As the author Ryan Holiday’s research assistant, I’m worried about AI replacing me.

By most of the common psychological tests of intelligence, AI is smarter than me. AI can brainstorm more ideas than I can. AI can read a book, find information, fact check, and create content faster than I can.

So I’ve considered going back to working in coffee shops.

After I graduated from college, I chased winter. I lived and skied all over Colorado for the Northern Hemisphere’s winter months, and for the southern hemisphere’s, Australia and New Zealand.

To fund this year-round skiing, wherever I went, I worked part-time as a barista. When I think about my time working in coffee shops around the world, I find reasons to be optimistic about my job security.

Coffee shops around the world all have the same powerful machines. They’ve science’d most parts of the process—how the beans are grown, the mineral composition of the water, the milks and the drinkware. So, unlike not that long ago, you can get a great latte, cappuccino, or flat white basically anywhere.

Yet many people still love their drip coffee with half and half. Many love their cheap store-bought beans brewed by their countertop coffee pot. And many don’t care—they just want their shot of caffeine.

Coffee preferences are personal and abundant. The world is big enough for espresso machines and French presses. And which machine the barista uses depends on who they’re serving.

Art preferences are similar. So when I hear talk about how AI is going to replace artists, I think to myself, the world is big enough for both. Or when I see tweets about how AI wrote this “great” article or produced this “great” image, I ask myself, “great”—according to whom?

Countless authors, painters, and inventors who were considered ordinary in their own time are revered in ours. And anyone who has made and released creative work has experienced something analogous to making a delicious espresso for an audience that prefers a French press.

This is the perennial challenge of the artist: finding the middle of the Venn diagram where one circle is the artist’s tastes and the other is the audience’s tastes.

For the past two years, we’ve tried to hire another research assistant. We’ve trialed dozens of smart, creative, ambitious, book-loving, speedy fact-checking individuals. We always give them a version of the same assignment: read this book (usually a biography) and pull out two good anecdotes and two good quotes. What they come back with is not in the middle of that Venn diagram.

In a word, we’ve struggled for two years to find someone with taste—with an eye for what stands the chance of being interesting, entertaining, or useful to an audience.

We’re not alone. I’ve talked to authors, podcasters, documentarians, late-night TV writers, YouTubers and TikTokers, and they all share this problem. Most of these creators are actively or passively looking for people—whether researchers, writers, animators, video editors, producers, or production managers—with what Jerry Seinfeld identified as the ultimate skill of the artist: “taste and discernment.”

“It’s one thing to create,” Seinfeld said. “The other is you have to choose. ‘What are we going to do, and what are we not going to do?’ This is a gigantic aspect of [artistic] survival. It’s kind of unseen—what’s picked and what is discarded—but mastering that is how you stay alive.”

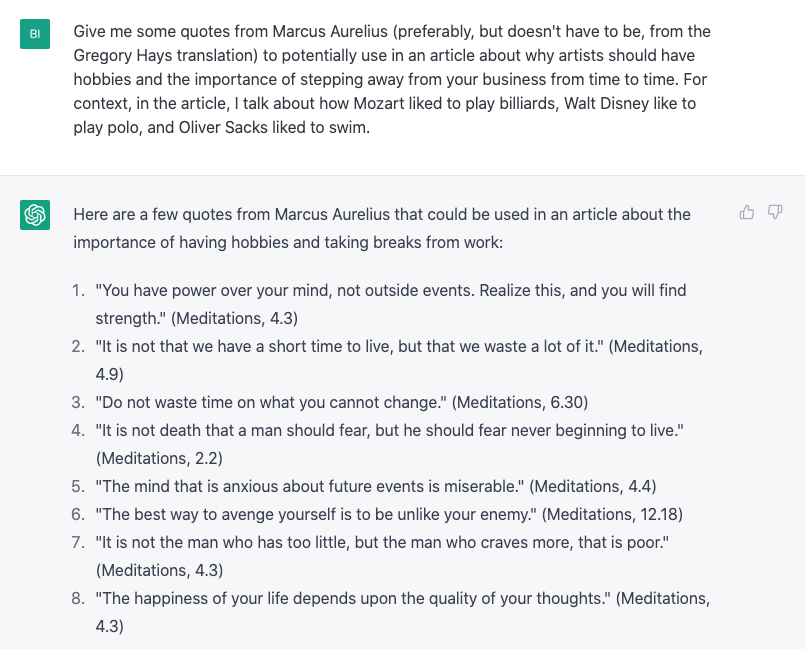

Tools like ChatGPT are great at creating. AI can generate options in high quantities at high speed. It is great at providing more choices. But it is not great at discerning and choosing what to do and what not to do. For example, I prompted ChatGPT:

