In a company, being right isn't enough—you need to know how to sell your ideas, especially to those at the top. Evan Armstrong learned this lesson the hard way. This piece from last fall chronicles his evolution from frustrated analyst to successful persuader, using an example from Every. Evan breaks down his approach into three strategies: weaving compelling narratives, understanding the psychology of decision-makers, and preparing for objections with "gotcha slides." Let us know what has worked for you in the comments.—Kate Lee

Was this newsletter forwarded to you? Sign up to get it in your inbox.

Everyone has a boss, and God, in his infinite appetite for cruelty, will almost certainly ensure that said individual is a dumbass. Maybe you spit on an Indian burial site and got cursed. Maybe low IQ is a prerequisite for VP titles or board seats. Who knows. Regardless, you are going to have to learn to deal with people more powerful than you. So learning how to navigate an organization is one of the most important skills for a career. Yes, it is trite and bleak and horrible, but I would prefer a colleague who can get the VP to agree with what our team wants over any other capability.

The need for this skill is especially acute for those of us who do analysis for a living. Whether you are tasked to build a financial model, a dashboard on user data, or a flowchart of workflows, if you are semi-regularly asked, “Can you figure that out?” this guide is for you.

These are hard-won lessons. Frankly, for most of my career I was atrocious at this. My analysis has always been good, but I sucked at translating the spreadsheets into company change. I (foolishly) thought that “data would prevail” or “management will do what the math says we should.”

But what data is, or what “right” even means, can be strongly skewed by incentives or bias. Even though most firms should base their decisions on analytical rigor and risk-adjusted investment, they end up doing so based on hubris.

So, after nearly a decade of doing this wrong, please learn from my mistakes. These skills should be used for good (improving the company’s chance of success) but are also applicable in a more Machievellian sense, if that’s your sort of thing. To make this feel more real, I’m going to walk you through a work of analysis I did here at Every. Using it as a framing device, I’ll share three ways to use narratives, psychology, and gotcha slides to win at work.

Toro, toro, toro

I think of founders and executives as bulls in the budget shop. They’re strong and powerful and ill-tempered and a smidge destructive. The skills that let them ascend to the top of an organizational structure very rarely include analytical rigor. Great founders and CEOs typically shine in their ability to understand and communicate stories. Their job is to rally investors and team members—with the most universal way to do so in charisma and charm.

These are the people you need to convince, so instead of trying to teach them how math works, adjust your math to their story.

Whenever I’m presenting an analysis, I like to start with the story of how we got to the need for this analysis to be with and why this math matters—fairly normal advice. However, I’ll take it a step further.

Rather than rattle off the numbers along with my suggested fix, I’ll wave three red story flags in front of the executive’s eyes. Each discrete work of analysis has an accompanying story to be told. Your job is to get the bull to pick which flag to charge at. Since founders are the bulls in the arena, you either give them a target or they will just rage about willy-nilly. As you get better, you’ll be able to present all three stories, but they’ll charge the one you want every time.

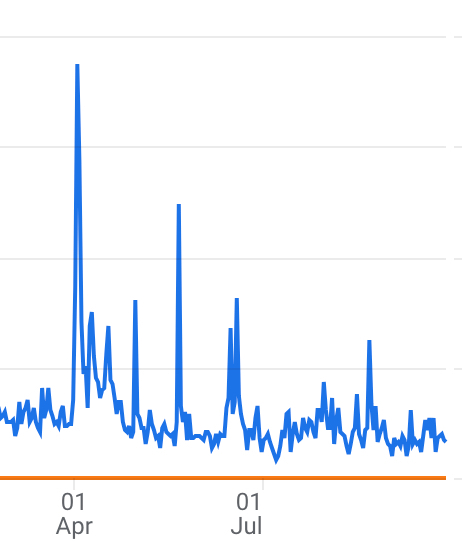

At Every, top of the funnel has always been our biggest concern. Our traffic mostly derived from people sharing our essays on social media—in particular, on Twitter. Unfortunately for us, Twitter was bought by Grime’s jilted ex-lover, who instituted algorithmic changes that have decimated one of our best sources of traffic. Since we need, like, customers, this is a business-is-on-fire situation.

