Hey all - Adam here. Hope everyone is staying sane during the past couple days. This week I have a post by Conor Durkin about political betting markets. Hopefully you can learn something about why the election was predicted in certain ways — I know I did. Let me know what you think through the form at the bottom. Enjoy!

Welp, it’s a nail-biter. Yet again, despite the predictions of polls and pundits, there was no blue wave and no clear landslide victory last night, and there’s not likely to be a clear winner for days. Why are we so bad at predicting politics?

Pundits are motivated by ratings. Pollsters struggle to get enough voters to answer questions, they may be asking the wrong questions, and they might be lied to anyway. As Democratic strategist Chris Kofinis put it: “Polling is as much an art as a science; unfortunately some artists are really bad, and others ignore the science.”

This year, as the election drew near, Nate Silver’s political forecasting site 538—which uses polling and other data sources, like economic indicators, to make predictions—gave Vice President Biden roughly an 89% chance of winning. 538 has a pretty good track record, and though there are disagreements in methodology, another statistical model, from The Economist, put Biden at 91%. But polling models, including 538’s, were wrong in 2016, and looking at the map now, faith in the power of their predictions is falling fast, even if Biden does ultimately prevail, as he now looks likely to.

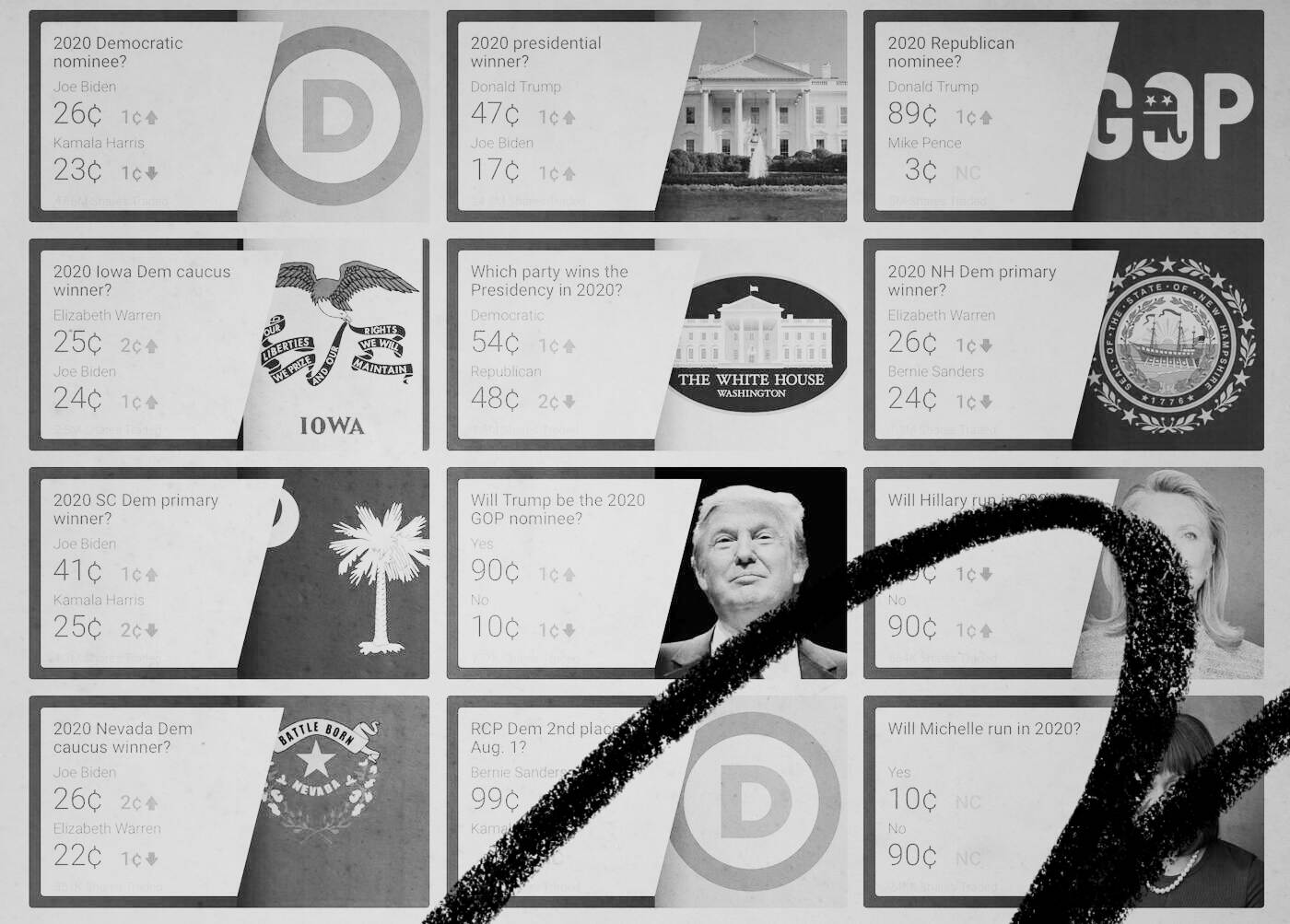

Beyond the models, last night also showed a lot of attention going towards a newer data source for predicting election results — betting markets. Just like in horse racing, a candidate’s odds in a betting market could tell us something about their probability of winning. One online political betting service, PredictIt, put President Trump’s chance of winning as high as 40% (to 538’s 10%) as of the day of the election. Betfair, out of the U.K., puts Trump at 33%. As of this morning, political betting markets give Trump a 25-30% chance.