The results are the worst we’ve seen. First, none of the quotes are relevant to the article I said I wanted to write. Second, none of the quote sources are correct. And third, none of the quotes are actual Marcus Aurelius quotes, let alone from the Gregory Hays translation (Ryan’s favorite, and the one from which we source for the Daily Stoic).

The tools will no doubt get better at pulling relevant quotes. But I’m less confident they’ll ever solve the perennial mysteries of taste and discernment. Many great artists have put out what they thought was their best work, only to see it flop. And vice versa—what they thought was average ended up going viral. Every time you release a work of art into the world, you can’t forecast its reception with any certainty. The best you can do is have a vague sense that others might like it. You (or the AI bot, or a hybrid of the two) are always guessing.

But if anyone is in a better position to make better guesses, I do think it’s humans.

When a work of art—whether a book or an album, a movie, a TV show, or a YouTube video—is well received, we say that it connected. The work connected with an audience—with humans.

To connect with humans, it helps to be among humans. Leonardo da Vinci kept a notebook hanging from his belt loop and, one of his contemporaries would recall, “went to places where he knew that people assembled and observed their faces, their manners, dresses, and gestures.” The filmmaker David Mamet used to ride the bus around Chicago, take notes of the things people said, and then go home and write dialogue. J.K. Rowling had the initial idea for Harry Potter on a Manchester-London train, wrote a lot of the series in cafes, and named some characters after childhood friends and based others on favorite teachers.

Artists who get so famous that they can’t go out in public talk about how not being able to do so makes it hard to create art that connects. To come up with material for Seinfeld, for instance, Seinfeld and co-creator Larry David liked to hang out in public settings where they could observe and eavesdrop on strangers. As the show became a cultural phenomenon, Seinfeld and David couldn’t go out in public like they used to. Strangers didn’t act like strangers around them. This slow detachment from humanity made it harder to make a show that connected with humanity.

When you don’t experience reality like most people do, it’s hard to make things that connect with most people.

