An AI Might Have Written This

Writers are using apps like Sudowrite and Subtxt to craft essays, short stories, and screenplays

As a writer collective, we’ve had AI on the brain—from my last piece on AI companion bots to Evan’s excellent essay on the AI value chain to Nathan’s exploration of the infinite AI article.

Every has also been building Lex, a word processor with AI baked in. I started working on this piece before we launched Lex, but testing out this tool (among others) has shaped my perspective on the role of AI writing assistants for creatives. Try it for yourself: watch the demo and sign-up to join the waitlist (Every’s paid subscribers have priority access, so subscribe to skip the line).

In 2016, filmmaker Oscar Sharp and AI researcher Ross Goodwin created an experimental short sci-fi film written entirely by a neural network. Sunspring, the futuristic space comedy generated by the machine, was the result of an AI trained on hundreds of sci-fi TV and movie scripts. Its viewers noted that the actors in the film did a phenomenal job spouting gibberish, English words strung together with little meaning.

A year later, author Stephen Marche worked with two researchers to help him create the perfect science fiction short story, using an algorithm they had developed. It was trained on 50 short stories Marche himself wished he had written. Assembled by algorithm, the story fell apart under scrutiny from human reviewers who noted it was “full of unnecessary detail” and “sentences that don’t actually hold up when you read them carefully.”

More than six years later, in the midst of an AI boom, artificial intelligence has yet to invalidate human creativity. Writing generated by AI alone remains obvious or “off,” even with the development of Open AI’s novel GPT-3. Examples of creative fiction generated with GPT-3 are undoubtedly impressive, but even Open AI’s CEO has argued the response to the technology is overhyped. AI writing tools can’t yet produce cohesive scripts or books that replace the best authors and screenplay writers.

But AI is mounting its case as a useful writer’s assistant, a tool writers are choosing to augment their own creativity. Indie fiction writers are using AI assistants to write their novels faster, and a New York Times best-selling author, April Henry, is using AI to help generate story ideas. For now, AI writing assistants promise creatives expanded imagination, a tool to serve as creative complement rather than competition. The dynamic remains man and machine, rather than man versus machine.

After selling the company he founded, Amit Gupta turned to writing science fiction. He wanted to craft stories that advanced a utopian vision of technological progress, a contrast to the dystopian depictions that dominated the genre. Writing proved to be rewarding, but challenging. As a photographer, Gupta had a suite of software tools he used to improve his snapshots. Yet writing remained a process limited by manual iteration of letters and words, bound by the time required to brainstorm and arrive at new ideas.

It was the heavyweight nature of the writing process that inspired Gupta, along with his co-founder and fellow science-fiction writer James Yu, to create Sudowrite. When OpenAI’s GPT-3 tool was released in 2021, Gupta and Yu saw the technology's potential for helping writers brainstorm story ideas and advance plotlines. “Our hope is that Sudowrite starts to feel like a buddy next to you. Who can brainstorm with you, and who you can bounce ideas back and forth with, and who's just always available to you,” says Gupta. “The next few years especially will unlock a lot of possibilities in this space.”

One of those possibilities is changing how the writing process unfolds. When you can’t find the right word, you consult a thesaurus for options. If a grammatical rule evades you, a tool like Grammarly can be of aid. But when an idea, concept, or string of sentences fails to tumble onto the page, we sit stuck and often give up. AI writing tools promise to bust writer’s block, generating lines of text to inspire our ideas and provide creative direction. Or, if the lines work, they can be incorporated.

“I don’t use it to generate words, more for giving me ideas and provocations for directions that I should go,” says Gupta on his own writing process in Sudowrite. “I also use it to help with the outlining process. Once I get a really solid outline, and I feel like I know what the characters are about, what they care about, what their motivations are, and what's going to happen to them, writing becomes easy for me.”

