Over the last year I filmed a short documentary on the life and artistic career of my father Wayne Forte. He has been one of the strongest influences on me, not only as a father, but as a prolific lifelong artist.

I wanted a way to share his remarkable story with a wider public, to preserve a record of his memories for future generations, and to better understand the roots of my own ideas.

I used only the most basic equipment: a smartphone, a microphone, a tripod, a stabilizing gimbal, and video-editing software on my computer. I had no film crew, no expensive cameras, and did no post-production except what I could accomplish on my own.

I had never made a film before. I had no real experience with sound, cinematography, lighting, scripts, interviewing, editing, or any of the dozens of specialities that go into making films. I didn’t even have much of a plan when I started. I simply turned on my smartphone camera and started recording.

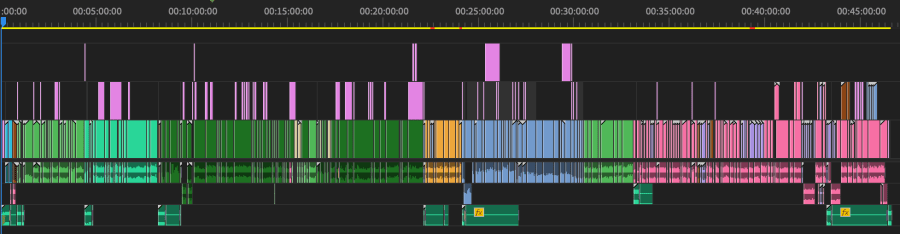

It took 16 months, more than 100 total hours of work, and 17 hours of footage from 4 countries, all condensed down to 46 minutes.

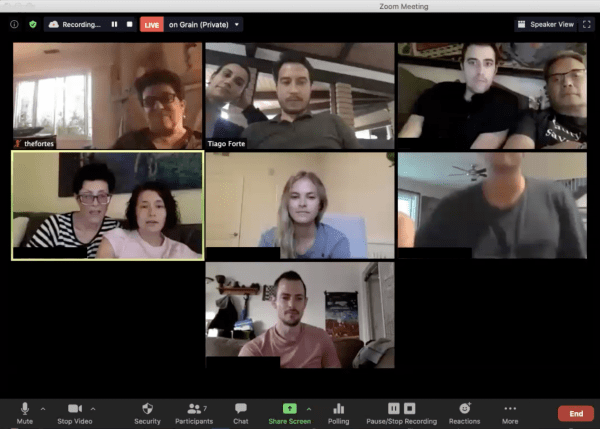

When I finished the final cut, I premiered the film on YouTube in a coordinated viewing with over a hundred family, friends, and random Internet strangers watching from their homes in the midst of a global pandemic. In the couple months since, the film has been viewed more than 6,000 times by people around the world.

Every part of this story would have been improbable or impossible just 10 years ago. It was enabled by a quiet revolution in our ability to tell long-form stories using video, disguised as a steady stream of hardware and software updates every year.

This is the story of how I did it, what I learned, and the profound implications for the modern creative process I discovered along the way.

The Project

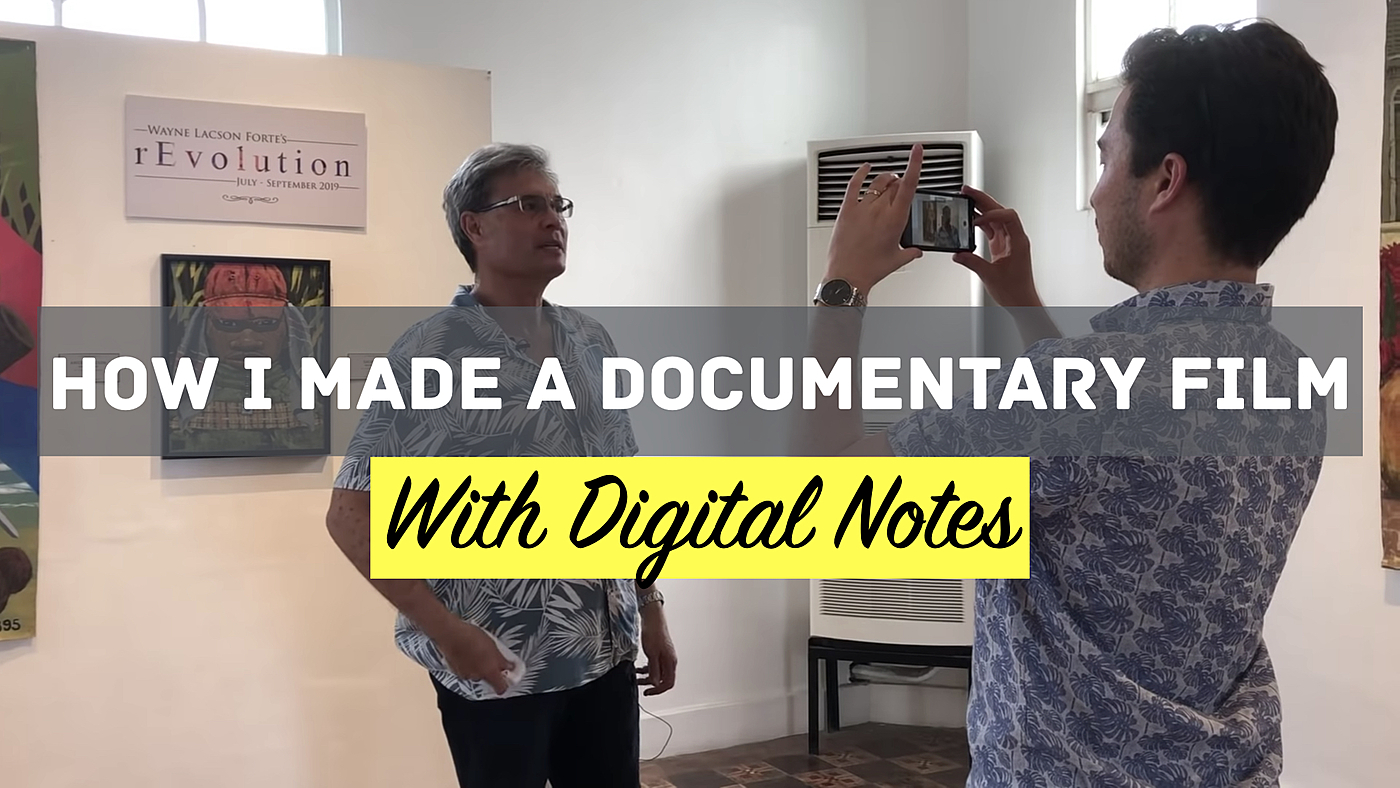

In March of 2019 I received news that an art gallery in Los Angeles would be hosting an exhibition of 30 years of my father’s Biblically themed artwork.

