bill perfectly. It lacked some of the high-end functionality of its rivals, but this was deliberate—BASIC was created in 1963 for non-technical users. By making BASIC the language of the Altair, Roberts could stay true to the idea that the machine was one designed for “regular folks.”

Roberts and Allen spoke over the phone. Roberts told the young software engineer that many people had promised him a version of BASIC for the 8080 chip, but nobody had shown him something that worked. The first person to do so would get the job.

A month later, Allen landed in Albuquerque, wearing a borrowed suit and clutching a paper copy of the code necessary to run BASIC on the Altair. Allen and Gates had written it in a flurry. Allen called MITS and told a surprised Roberts he was there. Roberts drove to the airport himself to pick Allen up.

Contrary to popular belief (and even Microsoft’s official history), the version of Altair BASIC that Gates and Allen created did not run perfectly the first time. When it reached the command prompt, the program crashed. Allen was horrified. He thought they’d blown their chance. He called Gates, and they debugged it over the phone. Allen asked Roberts for one more shot. Gates was already rewriting the code, which would be rushed by priority mail to Albuquerque.

Roberts agreed. Because it was already late, he drove a protesting Allen to a nearby hotel. It was there that the developer confessed he didn’t have enough money for a room. Amused, Roberts handed Allen his own credit card and said he’d retrieve it the next day. Although Allen and Gates didn’t know it, they’d already impressed Roberts by getting as far as they had, and he had already decided to offer them jobs. When their code ran without error the next day, that only confirmed his decision. Within weeks, Allen was MITS’s new director of software. Gates dropped out of Harvard later that year and joined MITS, writing new versions of BASIC and other software for the Altair.

Gates and Allen weren’t the only ones inspired by the Altair. In California, the Popular Electronics story spurred Gordon French and Fred Moore to found the Homebrew Computer Club—a regular meetup in which professionals and amateurs could share their knowledge of computers.

Thirty-two people turned up at the first meeting in March 1975, which took place in French’s garage. Half worked in mainframe computers, several were from university departments, and a smattering were musicians, engineers, and other dreamers who thought that they would never get another chance to play around with a proper computer after graduating from college—let alone own one.

And there, on the table in the middle of the garage, was an incredible sight—one of the only Altair 8800s in existence at the time, the Altair #3. It had been shipped to Homebrew Computer Club member Roger Melen.

Seeing the Altair was a near-religious experience for one of the attendees. “It was that day, the first day of Homebrew Computer Club, that I realized, finally, I can have the computer I wanted,” a young engineer named Steve Wozniak remembered. “I was too scared to say anything. I’d been spending my time designing calculators for Hewlett-Packard. I’d gotten out of computers. But they gave me a datasheet. They passed out datasheets! I took it home and said, ‘Oh my gosh, this is like the computers I used to design back in high school!’ So I was back in business.”

Wozniak, inspired and empowered by the Altair, created the first Apple computer later that year. After meeting fellow enthusiast Steve Jobs at the Homebrew Computer Club, they decided to go into business together.

Roberts makes his exit

Roberts had hoped his computer would sell well, but the demand was well beyond anything he could have predicted. The sheer variety of uses caught him by surprise.

“The very first call I ever took for an Altair was from a dentist in Chicago,” Roberts later said. “He was president of a model train club. They wanted to use an Altair to control their model train layout.”

By the end of February 1975, two and a half months after launch, MITS had gone from having a $250,000 overdraft to more than $250,000 in the bank. By August, the company had shipped over 5,000 machines—and that was barely making a dent in its outstanding orders. Roberts’s hunch had been correct. The result was an entirely new industry: personal computing.

In 1977, with MITS registering sales upwards of $6 million (roughly $32 million today), Ed Roberts sold MITS to a microchip and motherboard supplier called Pertec Computer Corporation. And then he walked away.

“[Ed] was utterly confident his entrepreneurial gifts would allow him to fulfill his ambitions of earning $1 million, learning to fly, owning his own airplane, living on a farm, and completing medical school,” Forrest Mims remembered when describing his good friend later.

Roberts had achieved the first three. Now, the thought of finally mastering the last two—owning a farm and securing a medical degree—had entered his mind. And because he’d come within a few weeks of losing everything, he knew the importance of cashing out while the going was good. On top of this, the personal computer industry he had created was changing—and he wasn’t sure he fit in.

In style and personality, Ed Roberts was different from the other figures at the forefront of the computing revolution. He was a gruff ex-Air Force officer with a strong sense of honesty and honor, and he wasn’t fond of excess or the limelight. When he picked up Paul Allen at the airport, it hadn’t been in a fancy car or slick suit. Roberts had been in his pickup truck wearing a plain shirt and tie.

Even in 1977, Roberts could read the writing on the wall. The moment he’d proven that there was a demand for personal computers, big personalities and big-money businesses started to move in. He’d already sold a controlling interest in MITS to Pertec at the end of 1976, agreeing to stay on to run its special projects division. In this role, he saw Paul Allen and Bill Gates move to secure the IP rights for the Altair version of BASIC from under the company, claiming they had always belonged to Microsoft. Roberts believed that this was dishonest and a fundamental breach of trust. He knew what he’d paid for and signed off on, and this soured the relationship between him and his former proteges for years to come.

