GPT-4 Is a Reasoning Engine (2023)

Reason is only as good as the information we give it

September 25, 2024

Sponsored By: Bessemer Venture Partners

This essay is brought to you by Bessemer Venture Partners, a leading venture capital firm investing in artificial intelligence. Discover how AI is transforming industries and creating new entrepreneurial opportunities with their latest free ebook, Everything, Everywhere, All AI. Dive into strategies and real-world case studies that will help you stay ahead of the AI revolution. Ready for the AI era?

Large language models aren’t always right. Their strength—for now—is mimicry and prediction rather than accuracy. But as Dan Shipper writes in this essay from March 2023, these models are only as good as the knowledge they have access to. With OpenAI’s DevDay set for Oct. 1 and Every taking a quarterly Think Week, we thought this was a great time to republish Dan’s essay about AI and reasoning.

Also: We created eight custom wallpapers based on Every’s art for iPhone or Android. Download them for free.—Kate Lee

In 1894, a Boston-based astronomer named Percivel Lowell found intelligent life on Mars.

Looking through a telescope from his private observatory he observed dark straight lines running across the Martian surface. He believed these lines to be evidence of canals built by an advanced but struggling alien civilization trying to tap water from the polar ice caps.

He spent years making intricate drawings of these lines, and his findings captured public imagination at the time. But you’ve never heard of him because he turned out to be dead wrong.

In the 1960s, NASA's Mariner missions captured high-resolution images of Mars, revealing that these "canals" were nothing more than an optical illusion caused by the distribution of craters on the planet's surface. With the low resolution available to his telescope at the time, these craters looked to Lowell like straight lines which, through a chain of reasoning, he theorized to be canals built by intelligent life.

Lowell’s story shows that there are at least two important components to thinking: reasoning and knowledge. Knowledge without reasoning is inert—you can’t do anything with it. But reasoning without knowledge can turn into compelling, confident fabrication.

Interestingly, this dichotomy isn’t limited to human cognition. It’s also a key thing that people fundamentally miss about AI.

Even though our AI models were trained by reading the whole internet, that training mostly enhances their reasoning abilities, not how much they know. And so, the performance of today’s AI models is constrained by their lack of knowledge.

I saw Sam Altman speak at a small Sequoia Capital event in San Francisco earlier in March 2023, and he emphasized this exact point: GPT models are actually reasoning engines, not knowledge databases.

This is crucial to understand because it predicts that advances in the usefulness of AI will come from advances in its ability to access the right knowledge at the right time—not just from advances in its reasoning powers.

AI is here and reshaping every market. Everything, Everywhere, All AI from Bessemer Venture Partners offers deep dives into market analysis and actionable insights for leaders as they navigate the quickly evolving AI economy. Explore how top companies are harnessing AI to drive growth and innovation. This free book also reveals Bessemer's unique operating model, designed to support and back today's top AI-first founders. Ready to craft your winning AI strategy?