This was a huge milestone for him. And not just because it would be a prominent showcase in the heart of Hollywood. He had had a lot of success with his paintings of figures and still lifes, but the secular, mainstream art world had never embraced his religious art, which has long been his true passion.

Here was a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity to showcase decades of his most personally meaningful work in his hometown. I was living in Mexico City at the time, and decided to fly back to be there.

From there it quickly became a project.

If I was going to fly all the way back to the U.S., I thought, I might as well film the opening night. If I was going to film the opening night, I might as well do a few short interviews with the friends and collectors who would be there.

And if I was going to do all that, why not just film a few other interviews while I’m in town and tell the story of my dad’s career as an artist?

In my productivity courses I’m constantly advising people to “dial down the scope.” In other words, to reduce the size and complexity of their projects so they have a better chance of finishing them.

But once in a while, a project comes along that is so interesting, so unique, and so meaningful that it’s worth dialing up the scope. The main purpose of keeping most projects small is so that when a really special one comes along, you have the time and space to make it big.

I realized that by making this film, I could accomplish a few different goals at once.

It would be an opportunity to learn how to make higher quality, longer videos to promote my work. I’d long wanted to be more active on YouTube, but without a hands-on project, I never seemed to get around to it. I sensed the revolutionary implications of everyone walking around with a professional-quality camera at all times. I knew I needed to get my hands dirty to be a part of it.

I also had a more personal motivation. A few years earlier, my dad had had a cancer scare. Although he was now fully recovered, it had shocked me with the realization that he wouldn’t be around forever. As I looked forward to starting a family of my own, I wanted to document his life so my future kids would have the chance to know him like I did. And to better understand for myself how his attitudes toward art, creativity, productivity, spirituality, and life in general had so deeply influenced my own.

At first glance, this was an absolutely absurd project for a novice to take on.

I had made a few short videos on YouTube, but nothing anywhere close to this scale or complexity. I didn’t have any special equipment, had never used professional video editing software, and didn’t know the first thing about lighting or sound.

But I did have one trick up my sleeve: my system for digital note-taking, which I teach in my course Building a Second Brain. I knew that I could easily manage the information that I’d need to plan, organize, and execute the project using digital notes.

16 months later, on June 2, 2020, my dad’s 70th birthday, I screened the final cut for my family online. We watched it together at a coordinated time, and had a touching conversation afterward on Zoom about our shared memories.

It was truly one of the most special and meaningful moments with my family that I can remember.

A month later I screened the film again for my followers using YouTube’s Premiere feature. I shared the starting time and a link with the subscribers of my weekly email newsletter, and over 100 of them showed up to experience it together.

As promised, I’m finally ready to share what I learned.

From how I managed the whole project using digital notes, to what I learned about interviewing, to what I discovered about creating virtual community, to the future potential of amateur films. I’ll share screenshots of all 21 notes I created along the way, explain how I used them, and give you my best advice on how to make a film of your own.

The role of digital notes

This project simply would not have been possible without digital notes.

From the very beginning, I needed an easy, lightweight way to manage large amounts of information. For example, scenes to shoot, questions to ask in interviews, filming tips, editing guidelines, examples to borrow from, lessons from other films, checklists to follow, and many other logistical details.

There are a few things that make notes uniquely suited to amateur filmmaking:

- They are casual, fitting easily into the small moments of the day

- They are multimedia, allowing you to capture text but also screenshots, still frames, pictures of backgrounds or locations, etc. in one centralized place

- They are mobile-friendly, allowing for easy entry and retrieval when you’re out and about filming

There are specialized software programs available for managing full-scale film projects. But I wasn’t a professional filmmaker and couldn’t afford to dedicate myself full time to the project. I didn’t need a sophisticated tool nor did I want to learn a new interface.

What I needed was a quick and dirty way of making small bits of progress whenever I had the time, approximately 1-2 days per month. Notes perfectly fit the bill.

There were five overlapping stages I moved through in this project:

- Research

- Planning

- Filming

- Editing

- Screening

Let’s examine the notes I used for each one.

For Members Only

Because you’re a Praxis member you can download the full content of all 21 notes shown below in both Evernote and Notion format. You can borrow from what I learned, explore how I construct notes, and even use my notes as a template for your own video project.

