What does it mean to be strategic? Through my experience of leading engineering organizations at Google, both as a tech lead and manager, the word “strategy” and the need to “be strategic” came up a lot across technical, product, and organizational contexts. Yet clearly defining what either might mean and consistently delivering on both has been challenging.

As I understand it now, being strategic is a sort of practice, a thinking hygiene. Simply put, being strategic means that the outcomes produced by our actions are not at odds with our intentions.

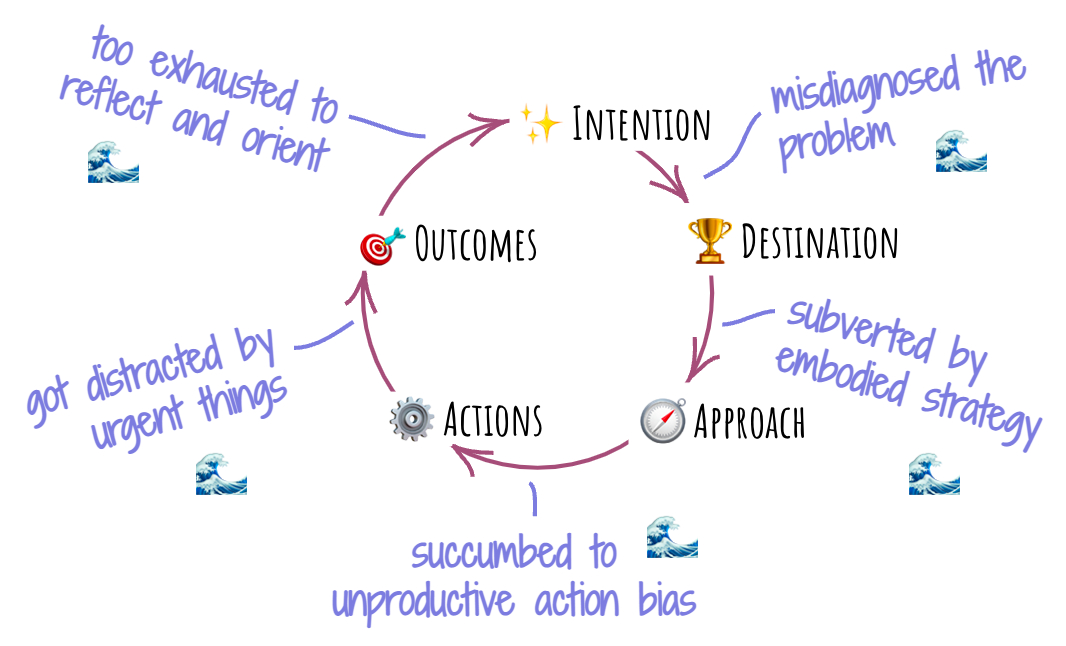

A well-known thinker in this area, Richard Rumelt, has done a lot of heavy lifting to unpack what good strategy entails. Building on his work, I’ll connect intentions and outcomes into a five-step cycle:

- It all begins with intention. There’s something in our environment that we would like to change. Formulated in terms of motion, this intention emerges as a question of “Where do we intend to go?”

- To answer this question, we engage in the diagnosis of the problem, which produces a destination: where we decide to go. The next question that we ask ourselves is, “How will we get there?”

- Devising a guiding policy answers this question, allowing us to arrive at the approach. Then, we move onto the next question: “How will we do it?”

- At this step, we come up with a coherent set of actions. Finally, something we can do! As we observe ourselves taking these actions, we ask ourselves: “What are the outcomes?”

- It is at this step where we usually encounter our first signals of whether we’re being strategic or not. Do the outcomes match the intention? The “What did we miss?” question is key, allowing us to compare what we see with where we started from—and repeat the cycle.

At every step in the cycle, there’s an opportunity for error that puts our intentions and outcomes at odds with each other. We’re constantly tempted to confuse our understanding of the situation with reality (“it is what we see”), and more often than not, we forget that our diagnosis is more of a hypothesis.

We’re swayed by our organizational habits, norms, practices, and culture (also known as embodied strategy) to choose approaches that are familiar rather than the ones that are called for by our diagnosis, veering us off course.

Urged to act, we end up making up our set of actions on the fly rather than considering them deliberately.

We’re distracted by the multitude of other things in front of us, failing to execute on what we’ve decided to do.

We forget to look back at our original intentions and check if the outcomes are incongruent, too exhausted to reflect on the evidence provided by these outcomes and improve our understanding of the environment.

All of these forces are, in the words of writer David Foster Wallace, “water.” We are in them, surrounded by them. We are them.

Being strategic means finding a way to become aware of these forces for more than fleeting moments—and then finding energy to countervail them. It means facing the headwind of what feels like “the most logical next step.” Because of this headwind, strategic moves are usually the ones that aren’t easy. Confusingly, hard choices aren’t always strategic. The difficulty of choices says nothing about their strategic soundness.