Knowledge and reasoning in GPT models

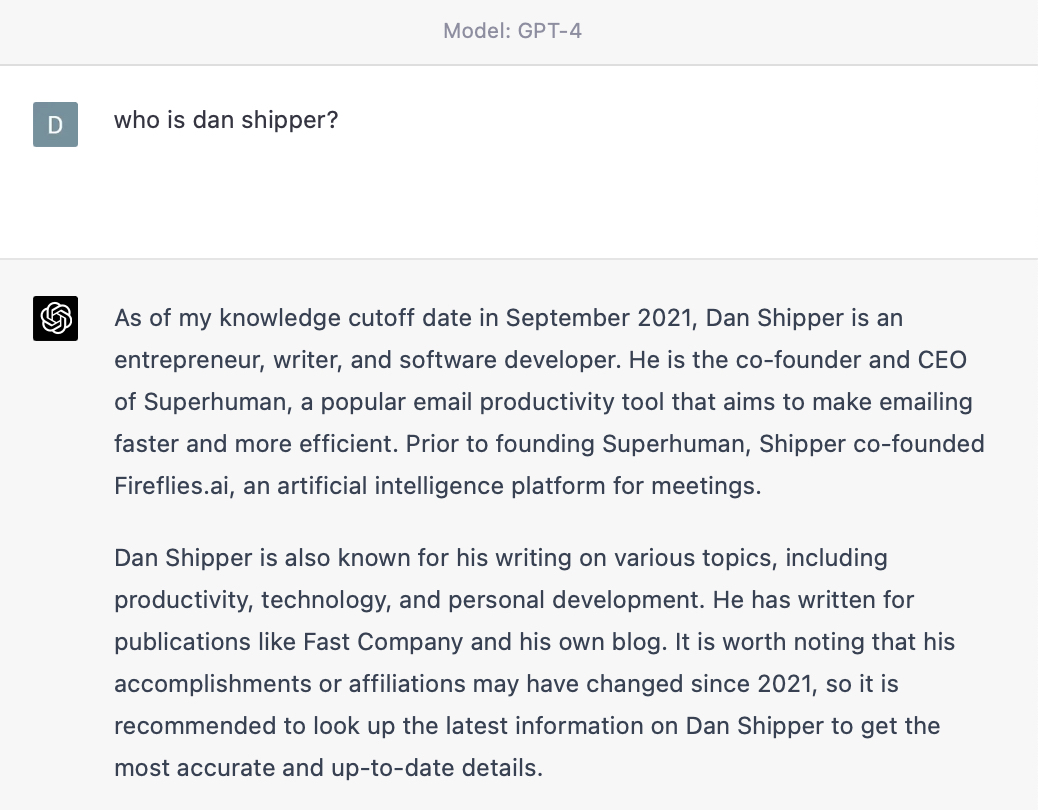

Here’s an example to illustrate this point. GPT-4 is the most advanced model on the market today (note: as of this writing in March 2023). Its reasoning capabilities are so good that it can get a 5 on the AP Bio exam. But if I ask it who I am it says the following:

That’s close to being right except for one big problem…I’m the cofounder of a few companies, but neither of them is Superhuman or Fireflies.AI critics will be quick to say that this proves GPT-4 is nothing more than a stochastic parrot, and that its results should be dismissed offhand. But they’re wrong. Its performance improves dramatically the second it has access to the right information.

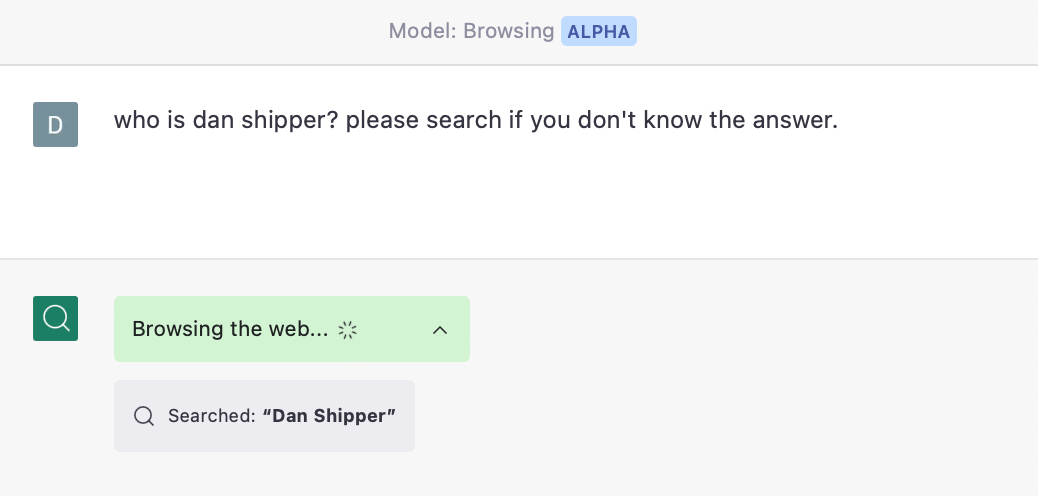

For example, I have access to a version of ChatGPT that can use web searches to ground its answers with what it finds on the internet.