I put a meeting on everyone’s calendar called “I got 99 growth problems and Twitter’s the biggest one.” When we met, I started off by showing the overall traffic decline to Every’s website. Then, I showed this chart of Twitter views volume.

Source: Google Analytics (a product so abysmal that I can’t get the damn charts to do what I want or look how I want or show what I want. I hate I hate I hate).I didn’t show this because Every CEO (and my boss) Dan doesn’t know that Twitter sucks now, but because I got him to focus by waving that red flag. He has a lot on his mind (note from Dan: "for example, my lead writer says unhinged things about me in this newsletter"), so getting him to dial in is important.

In my preparation for the meeting, I knew that I would need Dan to approve a few growth initiatives. I had done a bunch of math that showed which ones were most likely to work, but he needed to OK the new workflows. Thus, the red flags.

Instead of walking through all of the math that led me to select each of these options, I told the story of each initiative. One of those ideas was a VIP program I wanted to run. There were two ways I could tell that story.

The first way is boring:

“Dan, I manually went through 29,564 emails to select 112 VIPs. From there I categorized each of these VIPs by what they could offer us from a following, power, insights, or financial perspective. If we do X, Y, and Z, it is reasonable to forecast a 20% webviews improvement within two quarters.”

This is, again, boring as hell. Instead, I started with:

“Dan, remember how your piece with Andrew Wilkinson performed so well? It’s a great piece, but it resonated because people on Twitter love that Canadian dude. I think we can do it again. For example, here are three VIPs you know that we can feature. If it works, I have prepared a list of 112 VIPs that we can go after next.”

Same data, but wholly different vibe. The second option feels personal and real as compared to the first, which is cold and rote. The more you ground your analysis in the founder’s personal history and intuition, the easier it is to get what you want approved.

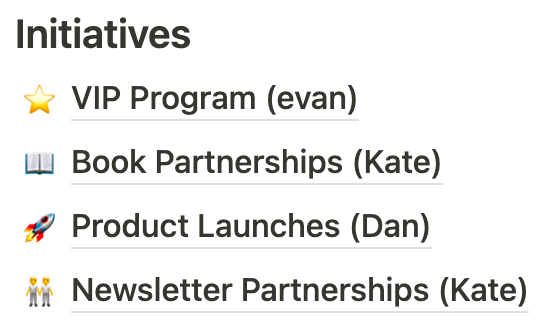

I repeated this approach four times with each growth lever my analysis said was important. Here is where we ended up:

A screenshot from our internal Notion.The reason to ground your analysis in narrative is because there are essentially infinite ways to pick apart a piece of it. If a founder is doubtful, they’ll give you the runaround and ask, “Are we measuring MAU correctly?” or “Can we go a layer deeper?” The fastest way around this is to tell the story of the initiative while weaving it into the grand narrative of the business.

So how do you pick which red flag to wave? How do you select the narrative that is most likely to get your resources approved?

Fondle the nethers

On the corner of Broadway in New York’s Financial District stands Wall Street’s bronze bull. Tourists love to come and worship this idol of capitalism. Anytime you go there, someone from Kansas City will be taking a selfie while rubbing the horns. Consequently, while most of the statue is a dull brownish color, the head is shiny, polished bronze. Well, actually, there’s another part of the statue that’s shiny. Tourists also enjoy caressing the balls.

Credit: Google Image. This unfortunate person is the result when you Google “Wall Street bull’s balls.”If founders are the bulls in the budget shop, narrative-driven analysis is the head scratch, and psychology is the ball squeeze. An entertaining story is not enough to get a manager to sign off on an investment; you need to tell the story based on their preferred rhythms and ways of working.

As dumb as it sounds, making sure your boss is in a good mood is more important than being right. This is where I failed for many years. In my love for “solving the puzzle,” I thought others would feel the same way.

Who do you think the most important person is in getting your analysis approved? You? The founder? The VPs in adjacent functions? Wrong. It is probably the executive assistant. If they don’t like you, they’ll schedule you at the worst possible time with no advice on how to get the executive's attention. A true story: my friend, who was a management consultant, got on the bad side of the EA. The EA scheduled his performance review immediately after the boss’s meeting with his divorce lawyer. (The review did not go well [and neither did the divorce]).