The only way to accomplish being strategic is through regular practice. Just like brushing teeth or regular exercise, it’s something we have to do in addition to all other things on our plate.

How do you know if you’re being strategic? Ask yourself the following questions:

- Do I have a general awareness of the cycle and the headwinds outlined above (or in any strategic framework)?

- Do I purposefully navigate this cycle as I conduct business?

- Beyond conducting everyday business, do I have a regular practice that helps me improve my capacity to be strategic?

Add one point for each “yes'' answer. Scored three points? Congratulations! Otherwise, we have work to do.

What is strategy work?

What does it mean to do strategy work? For the purpose of this narrative, I will use the term “strategist” for someone who does strategy work. Depending on the environment, it could be a designated role or just part of the job: of a leader or manager, or of an individual contributor.

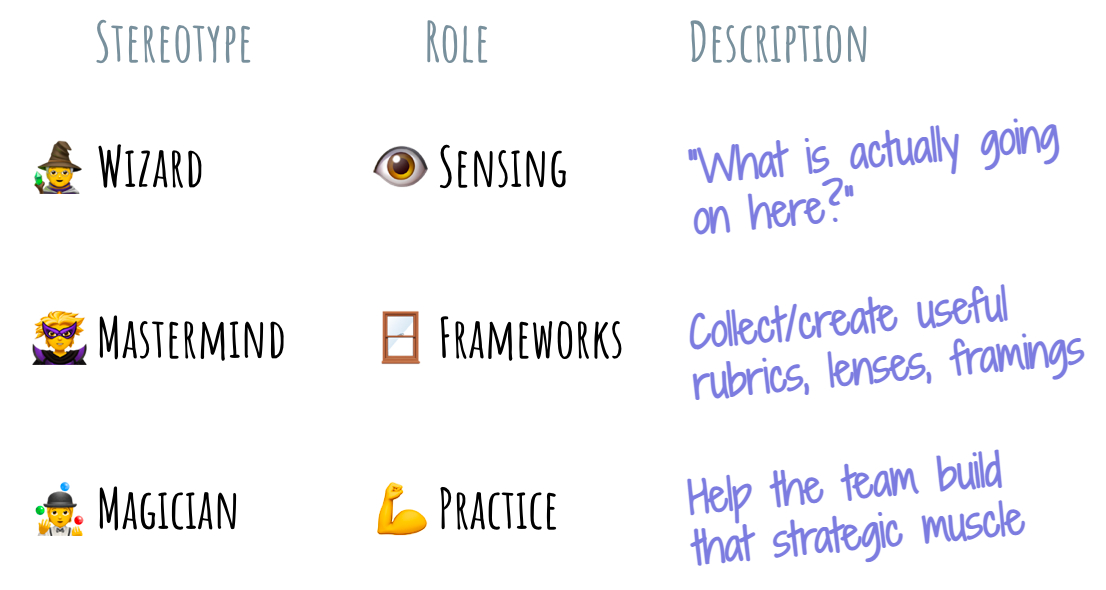

A few stereotypes arise:

One interpretation is a visage of a wizard: me sitting in an ivory tower, all-seeing, devising the next big artifact that will forever alter the landscape of the industry. This picture implies a power that no individual possesses, at least in practice.

Another interpretation is that of a magician, whereby I travel from team to team, setting them on the right path as a sort of strategy debugger. This depiction is popular in the tech industry, though I have doubts about the long-term durability of these engagements. A strategic bandaid looks suspiciously like an oxymoron.

Yet one more metaphor is a mastermind who is weaving the web of influence across the organization, quietly pulling strings to ensure that all the necessary bits are flowing to their proper destinations.

All of these are a bit cartoonish—yet all contain a grain of truth. Strategic work means having a perch to observe what’s happening across a broad swath of the organization and industry and providing a stream of insights. It also means engaging with various teams and helping them wrangle with their strategy challenges. And often, strategic work is about creating conditions for the right thing to happen as opposed to direct action, so behind-the-scenes influence is involved.

At its core, doing strategy works means helping an organization to be strategic. How do you even do that?

A clarifying perspective is that strategy is a team sport. One of the most common mistakes a strategist can make is to presume that they get to “make strategy.” They may produce a sleek artifact (it usually looks like a slide deck or a doc) that looks like strategy. They may even get the leaders to enthusiastically co-sign it.

However, unless this artifact describes what the organization already does, it isn't the team’s strategy. As a team, we make decisions that influence our team’s future. Every decision we make adds up to the sum vector of where we end up going. We all do strategy work. The strategy we end up with is what emerges from our collective efforts.

The mission of a strategist is not to set or devise strategy. It is to understand how an organization’s strategy emerges and why, then constantly scrutinize and interrogate the process, identifying inconsistencies and nudging the organization to address them. In this way, strategy work is a socratic process: gradually improving the thinking hygiene of the organization.

