Whenever a client wants to skirt the edges of copyright law, the usual response of copyright lawyers is: "Do you really want to find out?" That is...do you actually want to learn how much you'd owe in damages from copyright infringement?

I heard this a lot from lawyers when I ran a niche indie publisher. I suspect it's a refrain that AI companies are going to have to get used to as well. Many AI image-generators, like Midjourney, Stability AI, and DeviantArt’s DreamUp, were trained on copyrighted images.

In early 2023, the bill came due. Two parties—a group of artists (Andersen et al.) and Getty Images—separately sued AI image generators for copyright infringement. The lawsuits sparked discussion and debate among artists, engineers, VCs, AI companies, and the general public. I was surprised by how few people understood the nuances of copyright law.

I thought now would be a good time to write an explainer piece for the tech audience on the legal protections afforded to creative works. I’m not a lawyer, so don’t take anything here as legal opinion or advice. My knowledge is based on my personal experience, research, and consultations with experts.

Copyright: A (very) brief history, from pre-Gutenberg to post-Google

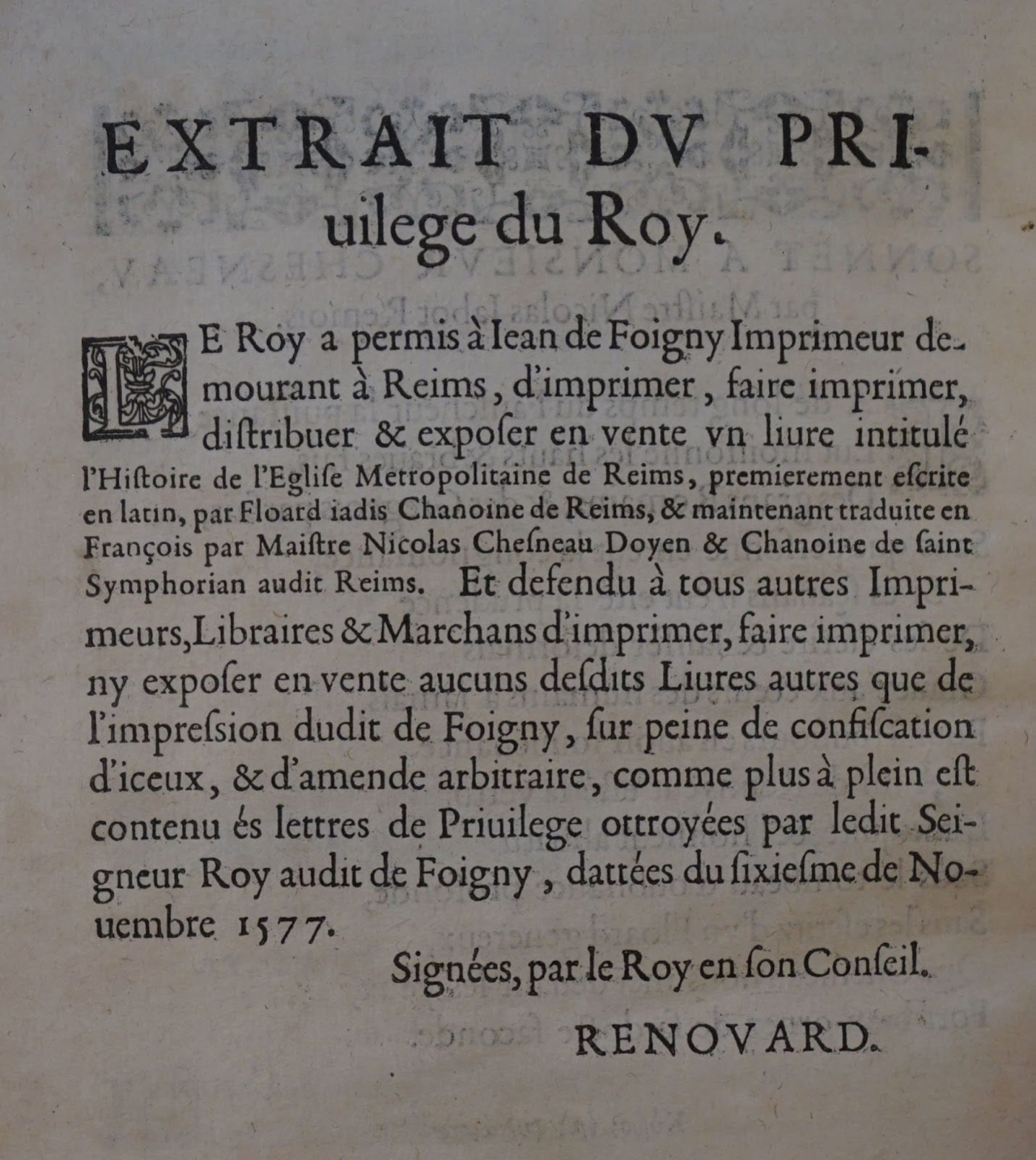

Copyright got its start in an unexpected place: royal courts. About 500 years ago, European monarchs began doling out privileges and licenses to their favorite artists. No one else but chosen creatives were allowed to publish and distribute works of art. In other words, the role of the writer/artist and publisher were often the same. These publishers’ exclusive rights to print and make copies came to be known as “copyright.”

A French royal printing permission from the 16th century granted publishing rights to a printing press in Reims.For a time, royally appointed publishers were the only ones who could afford printing presses. They adhered to and later enforced censorship standards because they were on the hook for what they printed. You published heresy or sedition? Jail time or the stakes for you.

Everything changed in the mid-1500s, after the rise of Gutenberg’s more affordable printing press. Suddenly, any priest or craftsman or gentle folk who got their hands on a press—by renting, buying, or partnering with an unlicensed publisher—could print whatever they liked. The roles of publisher and author started to diverge.

Pamphlets and flyers during the Gutenberg era were often anonymous. If writers were named, then often by informal agreements with their publishers, they could receive payments. Censor-publishers attempted to punish creators of unlicensed work, but they couldn’t keep up with printed seditions and heresies anymore.

Public opinion about royal copyright began to shift in the 1600s as English poet John Milton spoke out for the “liberty of unlicensed printing.” In what is now thought of as “the world’s first important essay in defense of freedom of expression,” Milton lobbied to free publishers from the tyranny of noble censorship.