There are a few easy wins that have helped me in my career:

- Never schedule a meeting right after a meal (sleepy).

- Want to get something approved quickly without much oversight? Pick a meeting time when the founder knows they should be focused, but can’t bring themselves to care. Friday afternoon is ideal.

- Early morning or late night meetings are a great way to win favor. I had a manager who loved when I would send a bunch of emails over the weekend because it showed I was “grinding.” The reality is that on Friday, I would schedule them all to be sent over the coming days, but you get the idea. Early mornings or late nights will make a founder think, “They care as much as I do.”

What makes psychology challenging is that the founders know you are doing this. They know everyone on their team is trying to manipulate them! It becomes a game of psychological chicken: a wily executive knows their underlings are actively trying to manipulate them, the underlings know they know, the founder knows that they know they know, etc.

Dan values emotional honesty. (Our weekly standup kicks off with each of us describing our mood in colors, lol). I am most successful when I say, “Dan, you have a history of emotional avoidance of this type of problem. I need you to directly confront it.” This is very unique! If I had done that with some of the VCs I worked with, I would not be alive to type this essay today.

I scheduled the growth meeting to discuss the VIP program on a Tuesday afternoon because Dan doesn’t like morning meetings and gets sleepy from 1-2. I started it off with some jokes to beat back his worry. Making the meeting pleasurable for his unique psychology made it more likely he would approve what I wanted—which, thankfully, he did. The VIP program is now running.

Still, even if you have a good story and the right time for the meeting, you’ll need one more thing: the ability to say, “I told you so.”

Behind door number three

Even if you nail the story and the psychology, the meeting will almost assuredly go off the rails. Founders are bulls, after all! Ask any rodeo clown—you can only sorta control what a pissed-off Brahman will do. The test of a truly great analyst is if you can forecast how a founder will get distracted. Will there be a number they dislike? Is there some part of your proposal they will doubt?

Knowing these in advance, you can prepare “gotcha slides.” These are artifacts for when the founder pushes back. You can say, “Great question! I prepared a slide in case you had that concern.” Being able to answer the question matters, but more important is demonstrating that you were prepared. The goal isn’t to actually resolve the concern—it is to make the founder feel comfortable trusting you. Do this 3-6 times early at a company, and you’ll eventually get far more leeway because your bosses will trust that you’ve already done the “gotcha” work.

Thankfully at Every, I am far past the point of needing to prepare gotcha slides. However, especially early in my career, when executives assumed I was young and stupid, my appendix would often be longer than the presentation itself. Yes, this is excessive and neurotic. But if you want to get big responsibility fast, you have to earn it.

Getting executives to act requires art as much as science. Data has a role, but the path from analysis to alignment runs through compelling stories, keen emotional intelligence, and anticipating concerns. Master these, and your spreadsheets will shape strategy.

Evan Armstrong is the lead writer for Every, where he writes the Napkin Math column. You can follow him on X at @itsurboyevan and on LinkedIn, and Every on X at @every and on LinkedIn.

We also build AI tools for readers like you. Automate repeat writing with Spiral. Organize files automatically with Sparkle. Write something great with Lex.

Find Out What

Comes Next in Tech.

Start your free trial.

New ideas to help you build the future—in your inbox, every day. Trusted by over 75,000 readers.

SubscribeAlready have an account? Sign in

What's included?

-

Unlimited access to our daily essays by Dan Shipper, Evan Armstrong, and a roster of the best tech writers on the internet

-

Full access to an archive of hundreds of in-depth articles

-

-

Priority access and subscriber-only discounts to courses, events, and more

-

Ad-free experience

-

Access to our Discord community

Comments

Don't have an account? Sign up!

Absolute garbage. Where's your stats on this 'opinion'?!

(Had a large lunch, bad news from my accountant)

Otherwise brilliant, funny and a great read all the way down.

@hollywoodsign Hi Colm, this is Kate Lee, the EIC of Every. Thank you for this (hilarious) feedback. We'd like to feature it in our Sunday newsletter. Would you please respond (or email me directly at kate@every.to) with your industry/job function? Thank you!