No state in the country has legalized political betting, but as they become more well known, it’s worth taking a closer look at whether the betting markets overseas might be better forecasters than our polls and pundits. Is political betting the future of predicting politics?

What is a prediction market?

There are two basic markets in which you might bet on politics. The first is at a sportsbook, many of which offer political wagers alongside their traditional sports and horse racing wagers (some have tried to legalize a political sportsbook in the U.S). The second is in a prediction market.

Like a sportsbook, prediction markets are places where individuals can place bets (or ‘trade contracts,’ depending on how heavy you like your euphemism). Unlike a sportsbook, however, in prediction markets prices are entirely determined by the participants trading in the market—an order book matches buyers and sellers so that the prices a market trades at are whatever clear the market. This is similar to how most other financial markets work, except the securities you’re trading are bets on the likelihood that a real-world event occurs.

Typically, a prediction market contract pays out $1 if an event occurs or $0 if it does not; the probability of the event can then be understood to be whatever price the contract is trading at[1]. Prediction markets allow individuals to profit by making more accurate predictions than the 'wisdom of the crowd' would as a whole—if individuals think an event is more likely to occur than its trading price implies, they can buy shares at that price, and make a profit if they’re right. Conversely, prediction markets can also add credibility to individuals’ predictions, or hold them accountable for outlandish predictions. Talk is cheap. But if they think the market is wrong, are they willing to put skin in the game?

As with sportsbooks, legality of prediction markets varies in the U.S.. The best known legal political prediction market is PredictIt, an online exchange run by Victoria University in New Zealand (which received CFTC approval to operate ‘for research purposes’ so long as they enforced string limits on trading). In the U.K., Betfair provides another useful example (unlike most sportsbooks, Betfair's prices are set by matching buyers and sellers of wagers as a market would, rather than having a bookmaker take all wagers). These markets allow people to wager on a variety of contracts related to politics ("2020 presidential election winner," "will California Prop 22 be approved in 2020," "which party will win Pennsylvania in 2020," "total turnout in the presidential election," to name a few).

What makes a good prediction market?

The next question, then, is what makes a prediction market good? Tautologically, it’s one that makes good predictions. In the language of classic finance, a good market is efficient. That means that prices reflect all available information, so it’s impossible for someone to achieve ‘above market returns’ and beat the market—any outperformance is just luck. If the market isn't efficient, the prices aren't right. In the context of a prediction market, wrong prices would mean inaccurate probabilities, which means it’s useless as a predictor.

So, what characterizes an efficient market? Three things come to mind:

- Liquidity. It should be easy to trade at current prices. If it’s difficult to trade (perhaps there are few buyers at current prices, or the bid-ask spread is quite wide) then fewer traders will want to participate. More participants mean more trades and more interest in the market, which result in better information dissemination through the market.

- Depth. Again, it’s better to have more participants in a market, not just a few people driving prices. In those cases, the opinions of one or two major players could have an outsized impact on where prices end up, which isn’t always reflective of where the prices ‘should’ be.

- As a result of liquidity and depth, traders should then be able to get rid of ‘wrong’ prices. This is a bit similar to the role arbitrage trading plays in the stock market (when there are discrepancies in the market reflecting bad information, somebody has to correct the market), but it’s also about the market being able to quickly absorb new information (polls, or economic data, or other relevant news that would impact an election) when it becomes available. If traders are unable to do that (because of transaction fees, or trading limits, or something else), then markets will be less accurate.

With those three things, you can get a pretty good market view of an event's likelihood! Without them, things can get a bit screwy.

To demonstrate, let’s imagine two markets—one in which all trades are free, and one in which trades cost 10 cents per $1 traded. Now pretend that we know Joe Biden’s odds of winning Arizona are definitively 50%. In the first market, shares of “Joe Biden to win Arizona” will have a very defined price—it should be exactly $0.50. Any more or any less, and a trader should buy or sell shares until the price reaches the real odds. In the second market, in contrast, the shares will have a much wider range, anywhere from 40 to 60 cents. Inside of that range, the fees traders have to pay make the market too inefficient to reach the “right” price, since the fees paid outweigh the degree to which the price is wrong. If someone wanted to use these markets to understand the probability of a candidate winning, the first market would have a very precise estimate, while someone looking at the second market would have a really wide and undefined probability range to consider.

