We all want to know how we’ll feel in the future. If we had perfect information about how decisions in our lives would affect our emotions, we might do a lot of things differently. That’s why, as they say, youth is wasted on the young.

I remember dancing in a glass-enclosed conference room when we got our first acquisition offer. It was 2014, and the company I’d started, Firefly, was a small team and had just started to bring in meaningful revenue. I hung up with Public Live Chat’s (a pseudonym) corp dev guy, queued up AWOLNATION’s song “Sail” on Spotify, and wriggled as un-self-consciously as a Hasid in prayer. Suddenly, at 22, I was faced with one of the biggest one-way door decisions of my life.

Six years later, I remember deliberating endlessly in late-night phone calls with Nathan about the decision to raise money for Every. It was the heady days of the creator economy, we were growing like crazy, and startups were pulling down massive seed rounds. Did we want to put the company on a venture path? Or should we heed the blood-soaked history of venture-backed media companies and stay bootstrapped?

Most decisions in life are reversible. But some are one-way doors. Jeff Bezos talks about these:

“Some decisions are consequential and irreversible or nearly irreversible—one-way doors—and these decisions must be made methodically, carefully, slowly, with great deliberation and consultation.”

If you’ve lived any length of time you’ve probably faced a few of these one-way door decisions yourself. Sometimes you’re choosing between two new options: Get a job or travel the world. Sometimes you’re choosing between the status quo and something radically new: Stay in a relationship or leave; climb the corporate ladder or quit to go all in on a startup.

The decisions we make are the lives we build. One-way doors are the entrance to an entirely new and unfamiliar part of our paths.

In business, there are many inputs to a one-way door decision. There are practical considerations, strategic considerations, and economic considerations. But an important variable in any decision is: How will we feel, personally, when we cross the threshold of that door? Will we regret it? Will we be happier?

Predicting how we’ll feel about a decision is something that we repeatedly get wrong. We think things will make us happy when they won’t. We miss opportunities that would change our lives because we’re too afraid to try them out.

Worst of all, our projections about what might make us feel happy or satisfied are key inputs to our economic and strategic decision-making. How many people raise money or sell their startups expecting to feel happier, only to find a deep depression on the other side?

In short, refining our ability to predict our future state is critical.

AI is an incredible tool for this kind of decision-making. It can simulate us—our personalities, our thoughts, our emotions—and reveal what that simulated version of ourselves might feel and think in different circumstances. It allows you to walk through a one-way door like a caver: wearing a sturdy harness knotted to a rope tied to a rusted stake. You explore the darkness fearlessly and follow the fastened rope back out.

I’ve been using AI to help me make one-way door decisions and predict my future state. For obvious reasons, I don’t want to talk about present-day decisions. But I do want to walk you through how it could have affected one of my historical one-way door decisions, so you can see how powerful it might’ve been.

AI-assisted one-way door decisions

When we were deciding whether or not to raise money for Every in 2020, I was doing a lot of journaling in the then-red-hot note-taking app Roam Research. I was writing about things like: What are the pros of raising? What are the cons? What are my fears and how realistic are they? What could work about raising money for this business?

The nice thing about this journaling habit is that I have all of the entries. I know exactly what I was thinking at the time. So I grabbed a bunch of them, threw them into Claude, and asked it to pull out the patterns:

“Here are a few journal entries about whether or not to fundraise for Every. Can you help me find patterns that can help me make a breakthrough? Be honest and direct. Be specific, use examples.”

Here’s what I got back (lightly edited for clarity and privacy):

“Based on the journal entries you provided, there are a few key patterns and themes that emerge:

- Fear of losing control and autonomy by taking outside capital. You worry that having investors will make you feel obligated to hit metrics and strain for growth in ways that make you uncomfortable. You want to avoid feeling terrible and being "behind the curve" constantly. The idea of taking investor money is triggering a strong "NO" reaction in your body. You seem to want to maintain control and optionality, focusing on craft and writing.

- Desire to build something on your own terms. You are drawn to founders like Andrew Wilkinson, Nathan Barry and the Basecamp founders who built profitable businesses they own and control. You want to create your own "weird wonderland company" and having too many investor expectations feels at odds with that.

- Changing and uncertain feelings. Your feelings seem to oscillate a lot on this topic and you acknowledge not being 100% sure how you feel. The VC-backed vision sometimes resonates but other times feels off to you. You are trying to stay open while also listening to your intuition.

