Sponsored By: Hubspot

This essay is brought to you by Hubspot. Revolutionize your workflow with 10 glorious Google Sheets templates, tailor-made for entrepreneurs and versatile marketers. From organizing your blog's editorial calendar to mastering paid media strategies and optimizing on-page SEO, these ready-to-use spreadsheets are here to make a difference. Be the change you wish to see in your spreadsheet.

I have a confession to make: I’m a biography bro. Folks like me read books galore on the famous and powerful, trying to divine the secret to these fabled individuals' success. On my shelf sit volumes on everyone from Mozart to Martin Luther King to Robert Moses. I have written book reviews in which titans of industry espouse their philosophies. After all, it is fun to learn how others came to make more money than me.

However, I worry that people have gotten a smidge ahead of themselves. In a recent conversation, a founder of a B2B SaaS company said to me in earnest that “reading about how Napoleon conquered Europe helped him run his company.” He’s not alone: there are podcasts and workshops, study groups and Substacks, all of them devoted to the discipline of the powerful. It is a harmless hobby, but it is a funny one.

When Charlie Munger, the spiritual progenitor of the biography bro movement, died last week at 99, X was filled with hagiographies lionizing his legacy. The last week has bordered on—if not outright descended into—a period of spiritual mourning for Mungerites.

His philosophy is appealing, and his riches are undeniable. Munger, who had an estimated net worth of $2.3 billion, was the intellectual sparring partner of Warren Buffett, estimated net worth of $120 billion—and Munger, somehow, was noble enough not to murder Buffett over this difference in assets. Together they built Berkshire Hathaway, which has a market cap of roughly $775 billion. Not too shabby.

The key to his success? Mental models that are built by reading widely. To espouse his philosophy of success, 18 years ago he published Poor Charlie’s Almanac, a book of his teachings, that has been re-issued by Stripe Press. The whole thing is an ode to be being multi-disciplinary and widely read:

“You can’t really know anything if you just remember isolated facts and try and bang ’em back. If the facts don’t hang together on a latticework of theory, you don’t have them in a usable form. You’ve got to have models in your head. And you’ve got to array your experience—both vicarious and direct—on this latticework of models.”

Munger drew from the world’s well of knowledge to construct his models. In the reading list that accompanied the new edition, he included four biographies, and recent visitors to his home described shelves stuffed with profiles of the powerful. He, of course, read beyond this, with interests in psychology, mathematics, and biology.

Discover the power of efficiency with our Google Sheets templates, designed for the modern business landscape. Whether you're planning your next big marketing campaign or streamlining your content creation process, our templates have you covered. Experience the ease of an editorial calendar, delve into detailed paid media planning, and elevate your SEO efforts, all within a few clicks. These templates aren't just tools; they're catalysts for success.

And Munger’s own book is a repository of wisdom that argues for a distinct, pragmatic worldview. Many of my friends talk, at length, about how his writing has changed their lives.

I’ve read his book, done like Munger has done. The trademark wit and gumption he brought to his writing, with memorable lines like “being a one-legged man in an ass-kicking contest,” will be long lasting.

But I have a problem. I have absolutely no idea how to do what Munger says.

Munger’s method to getting rich

Munger’s perspective can be boiled down into five steps:

- To be a successful professional, you must be a multidisciplinary consumer of information.

- So, read a lot of books about smart dude stuff.

- Using all that reading, build many mental models.

- Use mental models to evaluate opportunities, only saying yes when it’s clear that an opportunity can be profitable for multiple decades.

- Be patient and repeat this process until you die.

This is sort of a finance horoscope. It is both specific enough to feel like it's meant for you and general enough to make everyone feel like it was written for them. The philosophy has the strongest appeal for widely read generalists. Read enough books, make enough mental models, and you will get rich.

I will admit to being slightly snookered by this process. I love to read. I also love the idea of betting on quality companies and then watching their value accrue for a decade.

Unfortunately, the primary issue is the mental models themselves. In the book, Munger argues that “80 or 90 important models will carry about 90 percent of the freight in making you a worldly-wise person. And, of those, only a mere handful really carry very heavy weight.”