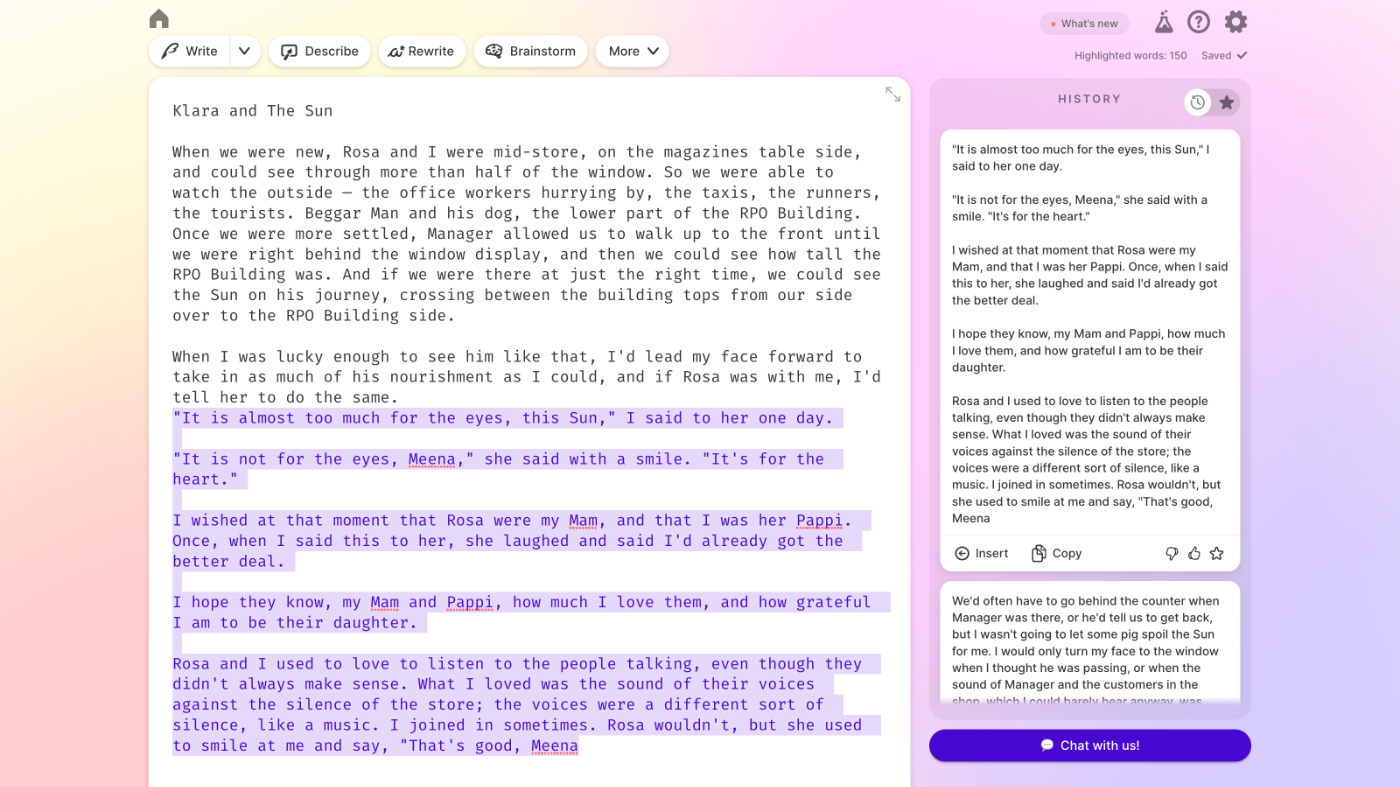

When you get stuck while using Sudowrite for your fiction, non-fiction, or poetry, the AI suggests writing for you, ostensibly removing your block through auto-complete. By first writing a few lines of your own—or adding a block of your own prose—Sudowrite mimics your style, writing in your voice and tone, and adding predictive paragraphs for you. For those who want to incorporate rich descriptions in their writing, the tool also automates descriptions using the five senses as a guide.