STAGE 1: RESEARCH

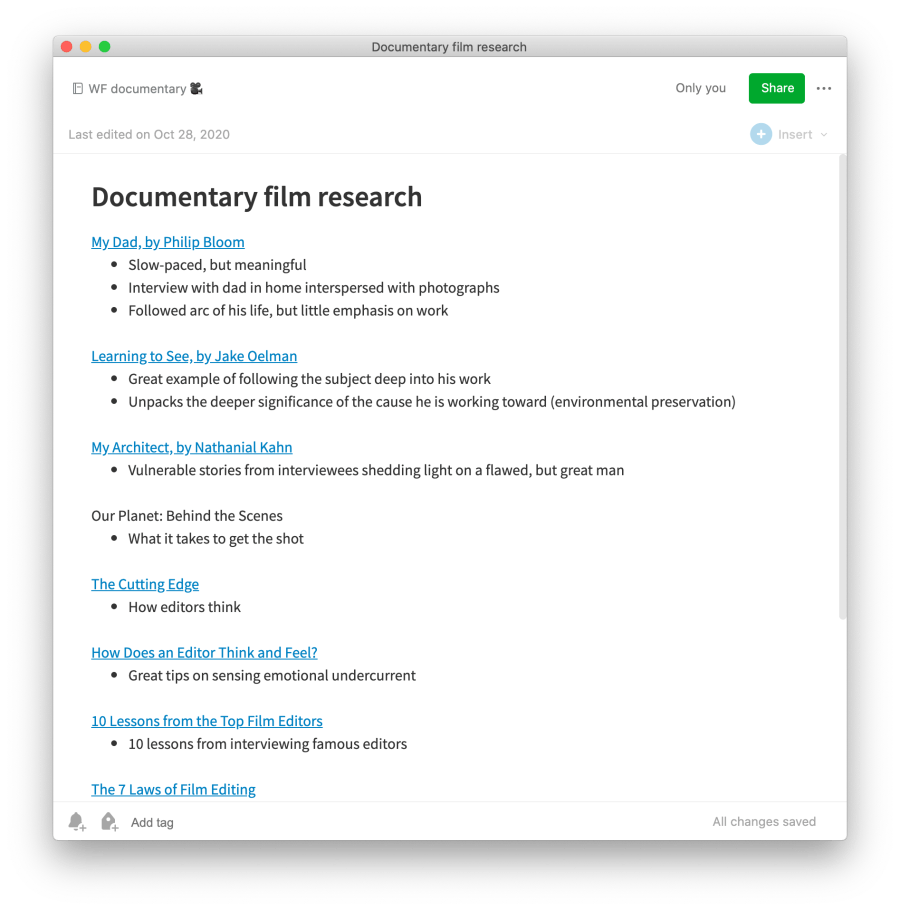

I knew right from the start that I would need a lot of exposure to good filmmaking. I had watched many documentaries throughout my life, but now I had a completely different motivation: to borrow the parts I liked and avoid the parts I disliked.

I polled my followers on Twitter and Facebook for recommendations of good documentaries, and within a few hours had several dozen. The popularization of video streaming services has made an endless variety of documentaries available to us at the click of a button. They don’t get as much attention as the latest hit series, but we’ve never had such easy access to the world’s best documentary films. Or as many options for distributing our own.

I put the list of film recommendations into a note, and over the next few weeks drew from this list for my evening watching, instead of the usual endless Netflix browsing. I noted the takeaways from each film below the title using bullet points:

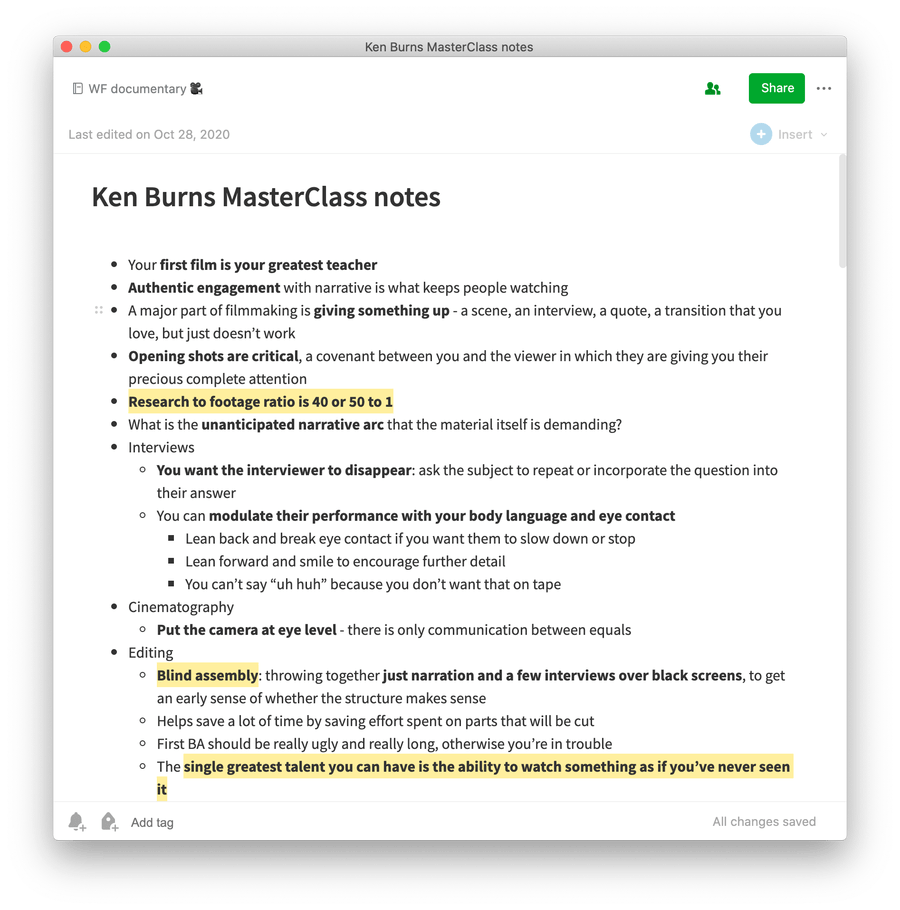

I also decided to take an online course on filmmaking for more structured learning. I was delighted to discover that Ken Burns, one of the filmmakers I most admired, offered a class on documentary filmmaking on the Masterclass platform.

It only took me a couple days to watch the videos and take notes on that course, and I came away with a wealth of practical knowledge and timeless wisdom that Burns had to offer. Here’s a sample of my notes, which I returned to time and again as my experience grew:

From the very beginning of the research phase, I was already capturing footage. I turned on my camera and started filming anytime I was with my family, or when I had some downtime. I experimented with new angles, tried all the buttons, played with all the settings, and played back clips on my computer to see how they came out.