Let that simmer for a second. Munger is suggesting that you should run every major decision—Munger’s were investment opportunities, yours might be career or partner decisions—through your really important models. Then, once they pass those models, run your decisions through the remaining 85 or so models. That is… not even slightly reasonable. Many choices we have to make are severely time-constrained, based on murky data at best. Most folks simply don’t have the bandwidth to analyze each major choice through the lens of all these models.

Even weirder, Munger would likely tell you that these mental models are not explicitly financial. They are not discounted cash flows or return on invested capital analysis. They are concepts drawn from biology or some other discipline far-flung from finance.

But I know for a fact that Buffett and Munger thought about financial metrics all the time. Buffett has even said that Munger’s biggest initial contribution was entirely around price:

“He actually hit me over the head with a two-by-four from the idea of buying very so-so companies at very cheap prices, knowing that that was some small profit and looking for really wonderful businesses that we could buy at fair prices.”

And in a Q&A in Poor Charlie’s Almanack, Munger says that financial “yardsticks” do play a role in decision-making:

Q: How do you and Warren evaluate an acquisition candidate?

A: We’re light on financial yardsticks. We apply lots of subjective criteria: Can we trust management? Can it harm our reputation? What can go wrong? Do we understand the business? Does it require capital infusions to keep it going? What is the expected cash flow? We don’t expect linear growth; cyclicality is fine with us as long as the price is appropriate.

Is a yardstick a model? Is it not? What is the difference? Munger never offers up any answers. Shoot, he has never even explicitly described most of his 90 models. In the book itself, I think he offers up about 30 mental models, but it is possible that I miscounted. Munger rarely calls out the boundaries of each idea, and they tend to marginally overlap.

I recognize that I am being nit-picky. However, I genuinely would like to emulate Munger’s success and life, so it’s important to take these details seriously.

I am not alone in this frustration. In a 1996 Q&A at Stanford Law School that is in the Almanack, a student pushed for a definitive list of sources and models. Munger shot back:

“There are a relatively small number of disciplines and a relatively small number of truly big ideas. And it’s a lot of fun to figure it out. Plus, if you figure it out and do the outlining yourself, the ideas will stick better than if you memorize ‘em using somebody else’s cram list.”

Let’s take him at his word—that we must discover the models for ourselves by reading books. The natural question is, “What books should we be reading?” In the accompanied reading list, Munger recommends 23 books. All are non-fiction, and all are written by male authors (one has a female co-author).

I don’t bring up this criticism to score cheap political points. Instead, I do so to highlight a problem with Munger’s philosophy. Our time on earth is precious and limited. Knowing where to deploy our resources is crucially important, and knowing what books to read is a critical challenge. You have to be smart enough to pick the right books and even smarter to pull out the correct insights.

Here, I have another problem: I am distinctly stupider than Charlie Munger.