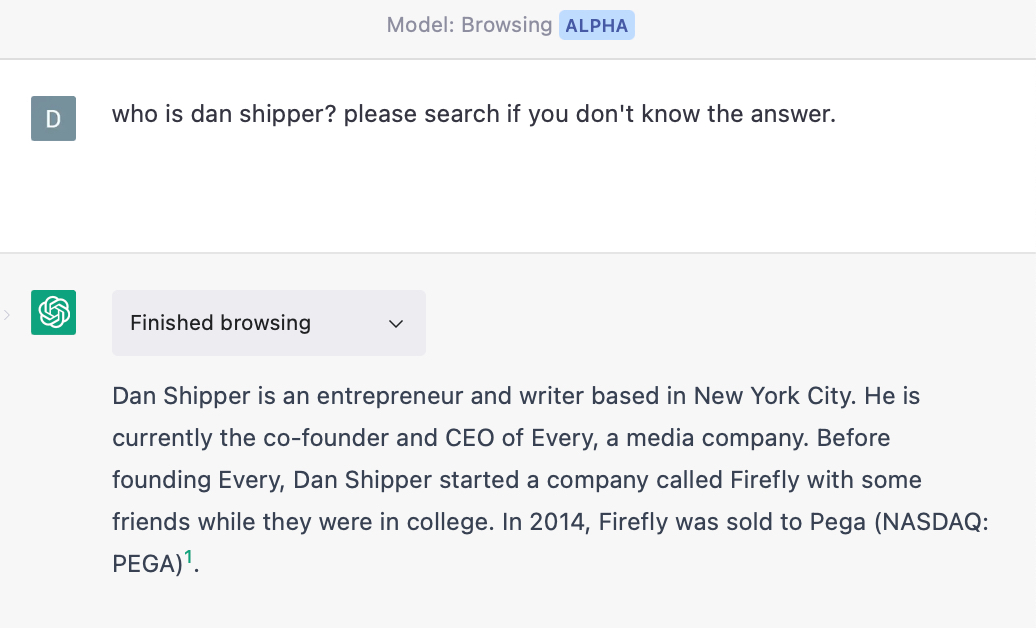

In other words, instead of using its reasoning capabilities to come up with a theoretically plausible answer, it does web research to create a knowledge base for itself. It then analyzes the collected information and distills a more accurate answer:

Now, that’s pretty good! The underlying model is the same, but the answer improves significantly because it has the right information to reason over.What’s going on here? GPT-4’s architecture is not public, but we can make some educated guesses based on previous models that have been released.

When GPT-4 was trained, it was fed a large portion of the available material on the internet. Training transformed that data into a statistical model that is very good at, given a string of words, knowing which words should follow from it—this is called next token prediction.

However, the kind of “knowledge” contained in this statistical model is fuzzy and inexplicit. The model doesn’t have any sort of long-term memory or way to look up the information it has seen—it only remembers what it encountered in its training set in the form of a statistical model.

When it encounters my name it uses this model to make an educated guess about who I am. It draws a conclusion that’s in the ballpark of being right, but is completely wrong in its details because it doesn’t have any explicit way to look up the answer.

But when GPT-4 is hooked up to the internet (or anything that acts like a database) it doesn’t have to rely on its fuzzy statistical understanding. Instead, it can retrieve explicit facts like, “Dan Shipper is the co-founder of Every” and use that to create its answer.

So, what does this mean for the future? I think there are at least two interesting conclusions:

- Knowledge databases are as important to AI progress as foundational models.

- People who organize, store, and catalog their own thinking and reading will have a leg up in an AI-driven world. They can make those resources available to the model and use it to enhance the intelligence and relevance of its responses.

Let’s take these one at a time.

Knowledge databases are surprisingly important

When it comes to knowledge you want to be able to store a lot of it, and you want to be able to find the right piece of knowledge at the right time. In AI this is typically done with a vector database.

