Why Interest Rates Matter (and Which Rates Matter)

Where interest rates come from, why they exist, and who they impact the most

March 27, 2023

People tend to sum up Arnold Schwarzenegger’s career progression like this: He became a bodybuilder, later became Terminator, and eventually became the governor of California. And while those waypoints sound rather discontinuous, it’s pretty easy to see how they connect. He leveraged his marble-sculpted biceps to stand out for acting roles fit for enormous men, and then leveraged the resulting fame to become governor.

But to assume that his riches were generated entirely by leveraging the body he built and the fame he accrued from it would be inaccurate. Arnold was a millionaire before his acting career really kicked into gear, and it wasn’t winning bodybuilding competitions, product endorsements, and contracting work that made it happen. He chose to parlay his earnings into a bet on inflation and interest rates.

That may sound opaque, but it’s really not all that complicated. In the ’70s, Arnold started buying apartment buildings with mostly borrowed money, and inflation pushed up the price of the real estate (good) while reducing the real value of the loans (extra good). It turns out that his roles in movies and politics are less career progression waypoints and more fun side hustles for a real estate investor.

As you can imagine, interest rates matter to more people than just Arnold. They’re the price of money over time, so they affect the payoff of literally every decision you make that involves doing something now with the expectation that it will affect your future.

Interest rates matter the most for two diametrically opposed kinds of businesses:

- Highly levered, capital-intensive old economy firms like real estate, oil, and gas, heavy manufacturing, airlines, etc.

- High-growth, future-focused companies that are typically asset-light and that have most of their expected profits in the distant future.

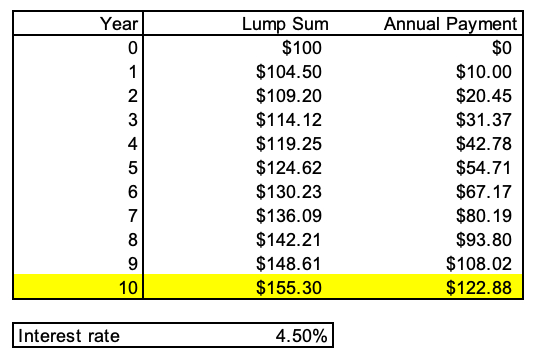

To understand why interest rates matter the most for those businesses, you need to understand two different mechanisms and to understand those mechanisms, you first need to understand one simple concept: Giving me $100 today is more valuable to me than promising to give me $10 every year for the next decade. After all, if you have the $100 now, you can invest it and end up with more than $100 at the end of a decade.

The return you get on that investment determines the cost of having money later rather than now.

In order to make up for that value difference, lenders require borrowers to pay interest, expressed in terms of a rate. The rate of choice is always higher than the risk-free rate, which is effectively the rate that the Federal Reserve charges (this is where monetary policy and treasury bills enter the scene, but we won’t get into that for now). Since investors want to make money from their investments, the rate they charge is based on the expected returns and perceived risk of the investment.

Okay, now let’s look at the mechanism that impacts highly levered capital-intensive old economy firms: the price of borrowed money.

The monthly payment on a $450,000 house bought with 80% down today will be $2,330 at the current average interest rate of 6.73%, versus $1,453 for a house bought at the same price with the same loan at the median 30-year rate that prevailed at the end of 2020.

Obviously, low rates are favorable for homeowners.

Now let’s look at the mechanism that impacts high-growth future-focused companies: the present value of distant future profits.

Typically, investors calculate that present value based on the rate they can expect to gain from risk-free assets over a similar duration—if you’re estimating the ROI on a marketing campaign for a subscription product where subscribers stick around for an average of four years, you’d compare those rates to treasury bonds with similar maturity, whereas if you’re thinking about the return on investment for building a new office building that could be in use half a century from now, you’d use a longer-term rate. Then they discount the value of future profits back to the present. The rate at which they discount those profits is always higher than the risk-free rate because investors reasonably demand to be paid a premium in exchange for taking risks.

Consider a biotech startup planning to spend $50M/year for the next five years, after which it will start earning profits of $200M/year from a new drug. (We don't actually know what these profits will be, or what the odds of FDA approval are, but we can hold both of those constant—the impact of interest rates on future profits will be proportionately the same regardless of whether we're talking about a 50/50 shot at $400M/year or a 10% chance of earning $1B/year. And the valuation of the company already reflects the market's consensus about what the odds-adjusted profits from the drug will be.) If the Federal Reserve is lending money, in the form of 10-year treasury notes, at a rate of 0.55% (the low in the summer of 2020), and the investor demands a 9% premium, then the present value of these future cash flows is $792M.

If you ran the same calculation at the current 10-year rate of 3.83%, the value drops to $536m. A third of the value is wiped out, entirely because of rate changes! That’s not something a startup founder would be fond of.

And it gets worse, annoyingly: If you break those present values into the present value of the losses compared to the present value of future profits, you'll find that the losses are less sensitive to rate changes because they occur in the near future: The present value of losses drops 8%, from $191M to $177M. But the present value of future profits drops by 28%.

In other words, a higher-rates environment is an environment in which growth investors have more confidence about what a company's efforts will cost and relatively less confidence about what those efforts will produce. In fact, if the upfront costs are high enough, and the profits are far enough in the future, an increase in interest rates can flip a project from being net profitable to net unprofitable, without changing any of its other fundamentals.

And there are other phenomena downstream of rates.

When startups can raise less, they spend less. And that means that growth at companies that sell to growth companies see not just lower valuation multiples but lower revenue growth, too.

If rates were set entirely in accordance with the whims of the average investor, they'd be very low all the time. And, as a consequence, we'd either have high inflation (if the interest rate you pay is less than inflation, you're effectively getting money for free) or a tight fiscal policy to compensate.

Rates are incredibly hard to predict, and people can have prosperous, well-paid careers from having just a slight edge in knowing where they're headed. So the average person should generally treat rates as a kind of random input into their decisions. But that doesn't mean to ignore them entirely: It means paying attention to how dependent you are on lower rates and what would happen if those interest rates changed. Interest rates apply to every asset out there, even in ways that are counterintuitive.

Back to Arnold: In the 1980s, when interest rates were relatively high, he helped create valuable franchises like the Terminator films. As rates declined, one effect of that was an increase in the long-term value of that intellectual property and a higher premium on movies that could spin off endless sequels. So Arnold’s first fortune came from paying low-interest rates at a time of rising inflation, but it turned out that his movie career was also a rates bet, and that one paid off, too.

About the author: Byrne Hobart writes The Diff, a newsletter about inflections in finance and technology with 48,000+ subscribers. Follow him on Twitter @ByrneHobart.

Find Out What

Comes Next in Tech.

Start your free trial.

New ideas to help you build the future—in your inbox, every day. Trusted by over 75,000 readers.

SubscribeAlready have an account? Sign in

What's included?

-

Unlimited access to our daily essays by Dan Shipper, Evan Armstrong, and a roster of the best tech writers on the internet

-

Full access to an archive of hundreds of in-depth articles

-

-

Priority access and subscriber-only discounts to courses, events, and more

-

Ad-free experience

-

Access to our Discord community

Comments

Don't have an account? Sign up!