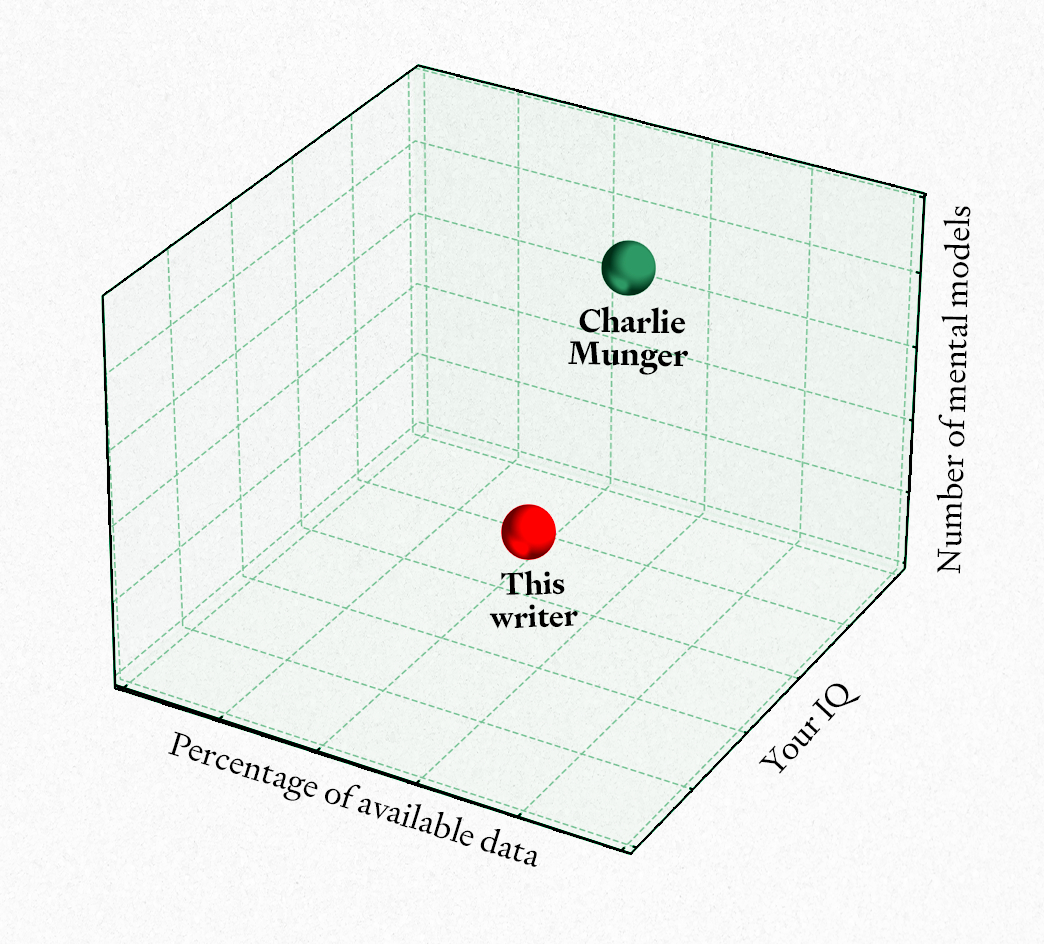

Visualizing Munger

Imagine a 3D model where the axes are:

- The number of quality mental models

- The percentage of total available data you can process on an issue

- Your IQ

There will be some minimum combination of all three that is required to select the right answer. Let’s say you have the 90 mental models Charlie suggests, 100% of all information on a topic, and an IQ of 1 million. You are guaranteed to make the right choice: you have the right frames by which to interpret the data necessary for analysis, as well as the IQ to understand what is happening.

It gets interesting when you try to find the ideal balance among these variables. If you have the right models and a high enough IQ, you can skip knowing everything there is to know about a topic.

The best investors I know are not the ones solely with the highest intellectual horsepower. They are the ones who can think the least, not the most. When an investment opportunity presents itself, they know what mental models to use and don’t worry about anything else.

What makes Munger’s advice in the Almanack challenging is that he is simply smarter than you or me. The models that he needs—the data he needs—are less obvious because his intelligence is so off the charts.

You can make yourself smarter through careful study, but there is only so much you can do. Most other investors have tried to compensate by building superior data pipelines or having differentiated mental models. The latter is the most enticing, as it only requires studying the right books, which feels accessible to most people.

Still, you have the problem of knowing which books to read. Even if you could come up with a master reading list, you might sit in a comfy chair for the rest of your life, desperately trying to come up with an investment edge.

Or you could use a technology that has comprehended nearly every book ever written. I’m talking, of course, about AI.

Oh, no, here I go talking about AI again

Theoretically, an LLM trained on all the science and non-fiction writing of the world would contain every mental model ever created. If you go back to the three axes of the graph, an LLM could outperform a human on every one.

- The number of quality mental models: Depending on the data that a model is trained on and how it is fine-tuned, an LLM could have a list of hundreds of mental models through which it runs every investment decision.

- The percentage of total available data you can process on an issue: LLMs aren't great at tracking and receiving data from lots of sources, so this is the biggest blocker. You can use GPT4 to do some basic analysis, but it isn't superior at picking out financial data from spreadsheets (yet). In a few years and/or with a few hundred million dollars, I think you could solve this.