In summary, the conflict between an investor-driven, high-expectation growth path and a more organic, craft-driven, founder-controlled approach is the core tension causing you stress. At the same time, you acknowledge that company-building inherently involves some discomfort and that investors aren't necessarily bad. Staying open to paths where you maintain sufficient control/autonomy while still having support to build something great seems wise.”

When I read this, my jaw dropped. It’s such a mirror into my mind. I could see things in it that I felt but, at the time, hadn’t been able to put into words. The clarity about my fears and desires is striking, and it’s a far cry from the ambivalent mess on display in the raw entries I fed it.

Simulate future journal entries

Next, I asked Claude to write future journal entries. First, I asked it to journal about how I would feel if we raised a small round for Every (which we did):

“Based on these journal entries, please write a new journal entry as me with how I’d feel if we raised a small $700k round for Every. Try to simulate me and my personality as accurately as possible.”

Here’s how it replied (again edited for clarity and privacy):

[[Every Journal]]

We decided to raise a small $700k round for Every, and I have to admit, I'm feeling a mix of emotions about it. On one hand, I'm excited about the possibilities this funding opens up for us. It's a vote of confidence in what [[Nathan Baschez]] and I are building, and it gives us some runway to really focus on creating something amazing.

At the same time, I can't shake this lingering unease. I keep coming back to this vision I have of building a company on our own terms - something that reflects our unique perspectives and values. I worry that even with a smaller round, we'll still feel that pressure to hit certain metrics and make decisions that prioritize growth over craft. (The journal entry continues for paying subscribers.)

This is strikingly similar to what I actually wrote about our fundraise in my journal, which you can read (for paying subscribers). It also predicted exactly what happened: Even though we raised a small round, I did feel a lot of pressure. It caused me to make a lot of decisions—like deciding not to write anymore so I could run the business—that stagnated our growth and made me less happy.

It gets even more interesting, though. I asked Claude to write about how I would have felt if we hadn’t raised money:

“Based on these journal entries, please write a new journal entry as me with how I’d feel if we didn’t fundraise at all. Try to simulate me and my personality as accurately as possible.”

Claude does its best to pick up the patterns in my feelings and reactions, and tries to simulate how I would feel in a hypothetical future:

[[Every Journal]]

After a lot of deep conversations and soul-searching, we have decided not to fundraise for Every right now. And I have to say, as soon as we made that decision, I felt this huge wave of relief wash over me.

It's not that I'm totally opposed to the idea of fundraising ever, but right now, it just doesn't feel aligned with what I want to build. I keep coming back to this deep desire to create something that is truly an expression of our unique perspectives and values - a "weird wonderland company" as I've been calling it in my head. (The journal entry continues for paying subscribers.)

I think Claude is right. I’m glad we raised money for Every: It’s given us a cash cushion and a bunch of great investors on our side who can help us when we need it. But if I’m honest, it ended up being a distraction from what I really wanted to do with the business. I think I would’ve felt a tremendous sense of relief if we’d skipped it entirely—and we’d probably be at a similar (or possibly better) place in the business.

Reading this now, I feel a little bit of grief. Years ago, hiding behind one of the doors of that decision was a wave of relief that probably would’ve been best for the business. I just couldn’t quite see it at the time.

Why it works

Large language models are excellent personality simulators. If you give a language model a prompt about what kind of personality to mimic, it will reliably answer your questions in that style. It can even produce long-form writing consistent with a given personality type. (For more on this, I wrote about it in "Personality Simulation Is Coming.")