Vector databases allow you to easily index and store large amounts of information, and then quickly query for similar pieces of information to give to your model when you need to. They’re so common in AI apps that it’s likely almost every demo you’ve tried over the last few months has included a vector database for some part of their functionality.

In fact, if you want to make an investment that indexes the success of companies building in AI as a whole, one smart move would be to invest in a vector database provider, or a basket of them. (Alternatives might be to invest in OpenAI, or a basket of large cap software companies like Microsoft and Google that build AI, or chipmakers like NVIDIA that build the GPUs that AIs run on.)

Smarter investors than me seem to agree. Pinecone, the most popular vector database, raised funds at a $700 million valuation. Smaller alternatives like Weaviate (which raised $50 million at a $200 million valuation) and Chroma (which raised $18 million at a $75 million valuation) aren’t far behind.

Interestingly, though, most of these vector databases were originally built before the large language model craze. Vectors are incredibly important for all sorts of previous-generation machine learning algorithms like recommendation systems. As a result, the database tooling from providers like Pinecone isn’t purpose built for large language models like ChatGPT.

We’re already seeing newer alternatives springing up that wrap some business logic around the database layer to make it easier for AI developers to do common tasks. Some of these are developer libraries like Langchain and LlamaIndex. And some seem to be more fully featured developer tools like Metal and Baseplate. Just like Pinecone, they are also likely to raise a lot of money, or already have! AI’s advancement is a rain dance that calls forth capital from Patagonia vest-wearing angels.

I find this very exciting because it will make it a lot easier to make AI apps. There’s a tremendous amount of boilerplate code being written to take, say, a PDF or a webpage with interesting information on it, parse it, break it into chunks, store it, and retrieve it for use in AI apps. The more that can happen with just a line or two of code, the better.

When I talk to people about vector databases—even people who have been following AI closely—they typically say, “What’s that?” I think, over time, that will change significantly as we start to understand how important it is for these models to have access to the knowledge that they contain.

Vector databases are how information gets stored and made available to AI applications. One place that I think they’ll get a lot of valuable information from is private, personal knowledge bases.

Private repositories of knowledge are going to be very valuable

People have been saying that data is the new oil for a long time. But I do think, in this case, if you’ve spent a lot of time collecting and curating your own personal set of notes, articles, books, and highlights it’ll be the equivalent of having a topped-off oil drum in your bedroom during an OPEC crisis.

Why? It’s expensive and time consuming to find information that’s relevant to the things you think about. Even if you give AI access to a search engine so it can make queries to find the right information—it’ll cost you money and time.

If, instead, you’ve spent a lifetime gathering and curating information that’s important to you, you can customize your AI experience so it’s more useful to you right off the bat.

Apps like Readwise, Pocket, and Instapaper that allow you to store articles you’ve read (or articles you want to read) are going to be a gold mine to the extent that they hook up to AI tools. They’ll be extra useful because they record the articles you explicitly bookmarked and read, this will make it easier for AI tools to know which pieces of information to weight in their responses.

But the use of personal knowledge databases will get weirder and more advanced than this.