- Your IQ: On the SAT, GPT4 tests at about the 90th percentile for humans. I imagine if the growth curve continues, we’ll have something at the 99th percentile within five to 10 years, if not far past that at superhuman intelligence levels.

My colleague Dan has written about how one might emulate Munger using ChatGPT. However, the process is still fairly clunky and requires lots of workarounds and hand-holding.

The AI might soon be able to cover up any deficiencies you have in thinking the Munger way—but for now, you are stuck doing the best you can. And I remain unconvinced that super-intelligent AI investing companies won’t be table stakes for median alpha generation. Even if you can have Munger3000 as your investing advisor, so can anyone else.

To all of my fellow biography bros: we forget 99% of what we read. Very few insights will stick with us. Instead, we read to cultivate a state of being that opens us up to knowledge. Reading Munger’s book hasn’t imparted much new wisdom. Some of his more atypical life advice, such as avoiding addicting “chemicals,” has been preached by my Mormon ancestors since long before Munger was born. Still, the book is a reminder to invest wisely.

Perhaps that will be the ultimate legacy of Poor Charlie's Almanack. Not a defined set of models, or a prescribed pattern of living, but instead a state of being—curious, practical, and wise.

Find Out What

Comes Next in Tech.

Start your free trial.

New ideas to help you build the future—in your inbox, every day. Trusted by over 75,000 readers.

SubscribeAlready have an account? Sign in

What's included?

-

Unlimited access to our daily essays by Dan Shipper, Evan Armstrong, and a roster of the best tech writers on the internet

-

Full access to an archive of hundreds of in-depth articles

-

-

Priority access and subscriber-only discounts to courses, events, and more

-

Ad-free experience

-

Access to our Discord community

Thanks to our Sponsor: Hubspot

Thanks again to our sponsor Hubspot. Upgrade your potential with 10 exceptional templates, each crafted to enhance your business acumen. Say goodbye to the hassle of starting from scratch and hello to a world of streamlined processes and improved productivity. It's time to transform how you work, one spreadsheet at a time.

Comments

Don't have an account? Sign up!

Good stuff. This whole area of chasing wealth/success by picking heroes has always felt limited to me. Further to what you outlined I also think trying to emulate successful people by doing what they *say* they did likely has significant limits on its potential for actual success in that goal. If you could study them from the outside and avoid their own biases and blinders about their good and bad qualities, it might tell you something more. But in the end you're right that one's ability to actually emulate is limited, even with perfect information on how someone achieved their success.

Regarding AI and the Munger3000 that might relatively soon be widely available, I'm particularly curious to know how you think this might affect *how the market works*? How things are valued, etc. In theory it should get us closer to the idealized market of "perfectly informed economic actors" and thus might make the market run better/smoother, right? Maybe even act as a stabilizing counter-force to the high speed trading revolution that occurred some years ago... But what's your take?

@Oshyan couple things on the market side. Alpha isn't just found in pricing, but in access and speed. Many hedge funds already trade using machine learning, so layering in LLM trades doesn't feel unreasonable. It'll likely end up exaggerating the winner take most dynamics for most types of assets.

@ItsUrBoyEvan Damn, I really hoped that *wouldn't* be the case. 😄 My angle was that giving access to AI-driven trading to basically everyone could be a leveler. It would almost certainly work differently than current ML and high speed trading because they're mostly unavailable to the general public, at least at the highest levels.

Of course you could argue that the bigger players will have better AI, and that's probably true. But I'm pretty confident that the distance between the average person and a perfect trader is much greater than the same distance for a current top-level market player. The dominant players go from 95% perfect to 97% or even 99%, great, but the vast, uninformed masses *could* go from say 30% to 70% (totally made-up numbers, but most people have no idea how to pick stocks well, time a trade well, etc.).

Of course many people are invested in funds anyway, so they're already effectively participating as high level players, collectively (in that fund). So I guess my theory depends on how many amateur traders in the open market there are (people picking stocks, doing day trades, etc., i.e. not primarily in managed asset pools) and what volume of the market they influence.

It was definitely a hot take, not fully thought out. But it still feels like there is a nugget of potential interest there. 🤔