Finally, the Copyright Act of 1710 passed in England. It was the first law to grant copyrights to authors. Ironically, it was a Hail Mary from the royal publishers who had failed to wrest back printing power from the masses. By giving authors an avenue for formal ownership, the publishing guild hoped to curtail unauthorized, unregulated publishing.

The birth of fair use in America

Because the 1710 English law didn’t apply to the American colonies, the U.S. had a late start in copyright. At James Madison’s suggestion, the Copyright Clause was written into the U.S. Constitution:

[The Congress shall have Power…] To promote the Progress of Science and useful Arts, by securing for limited Times to Authors and Inventors the exclusive Right to their respective Writings and Discoveries.

U.S. Constitution, Article I, Section 8, Clause 8, known as the Copyright Clause.

The 18th century had no TVs, movies, music recordings, photography, software, or the internet. So the rapid developments in technology and creative mediums resulted in 200+ years of legislation and litigation.

For better or worse, copyright evolved with the times. Early on, no one could reproduce work without the consent of the copyright owner, who would charge hefty licensing fees. That stifled public access to important information—like clips in TV news reports or educational content.

The Copyright Act of 1976 fixed that by introducing the concept of “fair use.” Some entities could use copyrighted materials for free under certain conditions. In lawsuits, courts would weigh many details to decide whether a reproduction was “fair use.” Here are a few examples (but by no means an exhaustive list):

- What entity copied the work

- The purpose of the copying (education, information, expression, etc.)

- How much of the original material was shared

- If the reproduction steals business from the original work

Initially, fair use was reserved for nonprofits and government entities. In recent years, courts started to grant allowance for commercial use if other factors were compelling.

Two cases, both featuring Google, highlighted that shift. In 2006, a Playboy competitor called Perfect 10 sued Google for indexing the magazine’s covers and displaying their thumbnails. In 2015, Authors Guild sued Google for scanning copyrighted library books and providing snippets of them in search results.

Snippet views from copyrighted book Rethinking Copyright on Google BooksIn both cases, courts ruled that Google’s search engine was a “highly transformative” use of the images and snippet texts. In other words, Google cataloged these artifacts for people’s research purposes, not entertainment. It was a unique enough application of the data to be considered fair use, “particularly in light of its public benefit,” as the judge on the Perfect 10 case said. A different judge on the Authors Guild case said something similar, granting the fair use of the books in part because it “augment[s] public knowledge.”

The concept of “transformative” use has been at the center of many copyright lawsuits in the past 30 years. It will play a big role in the current cases waged against AI image-generators. It’s not hyperbole to suggest that the future of artistic expression hinges on them as well.

What counts as "transformative" in copyright law?