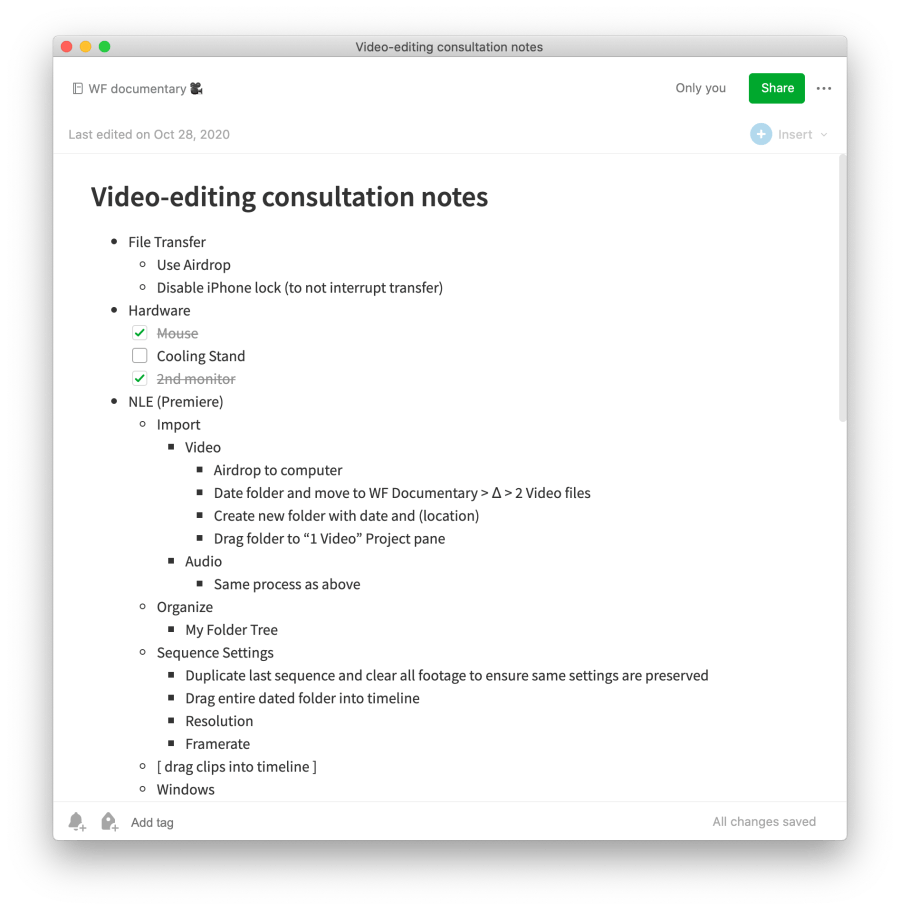

Once I started editing my footage in Adobe Premiere, I quickly realized that I would need to learn how the program works. I watched some free videos on YouTube, but knew that being able to ask questions of someone would help me move a lot faster. I hired a friend of mine, Joshua, to meet with me on Zoom and help me through those roadblocks.

Join the Forte Labs Newsletter

Join 40,000+ people receiving my best ideas on learning, productivity, & knowledge management every Tuesday. I'll send you my Top 10 All-Time Articles right away as a thank you

Subscribe

Premiere is an intimidating tool. It bristles with buttons and switches and toggles on every square inch. It is made for professional videographers and filmmakers, and thus offers a staggering array of the most finely tuned capabilities.

Luckily, almost as soon as Joshua and I started going through those options, I realized I would only need to know about 10-15% of Premiere’s features. I had no need for sophisticated video or audio effects, or stitching together multiple camera angles, or adjusting the exposure or color correction (thanks to the iPhone’s brilliant built-in image algorithms).

I only ended up doing three 1-hour calls with Joshua over the course of 6 months, plus a couple other short troubleshooting calls much later when I accidentally messed up my audio tracks.

Here are my notes from our calls:

I also saved a couple notes on potential topics for future exploration, such as how to organize large amounts of footage, how to do video transcription, and tips on how to interview one’s parents.

That was the extent of my research!

In the past, it would have been necessary to dive deep into the technical details of video formats, compression types, frame rates, lighting equipment, audio bitrates, and on and on.

With so much of that complexity now abstracted away behind the lens of my smartphone camera, I was left with far more time for the parts I really cared about: how to ask penetrating questions, how to construct a scene, how to tell a story, how to pack an emotional punch.

Even now, I barely understand most of the technical aspects of filmmaking. It’s simply not needed to get started anymore.

STAGE 2: PLANNING

My default approach to almost any project is to execute it in a “bottom-up” way.

What does that mean?

Instead of spending tons of time upfront creating detailed plans that might have nothing to do with reality, which would be a “top down” approach, I prefer to start taking action as soon as possible, and then see what kinds of plans emerge organically.

This project was no different. In fact, the very first shot I ever took ended up becoming the opening shot of the film. How’s that for getting right into the action!

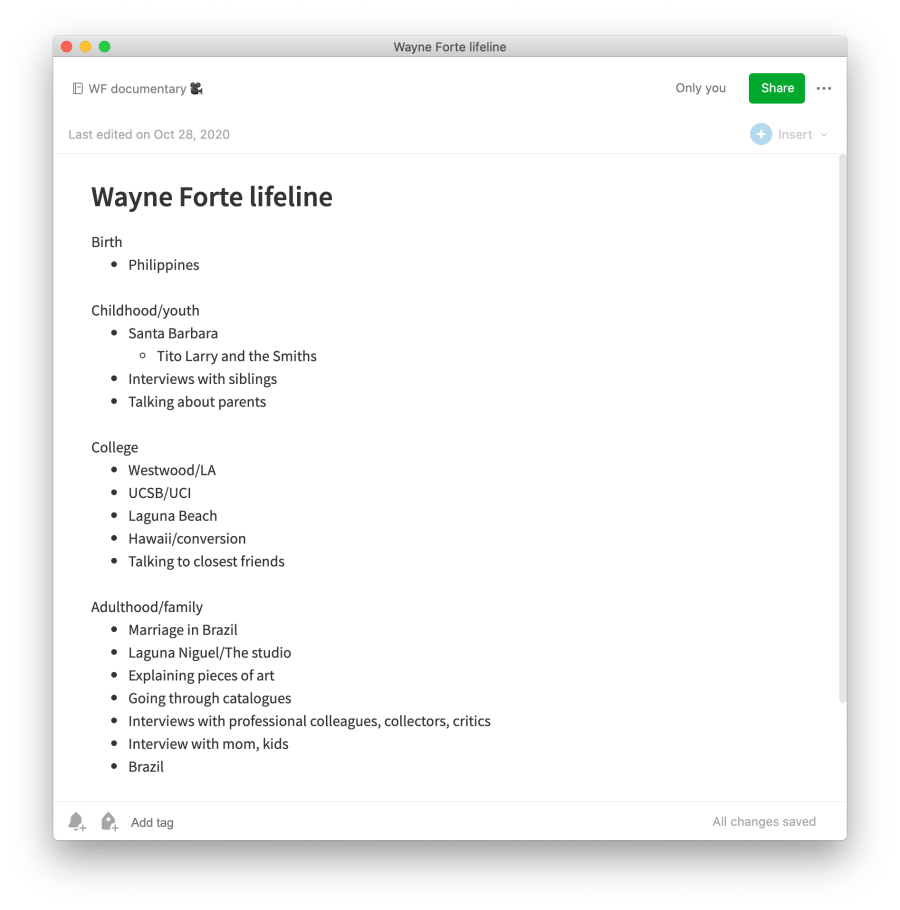

My planning was thus very light, and almost always done in the midst of filming. For example, I made a bulleted timeline of my dad’s life to make sure I was covering each of the major stages.