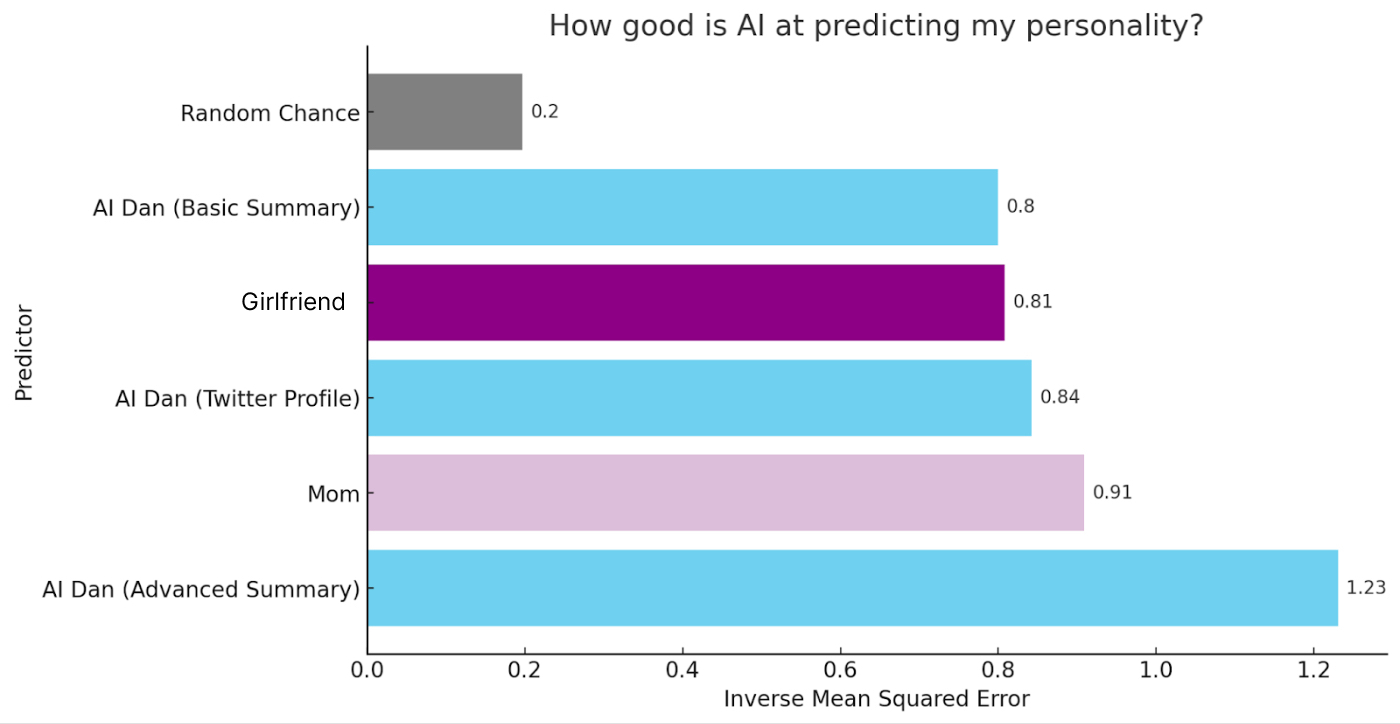

Language models can also take on your personality. For example, I asked GPT-4 to read my tweets and construct a personality profile from them. Then I had it take a personality test as me—trying to see how close it could get to answering the test the same way I did. I also asked my girlfriend at the time and my mom to try the same thing.

GPT-4, based only on my tweets, beat them both:

All of this operates on a simple principle: What’s past and present is prologue. How you might feel about a particular situation in the future is going to reliably appear (sometimes in veiled form) in the way you feel about things in the present.ChatGPT and Claude can find subtle patterns, embellish them, and predict how they might evolve in new contexts.

If someone told you the future, would you listen?

Using AI in these contexts to help you refine your predictions about how different decisions will make you feel is a game changer. It can bring you an entirely new perspective on yourself—one that might pull you out of longstanding patterns or can help you see the forest through the trees of your experience.

It picks up on things you know, but couldn’t say. It expands upon what you’ve written so that you can more effectively project yourself into a possible future. It allows you to try on a decision like you would a piece of clothing.

AI can help you turn a decision that was once murky into something that’s clear as crystal. The question is: Will you listen?

The AI's hypothetical and my real journal entries are available for paying subscribers.

Dan Shipper is the cofounder and CEO of Every, where he writes the Chain of Thought column and hosts the podcast How Do You Use ChatGPT? You can follow him on X at @danshipper and on LinkedIn, and Every on X at @every and on LinkedIn.

Find Out What

Comes Next in Tech.

Start your free trial.

New ideas to help you build the future—in your inbox, every day. Trusted by over 75,000 readers.

SubscribeAlready have an account? Sign in

What's included?

-

Unlimited access to our daily essays by Dan Shipper, Evan Armstrong, and a roster of the best tech writers on the internet

-

Full access to an archive of hundreds of in-depth articles

-

-

Priority access and subscriber-only discounts to courses, events, and more

-

Ad-free experience

-

Access to our Discord community

Comments

Don't have an account? Sign up!

Dan, this was really amazing. I kept thinking about Dan Gilbert’s book, “Stumbling on Happiness,” and the research on how bad people are about predicting how we’ll feel in the future. It’s a research book, not an advice book, but he does say that most people overestimate how different they are than everyone else, and that the best (but still not absolutely dependable) strategy is to find others who have faced the same choice and see how they felt afterwards. What you’re doing here takes that even further — to see how a simulated *you* would feel in each situation. Your journal entries are a great foundation for that simulation; I am thinking about what I have that would provide a similar foundation.