Now that we’ve diagnosed the problem and chosen the approach to strategy work, what is the set of coherent actions that a strategist undertakes to fulfill their mission? I’ll convert our earlier tropes into healthier roles.

The wizard evolves into the role of sensing. In a volatile, uncertain, complex, ambiguous (VUCA) world, staying deeply engaged with the environment is key. If we are to diagnose problems and understand the outcomes of our actions, we need to have clarity on what is going on. To be sensing means to stay aware of the variety of signals, curating them into a set of legible forces, patterns, and trends. Sensing needs to be both externally and internally facing—understanding what happens outside of the organization as well as inside. This is where that wizard’s perch comes so handy. To remain unbiased, observing and sense-making needs a detachment from the daily slog.

The mastermind turns toward frameworks. The objective of this role is to ensure that there are rubrics, lenses, and framings in place that help establish and grow the team’s shared mental model space—which helps build shared vocabulary that acts as scaffolding for effective strategic work. When one of the participants brings up the innovator’s dilemma or an invisible asymptote, and nobody else knows what that is, it’s a potential loss of insight: the lens drops on the floor. It wasn’t part of the shared mental model space. Who has the time to explain and deeply understand the concept? Conversely, in a large shared mental model space, people can talk almost in shorthand and still achieve high strategic rigor. Mental model hygiene is critical. Broken lenses (like “We should just work harder!” or “I would simply…”) can cripple or doom the team.

Finally, the healthy version of the magician trope is practice: the responsibility to keep the collective strategy muscle engaged. Instead of running from fire to fire, I want to proactively establish robust strategic thinking practice within my organizations. Such practice can take many forms, like systems thinking (understanding our context in terms of forces that are part of the larger system) and/or scenario planning (imagining futures by playing the forces forward).

Whatever it is, it must be something that spurs team leaders to shift from the minutiae of execution to think longer and broader.

With the practice in place, engaging with teams across the organization becomes a coaching function, rather than a reactive band-aid.

Juggling the roles

A strategist plays three roles at once: sensing, frameworks, and practicing. This is not an easy task.

Framework and sensing roles are nearly diametrically opposite in nature. Sensing implies wholly engaging with the full complexity of the environment, letting it wash over, spotting interesting trends, gardening collections of known forces and their traits. When I’m in a sensing role, I might spot something novel and groundbreaking, something that requires a dramatic rethink—and that’s where it runs straight into the framework role’s wall.

Because the framework role is charged with creating conditions for a shared mental model space across the leadership team, it is naturally conservative. When I’m wearing this hat, I want to ensure that there is a stable foundation of framings and lenses, neatly polished, accessible to all, easy to grasp, like tools in a toolbox. The sensing role keeps messing with this toolbox, questioning whether the screwdriver is actually a butterfly … and what if this wasn’t a toolbox, but rather … oh, I don’t know, a sunset?

Keeping both roles in one head is maddening and requires practice. Learning to separate framework and sensing roles was an important lesson in time management for me.

In addition to the need for a regular strategy practice within the team, the practice role is easily the biggest temporal vampire and randomizer of the bunch. The demand to jump in and help out with some strategic thinking ebbs and flows, and it’s difficult to know when the next interesting thing (that necessitates the jumping in!) will happen. Just when I have my framework and sensing hats sorted out, the practice hat barges in and announces that my help is needed.

Seeing water

Whether you’ve just decided to be strategic or are already doing strategic work, I salute you. Doing strategy work can be overwhelming and feel like going against the grain. It takes conscious effort to see “water.” I hope that the framings provided herein will serve you as a compass of sorts.

Dimitri Glazkov is a software engineer diving headfirst into the complex world of strategy. He works at Google and writes on his website.

Find Out What

Comes Next in Tech.

Start your free trial.

New ideas to help you build the future—in your inbox, every day. Trusted by over 75,000 readers.

SubscribeAlready have an account? Sign in

What's included?

-

Unlimited access to our daily essays by Dan Shipper, Evan Armstrong, and a roster of the best tech writers on the internet

-

Full access to an archive of hundreds of in-depth articles

-

-

Priority access and subscriber-only discounts to courses, events, and more

-

Ad-free experience

-

Access to our Discord community

Comments

Don't have an account? Sign up!

What an amazing read! Highly recommended!

Great article, especially these two passages...

"A strategic bandaid looks suspiciously like an oxymoron."

"One of the most common mistakes a strategist can make is to presume that they get to “make strategy.” They may produce a sleek artifact (it usually looks like a slide deck or a doc) that looks like strategy."

I did my best in attempting to define strategy here: https://wiljr.org/2022/04/25/what-is-strategy/

Great article! Well observed and clearly properly experienced in the real world!

Great article. I'm going to use this to frame a conversation in the coming week!

Wonderful article - the helicopter view is perfect, the zoom in is great contextualization, the metaphors are memorable and the visuals really help to capture the essential with a minimum of words. Simple, effective, memorable, actionable, what's not to like?!