Even a short, casual list like this one sparked ideas for people I could interview, places to visit, and questions to ask. I then recorded those new ideas in a separate note, so I had a quick reference and checklist of shots still left to take.

Much later on in the editing stage, I realized I could insert photos into my film, using the classic “Ken Burns” effect of slow panning. I whipped up a note with ideas of photos I could look for, which again served as a handy reference as I went through old photo albums.

These quick, lightweight planning methods provided me with a tremendous amount of direction without bogging me down in bureaucracy. The notes I’ve shared above took mere minutes and served as critical touchstones every time I decided to take out my camera.

STAGE 3: FILMING

As I said before, filming was not a specific stage. It took place throughout the project, from the first day I decided to commit to it, to almost the very week it was screened. But I’ll consolidate all the notes I found most useful here to give you a window into how I used them.

Most of my filming-related notes were made up of tips and guidelines to follow. In the heat of the moment, with precious seconds passing by, I needed to be able to look at a single list or risk being completely thrown off track.

For example, I created this note to summarize the most important settings for my wireless microphone, the Zoom H1n.

It includes the “need-to-know” settings at the top, and pictures of the entire manual toward the bottom in case I needed to find an obscure setting. This is a great example of how useful it can be to create a succinct summary of a body of knowledge, while also keeping the full details close by in case you need them.

I made a similar checklist of “filming tips” to run through every time I turned on my camera, to make sure I didn’t miss a critical step.

STAGE 4: EDITING

Similar to filming, I didn’t wait long to start editing. I knew from experience that the best learning would happen when I tried to take one “slice” of raw footage all the way to a final product, so I attempted to do that as early as possible.

And I was right: only by seeing the footage on a large screen, sitting back and imagining how they would feel to an audience, did I gain fundamental insights into how the original footage could be made better.

Things like how long to linger on someone’s face as they’re speaking, where the cut between shots should go, how fast to pan across a landscape to make it engaging but not too quick, how high or far away from a subject to hold the camera, etc.

It’s difficult to put this kind of tacit knowledge into words. Which is why it can only be gained through experience. It’s an endless list of micro and macro-adjustments that no YouTube video or textbook or course could teach me. I had to make every mistake (in some cases several times) to understand these principles for myself.

“...gut feeling is not a mysterious force, but an incorporated history of experience. It is the sedimentation of deeply learned practice through numerous feedback loops on success or failure."

– Sönke Ahrens

Let’s take a look at the notes I used in my editing.

This note of “editing tips” was my checklist each time I sat down to import and edit a new set of clips. It ensured that I was using the same settings each time, organizing the footage in a sensible way, and remembering the decisions I had made previously.

Later I added some further guidelines as I moved into the editing stage as my primary focus, and uncovered some of the more advanced and subtle features of Premiere.

STAGE 5: SCREENING

After about 16 months of on-and-off work on the film, I was ready to schedule a screening. I knew I needed a looming date on the calendar to give me the accountability for that final push.

This was in the midst of the initial COVID surge, so I knew it had to be virtual. I did some research on livestreaming platforms, captured in this note, to figure out the best way of sharing the experience across the world.

Eventually I settled on YouTube Livestreaming as the best option, since it was widely supported and familiar to an audience that wouldn’t necessarily be tech-savvy.

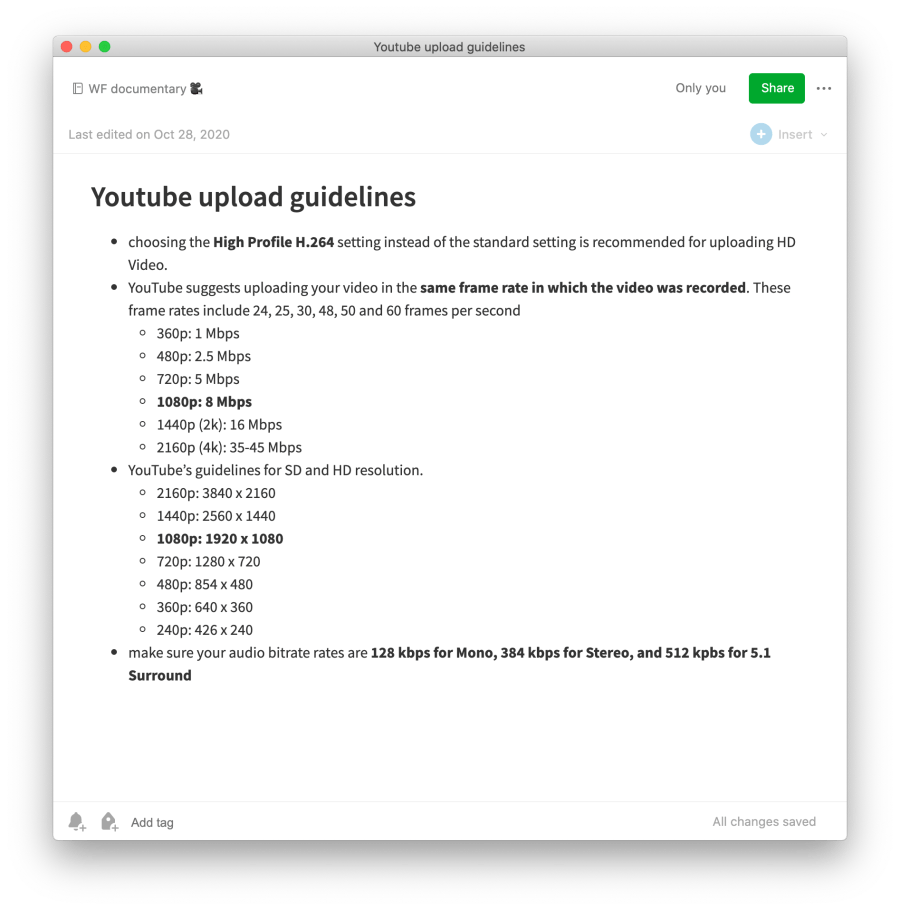

And then one day I realized that I could skip the complicated livestreaming altogether, and simply upload the film as a normal YouTube video using an unlisted link. At that point, all I had to do was follow the standard upload guidelines, which I took note of, bolding the parts that were relevant to me.