In late 1977, Roberts revealed the new product his division had been working on to the Pertec-run MITS management: a computer that wasn’t only portable but could be used on your lap. Roberts had another hunch, one that said portable computers was another market waiting to explode. The new management told Roberts that there was no interest in a lap computer, and that there never would be. They declined to pursue it.

“I guess consider this my resignation then,” he told them, walking out of the door at MITS and away from a role at the forefront of the industry he had created forever.

A resolution with Gates, and a conclusion

In early 2010, hospital staff in Macon, Georgia were stunned when a man recognizable across the globe walked into their hospital.

It was Bill Gates.

Gates asked to be pointed in the direction of a specific patient, one best known in Georgia as a beloved rural doctor. One who never turned away a patient, even when he knew they couldn’t pay, and who’d treated AIDS patients for decades, even when fear and prejudice had seen other practices close their doors. He was a doctor who had been elected to medical honors society Alpha Omega Alpha in recognition of his contribution to rural medicine. At 68, he was losing a battle with pneumonia, one that would soon take his life.

The man was Dr. Henry “Ed” Roberts.

After walking away from the industry he helped create, Roberts moved to Georgia and returned to college. He studied to become the doctor he’d always wanted to be. He never hid his past in computers. In his medical office, there were two Altairs proudly on display. If asked, he’d talk about the role he’d played in creating them. He continued to dabble in computer programming and system design on the side. However, most people in his hometown of Cochran, Georgia only knew him as a doctor.

Some years before, he and Paul Allen had resolved their differences. Allen had even arranged for Roberts to be interviewed as part of a computer history project for high school students. He felt there were few better examples of computing pioneer role models.

Many of the quotes in this piece come from those interviews, in which Roberts was his usual, candid self. He was asked what advice he would give to teenagers who hoped to make their way in business and technology.

“The most important thing is to be honorable, and kind of work from there,” he replied. He spoke about the various times MITS had come close to failure, only to be saved by the blind trust placed in him by others. “If you have integrity, that makes up for a lot of things. A lot of inadequacies. I never lied to anyone. I always told them exactly what the situation was and what we could do to get out of it. That’s true for life in general as well. Don’t lie to yourself.”

Bill Gates’s relationship with Ed Roberts remained cold for some time. Roberts always believed Gates had betrayed his trust when it came to the ownership of Altair BASIC. He also felt Gates had lied on the stand during the IP dispute over it, and had acted in a way that didn’t conform to his principles on how business should be done.

But Gates had heard from their mutual associates that Roberts was seriously ill. This was likely the last opportunity they’d have to talk. So he’d hurried to Georgia to visit his old boss one last time. We’ll never know what words, if any, passed between them—whether a final rapprochement was reached between the honorable old engineer who had created an industry and the brash, young software developer who went on to conquer it.

Asked once about his legacy, Roberts said he had a hunch that neither he—nor the Altair—would be remembered in the end, and that he was fine with that. The people who he felt mattered knew what they’d achieved.

“I guess it will be interesting to see what the history books say,” he said. “But I think a lot of what we did with the Altair will be lost. Because that was a giant step to go from nothing to the Altair. And after that, well… when you get something to work from, it all seems a lot easier.”

Ed Roberts died on April 1, 2010. Outside of the technical press, the death of the man once known as the father of modern computing passed mostly unnoticed. The media at the time was talking excitedly about the launch of Microsoft Windows Vista and the new MacBook Pro.

Roberts’s final hunch was right. The world had moved on.

Gareth Edwards is a digital strategist, writer, and historian. He has worked for startups and corporations in both the UK and U.S. He is an avid collector of old computers, rare books and interviews, and abandoned cats. Follow him on X, Mastodon, and BlueSky.

Find Out What

Comes Next in Tech.

Start your free trial.

New ideas to help you build the future—in your inbox, every day. Trusted by over 75,000 readers.

SubscribeAlready have an account? Sign in

What's included?

-

Unlimited access to our daily essays by Dan Shipper, Evan Armstrong, and a roster of the best tech writers on the internet

-

Full access to an archive of hundreds of in-depth articles

-

-

Priority access and subscriber-only discounts to courses, events, and more

-

Ad-free experience

-

Access to our Discord community

Comments

Don't have an account? Sign up!

Very nice piece of writing. I knew the Altair started it all yet I knew very little of this story. Thanks!

This was great! Lots of great detail presented in a breezy way. More like this, please!

It was written beautifully , thank you for taking the time to share this hidden history peace with us .Yahli

Wonderful! I was in Albuquerque decades later, and recall a local foreign car father and son shop, who recalled some of these people, and their drive and dreams.

And the old huge computers and horrible stacks of punched cards. Cold cold cold chilled non ilitary computers… starting to get me and other students to “ think” computer in business settings.

Thanks.

Always great reading about the history of the industry. Really great article!!

As someone in tech, this was just an amazing piece to read and rather makes me ashamed that I did not know it myself.

My wife and most of her family are Cochran, Georgia natives. Ed was my wife's mother's doctor. Ed was a great doctor, extremely caring, and modest about his technical achievements. Hardly anyone in his small town knew of his significance in computer history. Early personal computers, such as the Altair, inspired me to later become a computer scientist.

Amazing writeup! Really takes you along.

Over the last couple of days I read all The Crazy Ones stories. So well written - thank you Gareth!

great piece!

Wonderful and inspiring story. Thanks for this delight