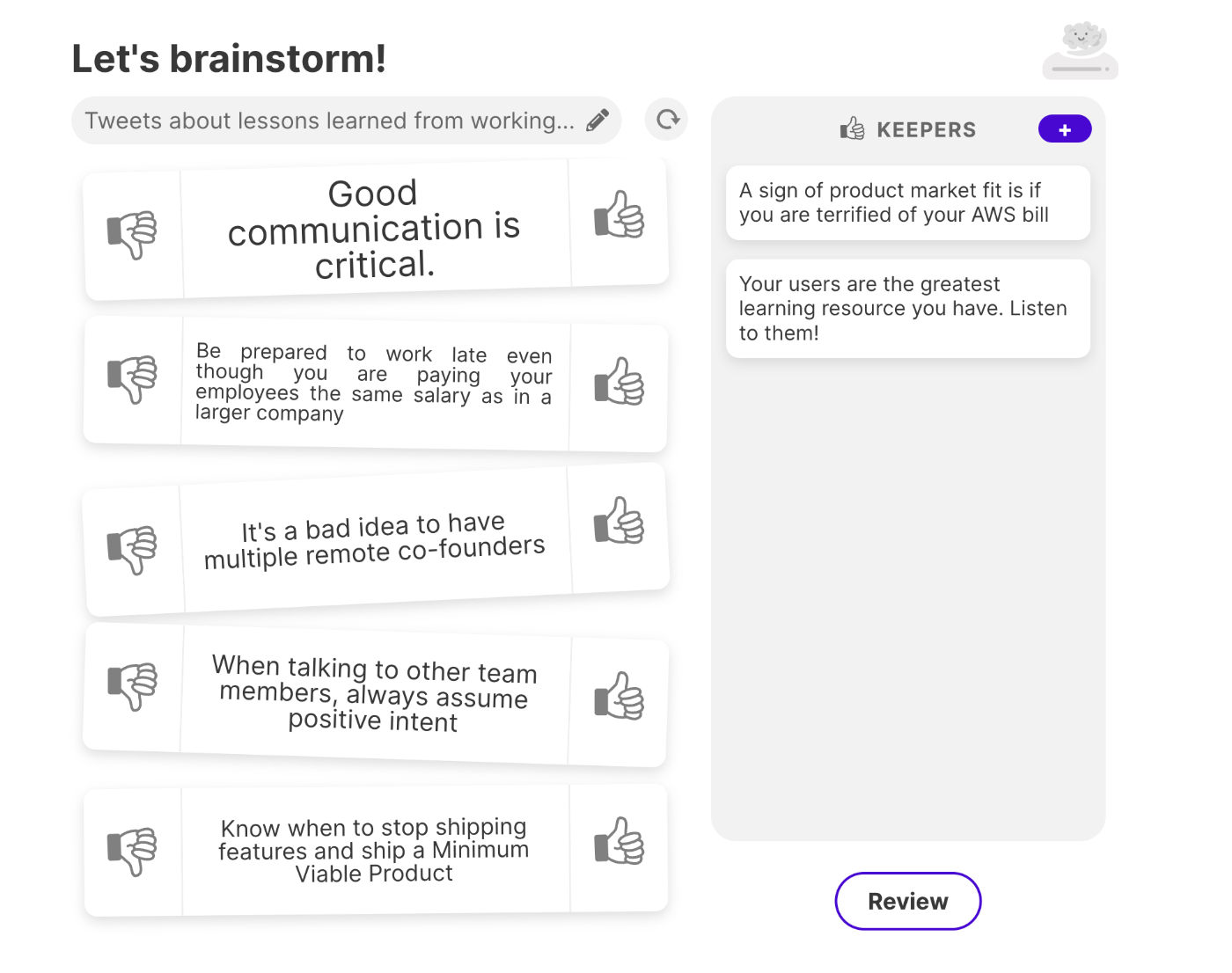

In addition to adding words to your page, the app’s features include a tool for brainstorming everything from character dialogue to plot points. With the collection of the world’s knowledge at its fingertips, Sudowrite can also reference the work of other relevant researchers and writers—providing its users with a jumping point for their own research. The app can also rewrite your paragraphs for you, giving you more options to further edit. In short, Sudowrite is changing the nature of creation.

Sudowrite and other AI writing tools see themselves in a long line of technological advancements heralding bold forms of creativity, dating back to the advent of writing itself—tools for thought, changing how we think and, maybe, what we think about. They’re thought partners, rather than creative adversaries. They won’t spit out flawless phrases, but they will help you get closer to your own version of perfection.

With a thesaurus, a writer gets to choose the word from a list of synonyms, selecting the one that might most meaningfully roll off a character’s tongue. With Grammarly, an essayist can break a grammar rule for effect, ignoring the tool’s red warnings. Similarly, AI writing tools provide writers with possibilities they can discard or build upon. In all cases, tools are assisting human creativity, not replacing it.

AI writing tools have also been useful for Jim Hull, a long-time animator-turned-story-consultant who has worked at Dreamworks across films like How to Train Your Dragon, Bee Movie, and Shrek 2. He merged his love of software development and storytelling to create Subtxt, an AI writing tool with a built-in predictive narrative framework. His tool helps fiction writers advance their own plots and develop outlines using the Dramatica narrative framework.

The tool also pulls in the arcs of over 500 popular plots, like Top Gun and the first season of Loki. Hull runs a cohort-based course where he teaches students how they can use AI to improve their storytelling—from fleshing out characters to perfecting plot points. He suggests that tools like Subtxt can help anyone become a better, more prolific storyteller, citing projects that have used the tool in their development including Oscar-candidate documentary Eternal Spring, the Tangled television series, and the Blacklist script Neither Confirm, Nor Deny.

“Writers finally see why they always went into writer's blocks, or why they go halfway through the story, then stop, not sure where to take it,” says Hull. “The best part of the AI is that it’s engineered to be a teacher and a collaborator.”