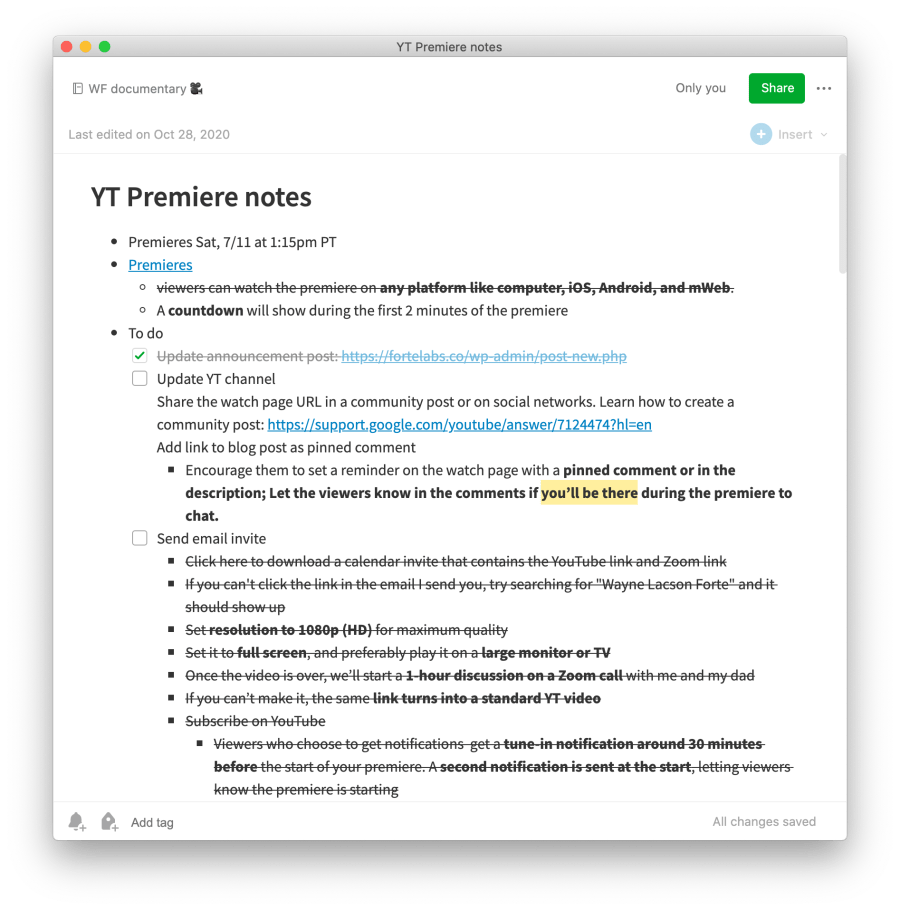

The virtual premiere ended up being quite an event, with more than 100 family, friends, and total strangers syncing up from around the world. I used this note to plan the event and write the email invite, which needed to explain how to access the screening from a wide variety of devices and which settings to use.

All the information needed to bring my film to completion is contained in the notes above, exactly as presented. It amounts to only 62.5 MB, the size of a large Word document.

This small collection of informal notes is a testament to the incredible leaps filmmaking has made in recent years to make the technology, skills, and knowledge of the craft widely available to anyone with the courage and dedication to make it happen. As well as to the impressive power of digital note-taking for learning new skills and executing creative projects.

Telling the story

Toward the end of this film project, I started creating a different kind of note. I saw that the story of the story – why I decided to do this project, what I learned from it, how I did it – was interesting within itself. These notes became the article you’re reading right now.

For example, I saved a research finding that “kids who know more about their family history had a greater belief that they could control their world and a higher degree of self-confidence.” This was the first piece of hard evidence of something I had long suspected: that knowing more about your past can directly impact your present wellbeing.

One day sitting at a sidewalk cafe in Mexico City where I lived, I had the crazy idea that I could teach a course on how to make a personal documentary. I wrote down this proposed curriculum, which I’ve kept on the backburner since then.

And I started noting down the first inklings of the “big picture” ideas that have led me to believe that personal documentaries represent a profound shift in democratized storytelling.