What could cause a market to be wrong?

Again, the tautological answer is that a market can be wrong if it’s not a very good market. PredictIt, for example, has a maximum investment limit of $850 in any given market, which isn't great for liquidity and isn't very much if you're trying to encourage sophisticated traders to get involved: it simply isn’t profitable to build out sophisticated estimates of the market when your upside is that low[2]. Their trading commission structure is also somewhat onerous, compared to the bookmaker’s hold in most sports betting or a broker’s trading fee in most financial markets. PredictIt takes 10% of the returns on any profitably trade, and they have a 5% fee on any withdrawals from the platform. As with any other financial transaction fees, these reduce traders’ ability to correct prices they see as wrong, and the larger the fees, the less efficient the market may be[3].

On the other hand, the prices in prediction markets seem reasonably consistent across different platforms, with the UK's Betfair or the decentralized Augur platform showing similar odds. These markets are more liquid and efficient: Augur has a few hundred thousand dollars in wagers on the election thus far, and U.K. gambling companies have stated they expect volumes to break records set in 2016. The only other explanation is that if the market consensus is wrong, it isn’t a result of issues related to liquidity or the efficiency of the market, but simply to market participants just betting on the wrong horse. What could explain that?

For one, political betting is still a fairly immature market, and elections aren't all that common (particularly compared to sports, where hundreds or thousands of games might be played a year). As such, it's unlikely there are too many 'sharps' or sophisticated gamblers who make a living wagering on political outcomes. In sports betting, these sophisticated market participants are very important. They're often the ones who drive price changes from a bookmaker's posted lines (think of this the same way an arbitraging hedge fund moves prices more than a massive index fund will—one is a price taker, one is a price maker). In a market of only unsophisticated bettors, pricing is more likely to be wrong. In the case of the higher probability the political betting services are giving to Trump this year, it seems particularly possible that bettors are operating on a recency bias, with gamblers giving too much weight to the 2016 outcome relative to what models think is appropriate.

The last potential explanation is a bit darker, but it's possible that the "model versus market" discrepancy isn't really a discrepancy at all—they're just predicting different things. The model aims to predict how people will vote in the election, the market aims to predict who will win the election. We've already seen quite a lot of drama regarding the electoral process. It could be the ~23 point discrepancy between models and the market is reflective of the market's view for potential election manipulation outside the typical process, either involving the courts or other means. I'm skeptical that's a good explanation, but it's hard to dismiss out of hand.

I'm optimistic about the future of prediction markets, but it's clear that currently they don’t meet the liquidity and depth requirements needed for us to rely on them fully as of yet - though looking at the news today, it’s possible prediction markets may have figured something out that the pollsters and pundits didn’t. Regardless, it’s clear to me that prediction markets are here to stay.

[1] E.g. the contract for a 50% probability event should trade at $0.50 or so.

[2] To put this in context, while limits at sportsbooks often vary, limits on NFL games (one of the most liquid sports gambling markets) are typically in the range of several thousand dollars per game.

[3] For example, if “Donald Trump to win the election” is trading at a price of $0.39, and a trader feels very certain that his odds should be 41% or so, he’s incentivized to buy shares, pushing the price up (in theory, he could keep buying until the price reaches $0.41). However, if his winnings from a correct bet are reduced by 10% while his losses from an incorrect bet aren’t reduced at all, the range for which it’s not profitable to move prices becomes much wider. At a price of $0.39 and a 10% fee on all profit, it’s not profitable to buy any shares at all unless you believe President Trump’s odds to win are at least 41.5%.

How did you feel about this post?

Enjoy this post? Subscribe to Napkin Math Premium

We’re striving to make Napkin Math Premium the best possible resource for finance and investing analysis.

When you become a member you’ll get additional in-depth articles only available to subscribers, including:

- How Datadog became the $25 billion leader in Observability

- Why The New York Times is going to continue to grow at breakneck speeds

- Why school bus operators are an overlooked investment opportunity, and a database of 60 companies to get you started

Napkin Math also comes as a bundle, so when you subscribe you also get access to all our other paid newsletters: Divinations, Superorganizers, Praxis, Means of Creation, Ask Jerry, The Long Conversation, Free Radicals, and Almanack.

Find Out What

Comes Next in Tech.

Start your free trial.

New ideas to help you build the future—in your inbox, every day. Trusted by over 75,000 readers.

SubscribeAlready have an account? Sign in

What's included?

-

Unlimited access to our daily essays by Dan Shipper, Evan Armstrong, and a roster of the best tech writers on the internet

-

Full access to an archive of hundreds of in-depth articles

-

-

Priority access and subscriber-only discounts to courses, events, and more

-

Ad-free experience

-

Access to our Discord community

Comments

Don't have an account? Sign up!