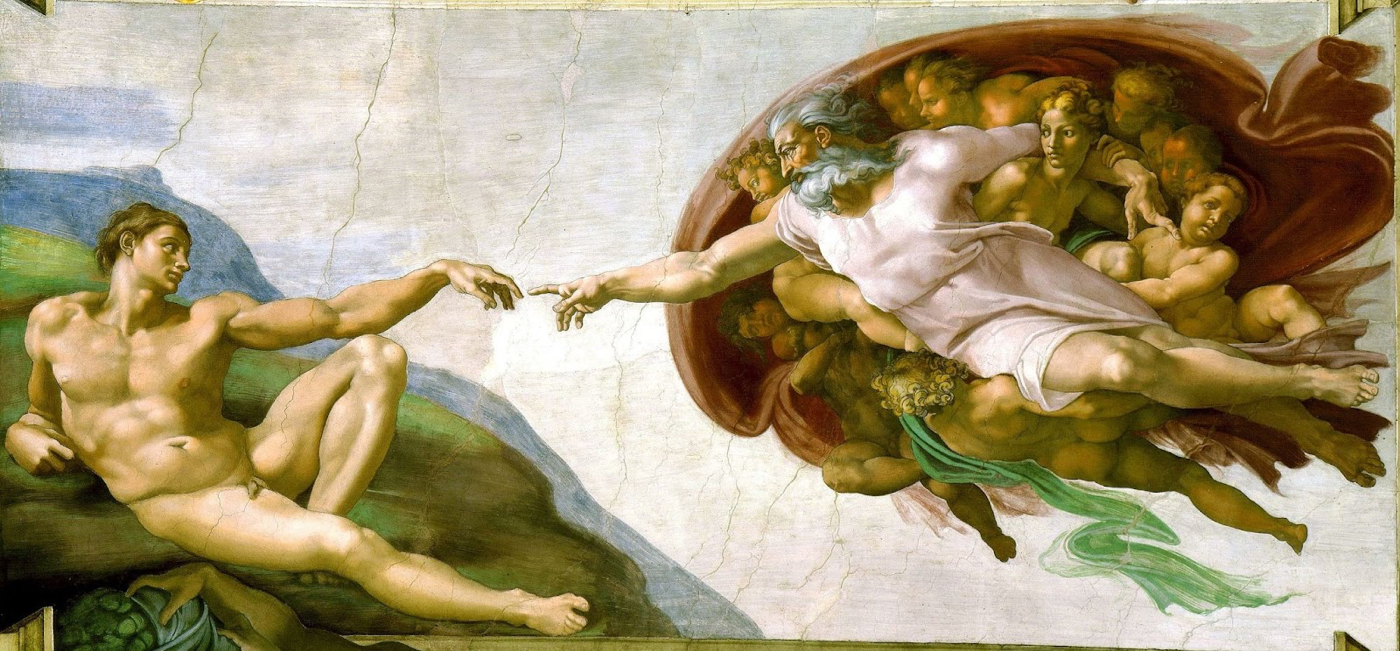

AI, completely detached from reality, will have a hard time making things that connect with people. It’s something of a hybrid between the Harvard grad student in the movie Good Will Hunting, who can regurgitate page 98 of Daniel Vickers’s Work in Essex County but can’t come up with any thoughts of his own, and Will Hunting, who can give you the skinny on Michelangelo—life's work, political aspirations, his relationship with the pope, sexual orientation—but can’t tell you what it’s like to stand in the Sistine Chapel and look up at that beautiful ceiling.

AI is smart. Ask it about books, and it can spit out a top-100 list. But it can’t tell you what it’s like to read a passage that puts perfectly something you’ve felt but couldn’t articulate. Ask it about music, and it can write you lyrics in the style of whoever you’d like. But it’s never listened to a great song, never heard one right when it needed to be heard. Ask it about taking a walk, and it can give you science-backed reasons to go for one. But it’s never been on a walk, never been totally excited by a thought or an idea that seemed to come from out of nowhere. Ask it about coffee, and it can give you an infographic that details tens or hundreds of brewing methods. But it’s never had that first sip of that first cup of the day. Ask it about connecting with an audience, and it can give you hundreds of best practices. But it can’t guarantee any of them are going to work.

It can’t be certain that your work (or its own) will connect with the human experience. It can’t be certain that the work will land in the middle of that Venn diagram. It can’t be certain that its taste and discernment are “great.”

This remains the perennial problem of making great art.

If AI solves it, well, I can teach you how to work an espresso machine.

Billy Oppenheimer is a research assistant who has worked with multiple bestselling authors. He independently writes the weekly SIX at 6 newsletter. Follow him on Twitter.

Find Out What

Comes Next in Tech.

Start your free trial.

New ideas to help you build the future—in your inbox, every day. Trusted by over 75,000 readers.

SubscribeAlready have an account? Sign in

What's included?

-

Unlimited access to our daily essays by Dan Shipper, Evan Armstrong, and a roster of the best tech writers on the internet

-

Full access to an archive of hundreds of in-depth articles

-

-

Priority access and subscriber-only discounts to courses, events, and more

-

Ad-free experience

-

Access to our Discord community

Comments

Don't have an account? Sign up!

Great stuff Billy - it will be thought and reasoning like this that will help guide us through this next era as AI becomes more integrated with our daily lives. Now, how about those espresso machine lessons?

I love this positive, realistic and moderate view of the place of AI in our future world. Thank you for that!

Still looking for that research assistant? I'd love to give it a shot. https://www.linkedin.com/in/apkoole/ ; https://ponytail.substack.com/

Hello! Thanks for such interesting ideas. But ChatGPT is trained on tons of documents, websites, etc. You can make your personal model by feeding it ONLY by Marcus Aurelius books, and letters. And the answer will be more accurate then.

Check out the discipline "neuroaesthetics". It might be of interest. AI will eventually know our tastes better than we do ourselves.

ever since i red about da vinci in robert green book mastery, i dall in love with him with his style and everthing about him what a man he was damn damn looking forward to red his bio soon