The final note

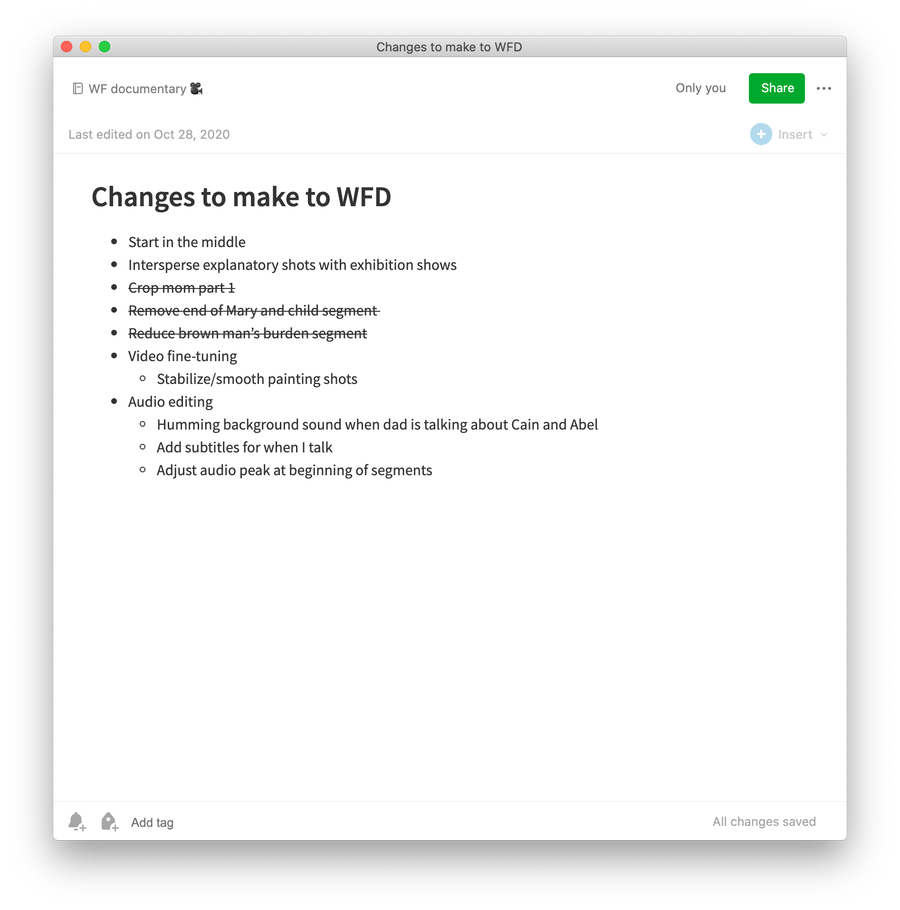

The last note I took was about future changes to make. Inevitably, as you share a creative work like this one that touches the lives of many people, the “casual suggestions” start coming in. People want a scene cut or added, they want you to interview just one more person, they want to correct something they said, and so on.

I knew that if I kept making these changes the film would never be finished. So I put them all in this note, knowing that if and when I wanted to make a new cut, all these ideas would be ready and waiting for me.

I want to emphasize that I didn’t know I needed most of the notes above until I actually created them. There was no grand master plan I was following. I got into action as quickly as possible, and captured learnings and insights in my notes as they came up.

What I Learned

Here are the biggest lessons I learned from the experience.

I WAS MORE PRESENT AND ENGAGED WITH MY SURROUNDINGS

One of my biggest concerns with starting this project was that I’d be less present in my life. I worried that I would obsess over looking out for opportunities to “get the shot,” instead of just enjoying everyday experiences.

I was surprised to find that the exact opposite happened.

I started to pay more attention to the little moments. The light reflecting off a dish as my mom placed it on the counter. The reflection in a doorknob as my brother reached to open it. The bubbles rising to the surface of a carbonated drink.

With my filmmaker’s eye, I started to notice that I was surrounded by little moments of beauty and poetry. As these moments became my creative medium, I started to appreciate them much more deeply. Time often seemed to slow down as I zoomed in on a particular scene, sound, or word.

PEOPLE RESPOND SURPRISINGLY WELL TO BEING FILMED

Another concern I had was that everyone around me would feel awkward being “on the spot” all the time. I didn’t want to be that annoying person who is constantly asking people to pose.

But once again, I found that the exact opposite was the case. I was honestly shocked how comfortable people were being filmed.

Virtually everyone I captured on camera was far more vulnerable than normal, because the camera gave them a “reason” to be vulnerable. They opened up and shared memories that I’d never heard. Something about the focused attention of the lens, like a closely listening ear, gave them permission to speak incredibly honestly about their experiences.

PEOPLE HAVE MORE MEMORIES AND STORIES THAN THEY REALIZE

If you ask one of your parents, “What was your happiest memory as a child?”, you’re very likely to get a flippant answer. Not because they don’t want to tell you – they do. But in the humdrum routine of daily life, there just isn’t usually an opportunity to get into such memories. It feels strange for both parties.

But when you turn on a camera, even if that camera is just a smartphone, suddenly everything changes. Suddenly they feel a responsibility to tell you the real answer. They are doing you the favor of “helping you with your film project.” They open up because they have an excuse to.

I often had the thought that I could have put up the camera and only pretended to film, and it would have been worth it just for the depth of conversation it made possible. I was shocked to hear so many new stories from people I’ve spent more time with than anyone else.

I don’t think we realize how deep of a well of memory each human being has access to. Everyday life doesn’t give us many opportunities to revisit those memories. But recording them does.

THERE IS AN ART TO INTERVIEWING

I initially had the idea that interviewing was essentially just asking questions. I would look at journalists and wonder, “How hard could it be?”

I quickly discovered that there is a subtle art to interviewing. I played a major part in the performance of an interview as the “director” behind the scenes. The subject gets to just show up and talk. I am the one that has to plan, prepare, listen, and react to wherever they want the conversation to go.

People tend to drop all kinds of hints about what lies underneath the surface – offhand comments that point to something deeper, inflections in their voice that signal a hidden emotion, shifts in body language suggesting you’re getting somewhere sensitive.

It was in the moments that I noticed those hints, and pushed a little, that magic happened. A comment as simple as “Say more” can unlock an exquisite outpouring. And I think that people secretly hope you’ll ask for more. We all want to be heard, but we don’t want to speak unless we know the other person is listening.

FILM EVERYTHING

I learned early on that it paid to “film everything.” I started out being very picky about what I captured. I thought I needed just the perfect light, the perfect audio conditions, perfect preparation, and the perfect state of mind to get it right.

But I soon noticed that a perfectionistic attitude caused me to miss out on valuable shots, which tend to arise spontaneously in the moment. Sitting down at my computer to review my footage, I realized that there was a world of difference between “footage I had” and “footage I didn’t have,” whereas the difference between “footage I had,” and “the perfect footage” was much smaller.

Having any footage at all was essential, so it was worth getting out my camera and hitting record even if I wasn’t sure what I was filming or why. The magic of editing is that even if there is just one meaningful phrase in an hour-long clip, you know you’ll be able to find it and use it.

There’s a parallel here to note-taking in general. If you wait until you know exactly why you’re writing something down, it’s already far too late. You have to capture it right in the moment, taking advantage of the natural serendipity of the moment. Listening to your intuition about what resonates can give you a shortcut to saving valuable material before your conscious mind even knows what’s happening.

In the end I had a 17-to-1 ratio of raw footage to final cut, which should give you an idea of just how much you need to record in the first place. Professional filmmakers often report a ratio of 40 or 50 to 1.

HUMAN MOTIVATION IS STILL THE BOTTLENECK

Initially I thought my takeaway from this project would be “See? It’s easy!”

But in retrospect that isn’t true at all. In fact, it took every skill in my toolbelt, every ounce of motivation, and a lot of support from others to maintain my momentum and persevere until the end, even with all the technological breakthroughs we’ve seen.