So how much does a work have to change—in content or use case—to count as “transformative”? Unfortunately, the determination is subjective and there’s no clear line. Things are decided on a case-by-case basis in court, weighing the specific factors involved in each case. The legal precedents are ever-evolving.

Judges don’t just look at how much the purpose or use changed in reproduction. They also consider the content of the copying. Let’s explain with an example. In my eyes as a publisher, 50 Shades of Grey, by E.L. James, is a transformative work—a smutty retelling of the chaste teen romance Twilight, by Stephenie Meyer. James was inspired by Twilight, but she used different characters, worlds, story arcs, plot elements, and more.

50 Shades of Gray is so transformative of Twilight that most people who read the former never realize it was influenced by the latter. If Meyer sued for copyright infringement, it would’ve been a tough case for her to win.

Here’s where copyright law gets a little confusing. Although 50 Shades of Gray was in the clear, many other Twilight reproductions wouldn’t have been. The Twilight movies, for example, had to pay Meyer for the right to reproduce the series she created.

When creators adapt copyrighted material from one creative medium to another—film, books, musicals, songs, photography, translations, even sculptures and architecture—that reproduction is often considered a “derivative work.” If they don’t change enough aspects of the story, then they must pay licensing fees. This is the case even if the new work doesn’t make money.

Fan fiction falls in a gray area, and courts have ruled in different ways depending on the case. Fair use also protects many parodies, criticism, commentaries, and reviews (as does the First Amendment). Despite legal risks, transformative works are everywhere in our culture. But creators don’t have a definitive way of knowing if their use qualifies unless they get taken to court.

In AI lawsuits, the future of artistic expression is at stake

The concepts of “transformative” and “fair use” are at the heart of the lawsuits around AI image-generators.

In both cases, the plaintiffs are claiming that AI image-generators committed two wrongs. First, they used copyrighted images without permission while training the AI. Two, they produce derivative versions of copyrighted work. (Getty claims only some AI-generated images are derivative, whereas Andersen et al allege all are.)

The AI companies will likely defend their outputs as “transformative” and claim they are fair use. I don’t think the lawyers of Stability AI, DeviantArt, and Midjourney really want to find out how tall cash piles can stack when it comes to paying for copyright infringement damages.

Because this is the first copyright lawsuit against AI image-generators, it’s hard to know how the judges will rule. I’ve heard people complaining that the AI image-generators shouldn’t be subject to copyright because they create original images. As we’ve covered, that doesn’t necessarily protect a reproduction in the eyes of copyright law. It’s one small factor in the massive “fair use” mixing bowl judges must sift through.

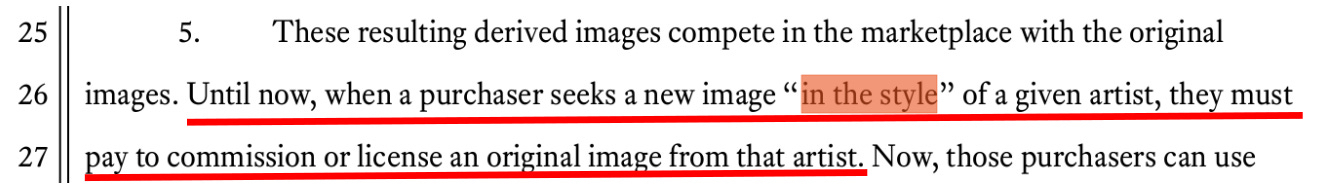

One of the plaintiffs goes even further in their lawsuit claims. The artists suing Stability AI argue that when the AI generators produce work “in the style” of an artist, Stability AI must pay to commission or license work from that artist.

Class action complaint from Andersen et al vs Stability AI et alIf the court accepted this claim, it could lead to future lawsuits from other plaintiffs looking for a similar payout. That takes us down a dark path for the future of artistic expression. If similar precedents were set, we could risk infringing on copyright anytime we take inspiration from others’ work. For example, whoever did the first Surrealist painting could theoretically try to collect damages from all Surrealist painters who came after.

I wish I could say Andersen et al’s lawsuit is overreaching, and judges are unlikely to decide in favor of it, but a recent high-profile case in music upheld a similar copyright infringement claim. A jury ruled that the songwriters of “Blurred Lines” must pay royalties and damages for copying the “feel” of a Marvin Gaye song (even though the lyrics and melody differed).

If we—and the courts—are not careful, we could begin to cede 500 years of progress on copyright with these types of precedents. Over time, copyright could regress to its original form: a way for the few chosen artists who “own” ideas to create monopolies and enforce their favorite forms of censorship. The creators who are left would have no legal means to publish and distribute their work. What a dystopian world that would be.