Every dystopian vision of the world has an equal and opposite utopian imagination. The dark version of AI includes novel technologies rendering entire fields obsolete—Midjourney and DALL-E bringing the end of illustrators, GitHub Copilot the demise of software developers, and Sudowrite and Subtxt the death of authors, to name a few. Given so much of the storytelling in this vein, it’s not hard to imagine humans being outsmarted and overpowered by our own former assistants. But many creatives embrace these tools and see their democratizing potential.

Gupta describes AI writing assistants as a force for good that will create more writers—and better ones. He notes that Sudowrite is not a tool meant to write for you, but rather help you come up with new ideas and improve your writing.

In the future, as AI technology advances enough to write stories of its own, he suggests that writing will still require a human touch to remove AI fingerprints. “You're not going to like the stuff that just comes out of it as stock, the stuff that feels too shiny, too rounded, too inoffensive, too easy,” he says.“You'll want the human to go on and make it their own.”

AI writing tools and assistants on the market still require a human at the helm. AI interfaces frequently generate quotations from public figures they’ve never actually uttered and advance arguments in a direction that’s imprecise or untrue—requiring vigilance and fact-checking by the human user. You won’t yet find a tool that writes an entire novel or spits out an article that doesn’t require warm-blooded editing.

Even so, fear about the AI revolution leading us towards mass unemployment—in both blue collar and white collar fields—persists. In some cases, job replacement seems to be the aim. In its marketing, an AI tool called Jasper claims that “artificial intelligence makes it fast and easy to create content for your blog, social media, [and] website…” while Rytr advertises the ability for an AI writing assistant that “helps you create high-quality content, in just a few seconds, at a fraction of the cost.”

Certainly, one interpretation of this tooling explosion is the beginning of the end of the writing profession. On the other hand, AIs may automate the parts of the writing process we once thought of as essential. How might the work of a writer improve if we stopped romanticizing the blank page, using AI prompts as a jumping point for our best ideas instead? If an AI can build a compelling outline—of a script, essay, or short story—might the extra time afforded to a writer be better spent on improving a narrative? What if the writing process was multi-player instead of single-player, and every piece of writing was a collaboration instead of a singular effort? What if writer’s block became a concept of the past? It’s possible that the processes we currently see as core to the writing process are actually dampening our creativity.

Hull saw this precise creative dynamic play out as an animator transitioning from 2D to 3D animation. “It got rid of all the mundane and nightmarish [tasks], like doing overlap and follow-through,” he says. “You just hit a button, and the computer does that. So, what happens, then, is you have more time to spend on the important stuff, like the performance.” Hull argues that the level of storytelling we see in animation today would not be possible without the tools that automate much of the rote tasks in film animation. “Pinocchio is beautiful. And 101 Dalmatians has gorgeous animation, right? But it’s not anywhere close to Encanto. And that's a really good thing.” He believes we’ll see this happen in the world of writing.

Gupta cites the wide use of smartphone photography, existing alongside a class of professional photographers, as a similar analogy. “If you get married, you're probably going to still hire a wedding photographer, even though everyone's got a smartphone,” he says. “You might see something similar happening with writing. When it's important, you're going to want someone who's really good. That doesn't mean they don't use these tools, but they're probably really good at using them.” Expertise in every creative field will increasingly be redefined as people who can best work with technology to create the best results.

Reading a piece like this, it will soon be impossible to tell where the human author ends and an AI begins—in fact, it already is. For writers, AI writing assistants may become a partner for crafting poems, short stories, books, and screenplays with less stress and in less time than before. AI for producing more content for audiences, and doing so faster, is an uninspiring aim in a world with an excess of content. But, if AI can truly work with our thoughts to expand our capacity for creativity, we’ll wonder how we ever lived without it.

Thank you to Rachel Jepsen, who edited this piece.

Find Out What

Comes Next in Tech.

Start your free trial.

New ideas to help you build the future—in your inbox, every day. Trusted by over 75,000 readers.

SubscribeAlready have an account? Sign in

What's included?

-

Unlimited access to our daily essays by Dan Shipper, Evan Armstrong, and a roster of the best tech writers on the internet

-

Full access to an archive of hundreds of in-depth articles

-

-

Priority access and subscriber-only discounts to courses, events, and more

-

Ad-free experience

-

Access to our Discord community

Comments

Don't have an account? Sign up!

I actually watched Pinocchio recently and really appreciated the intention behind every hand drawn frame. The pacing was so pleasant I found the wisdom under the themes shined through so much more than modern animation like Encanto which just felt like culture was constantly punching me in the face. The amount of detail everywhere never allowed me to focus on anything.

Maybe unpopular opinion but there is something much more enduring about old Disney and I think it’s actually BECAUSE they had to draw every frame intentionally.