I estimate it took me about 100 hours of work spread over 16 months, broken down approximately as:

- 10 hours: planning, researching, coordinating

- 30 hours: filming (spread out over about 20 filming days)

- 10 hours: learning, testing, experimenting

- 50 hours: importing files, organizing, editing

Instead, my takeaway is “It’s easier than ever…but still very hard.” That said, I was also learning to make a documentary at the same time I was making it. For the next one, I’ll be able to reuse a lot of what I learned and use my time much more effectively. I estimate I could do it in half the time.

The decisive factor in any creative project is still the human being – their fears, desires, anxieties, limiting beliefs. It’s always been that way, and always will be. I found myself relying heavily on my productivity skills, capturing the many open loops for edits I had to make and tracking them through to completion. I also relied heavily on my note-taking skills, saving all sorts of tips and ideas and guidelines as you saw in the notes above.

I have no idea how I could have completed this project without having all the relevant information saved outside my head. I could only afford to spend a day or two at a time working on it in the midst of my other responsibilities, which meant that every time a bit of free time opened up I had to be able to jump into my notes and pick up right where I left off. I don’t know any other way of doing that besides keeping the “work in process” outside one’s head.

We are living in the midst of a creative renaissance, with every creative medium rapidly becoming more affordable, accessible, and shareable. But in some ways this makes it harder for us to create our own works – we are exposed at all times to the very best creators, artists, writers, musicians, and dancers in the world.

How could we compete with all that? What do we have to say that hasn’t already been said? It’s so much easier to give up our ambitions and spend our days scrolling through the accomplishments of others.

We could try to optimize how our brains work to make the creative process more efficient. We could set rigid schedules and work up the self-discipline to churn through our To Do lists. But I think that’s a mistake. Creativity requires randomness and serendipity, and we run the risk of optimizing the creativity right out of the experience.

I have another idea: we remove the bottleneck. Take the human out of the loop as much as possible, replacing her with a system of knowledge management. Such a system never sleeps, remembers all details perfectly, can connect and communicate with other digital tools, and preserves everything she’s working on so she can step away when life gets crazy and come right back to it later.

IF A STORY ISN’T SUCCINCT, IT’S INVISIBLE

A few years back, my mom paid for a service to digitize several decades of home videos. She shipped off a few boxes of tapes in multiple shapes, sizes, and formats, and a few weeks later we received a login to access them via a convenient web portal.

But even with that convenience, we’ve rarely gone back to watch those videos. There are just too many of them – perhaps 300+ separate videos adding up to hundreds of hours of footage. In most of the clips I’ve seen there’s not much happening most of the time. The exceptional moments are rare and unexpected by definition.

It would take a serious effort to watch, curate, organize, label, and condense those best moments into a compilation video of 1-2 hours. Yet I don’t know of any other way to make those memories accessible in the future. Without such a succinct artifact, I doubt we will get much value out of this treasure trove of precious memories.

Here is what I’ve realized: even if records exist, if they’re not organized and condensed and presented in an accessible way, they might as well not exist. The effort required to weave together disparate clips with skillful editing, transitions and effects, audio and music into a captivating story isn’t a nice-to-have. It is essential to allow that story to survive through time in a way that it touches the lives of future generations.

But time and attention are more scarce than ever. Which makes me wonder whether, despite the many thousands of photos and videos we’ll capture digitally over our lifetimes, we’ll really have as much access to those in the future as we think.

Making our information digital was supposed to mean that we never lost anything again. But in making it so seamless and easy to just “save things in the cloud,” our technology has masked the very real effort required to create artifacts that stand the test of time.

Is it possible that the surplus of digital information is leading us toward a poverty of memory? That our lives will be no better documented than our parents or grandparents, and maybe not even that well?

VIDEO WILL BE THE COMMUNITY GATHERING OF THE FUTURE

Working on this project in the midst of the COVID pandemic, I was struck by how meaningful of an experience it was to watch this film together.

We all have an essential human need to come together – to grieve, to celebrate, to express ourselves, to resolve conflicts, to share our feelings. This need hasn’t disappeared in the digital era. It’s been channeled and amplified by “social” networks, and not usually in a healthy and productive way.

When I look out across the social media landscape I see a desperate, aching need to connect with each other. In the absence of positive connection, people will turn to destructive connection. That is how deep our need for connection goes.

Part of my motivation for this project was to see if I could create a true community experience online. I’d lived abroad in various countries for years, and so maintaining my community of family and friends had always been a preoccupation.

It succeeded beyond my wildest dreams. Even scattered across the country and world, the shared experience of immersion in a story created a “living room” experience. We all were watching something, knowing that others were watching it, knowing that they knew we were watching it, and so on in a reciprocal web of thoughts and emotions.

The essential ingredients for virtual community seem to be:

- An artifact to gather around and spark conversation (the film)

- A strong pull of timeliness (an event happening at a particular time at a particular “place”)

- A reason to come: the ideas and insights and realizations promised by the film

- A pre-existing community: my family, friends, and community around my work at Forte Labs

- A host (to welcome people and “manage the room”)

- A way to share reactions and feedback (comments during the YouTube Premiere, and a followup Zoom call we did right after)

Video is the most widely available creative medium, as well as the most immersive. It is unique in allowing groups of people, even spread apart in different locations, to be immersed together. I’m fascinated by the potential of using video-based storytelling to bring people together in an era of social distancing.

No longer do you need an MFA or Hollywood internship to tell stories to a global audience.

We are living in a new world of democratized storytelling, but it is only those who take the time to turn their stories into tangible creative works who get a vote.

Download Resources

Because you’re a Praxis member you can download the full content of all 21 notes shown above in both Evernote and Notion format. You can borrow from what I learned, explore how I construct notes, and even use my notes as a template for your own video project.

Thank you to Fred Esere, Shayna Englin, George Gusewski, Carlos Esteban Balderas, and Daniel Chapman for their feedback and suggestions on this article.

Find Out What

Comes Next in Tech.

Start your free trial.

New ideas to help you build the future—in your inbox, every day. Trusted by over 75,000 readers.

SubscribeAlready have an account? Sign in

What's included?

-

Unlimited access to our daily essays by Dan Shipper, Evan Armstrong, and a roster of the best tech writers on the internet

-

Full access to an archive of hundreds of in-depth articles

-

-

Priority access and subscriber-only discounts to courses, events, and more

-

Ad-free experience

-

Access to our Discord community

Comments

Don't have an account? Sign up!