The ethics of using copyrighted data to train AI

Although this lawsuit could have far-reaching implications for all of us, I understand where the artists are coming from. My years running an indie publisher left me with a deep appreciation for the work of creatives, and I see their frustration and anger. The AI image companies have pushed the limits of copyright law for their own gain.

They should have sought permissions from copyright holders before using the data to train AI models. Midjourney’s CEO claimed that “there are no laws specifically about [harnessing copyrighted images for training].” Scraping publicly available data on the internet may not be illegal, but using that data to train AI models is a legal and ethical gray area—an open question if you will.

An open question does not mean: “Do what you want, without consequences.” Now the courts must decide if the whole operation is legal to begin with, and if using publicly available, copyrighted data to train AI is fair use. (AI raises many legal and ethical quandaries, and a few days ago the U.S. Copyright Office announced it would spend 2023 studying them.)

At the very least, AI companies should be giving attributions to artists. Even the most lax of creative commons permissions usually require that. It’s how artists make a name for themselves, amplifying their reputation. For the AI companies it would be an act of good faith, connecting us to the human behind the machine.

I also think AI-generated images should stay in the public domain for free, with no copyright, if they haven’t been modified by a person (so far, the government agrees). Machines and algorithms are not humans, so they shouldn’t get the creative protection rights that people do.

Where law ends and art begins

AI image and text generators are like the second coming of Gutenberg. His printing press put power in the hands of the public, and I hope AI tools will do the same. They’ll unleash profound social changes and help us unlock more forms of creativity—and along the way, pose legal and ethical quandaries.

If you’re still anxious about art and AI, just look to the French poet Charles Baudelaire’s concerns about photography in 1859:

“[T]his industry, by invading the territories of art, has become art’s most mortal enemy…If photography is allowed to supplement art in some of its functions, it will soon have supplanted or corrupted it altogether…”

Time proved Baudelaire partially correct: Photography has supplemented our art, but it’s never supplanted or corrupted us. May AI do the same.

Author's note: I'm in the middle of writing a series on AI's yet Unseen and under-explored impact on human society—and I'd love to hear your thoughts about AI and the human society! Let me know in the comments, or DM me on Twitter!

About the author: Helen Jiang has worked in agriculture, engineering, and geography, among other things. She is an entrepreneur and technologist, and writes about the Unseen at her Substack Earthly Fortunes.

Find Out What

Comes Next in Tech.

Start your free trial.

New ideas to help you build the future—in your inbox, every day. Trusted by over 75,000 readers.

SubscribeAlready have an account? Sign in

What's included?

-

Unlimited access to our daily essays by Dan Shipper, Evan Armstrong, and a roster of the best tech writers on the internet

-

Full access to an archive of hundreds of in-depth articles

-

-

Priority access and subscriber-only discounts to courses, events, and more

-

Ad-free experience

-

Access to our Discord community

Comments

Don't have an account? Sign up!

really good piece Helen and lots of this needs to be explored....have been teaching and writing about AI at Lehigh University for non-tech students since 2016, was selected to present to world journalism educators conference about how to do it in 2019 https://www2.lehigh.edu/news/rise-of-the-robots-coming-to-a-first-year-intro-to-journalism-class-near-you Dan has guest lectured in couple of my media entrepreneurship courses and if you ever want to talk about the issues we are thinking about see next comment. give me a holler. best Craig Gordon

Helen here are the issues I will be talking about with Lehigh alumni in our micro course in April:

1.Generative artificial Intelligence will give way to Transformative Artificial Intelligence within the next 5 years.

2. Another Artificial Intelligence winter is looming because we don’t have the tools yet to create the Consciousness part of Intelligence.

3. Leaving most development of Artificial Intelligence to corporations whose main purpose is pursuit of profit, leaves not enough resources to develop the UpperCase creative concepts needed

4. The best way to participate in new development products and services of Artificial Intelligence will be to use mathematical concepts such as Algebra, Geometry and Calculus with text, images and soon videos instead of numbers.

5. Anyone wanting to to become part of the Artificial Intelligence industry or discussion must first understand and know a definition of what Human Intelligence is.

Thanks for this detailed and thoughtful post. In addition to the question of copyrighted works as inputs to AI, will you be writing about how copyright law and patent law will affect the outputs of AI? This brief seems to indicate that AI outputs cannot be neither copyrighted nor patented:

https://www.polsinelli.com/publications/chatbots-select-legal-considerations-for-businesses

This seems like a big stumbling block for a lot of potential uses.