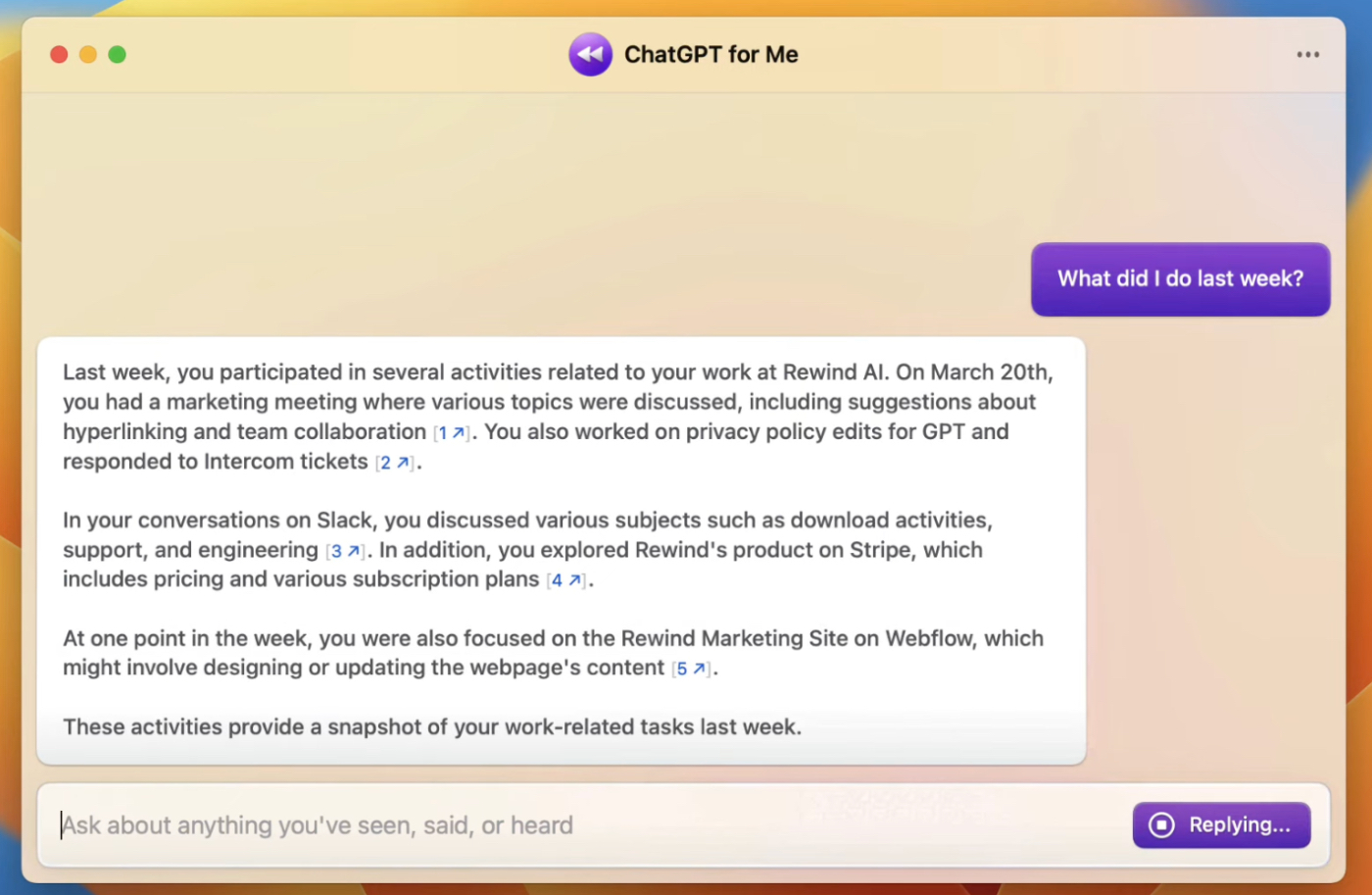

For example, Rewind is a tool that sits on your computer and records everything you see and everything you type. It’s all stored locally for privacy purposes, and you can already hook it up to ChatGPT.

In one of their demos they show a user asking, “What did I do last week?” The AI is able to summarize all of the tasks they did on their computer:

For my part, I’ve installed Rewind, and I’ve been playing around with building little tools to save more of what I encounter online. I made a little app called Tend that sits open on my browser all day, and I can feed it any articles with interesting information for indexing and storage. Later, I’ll build a little ChatGPT plugin to give me access to all the information I saved with it.Wrapping up

When we talk about the future of AI, we tend to focus on its output. Given a prompt, it can think through a complex problem, compose an essay, or create a new scientific breakthrough without much human involvement.

We tend to under-appreciate the significance of the input—what information we feed it to produce those results. Its answers are largely dependent on the information we make available to it for analysis. It’s only as powerful as its starting point.

We don’t pay enough attention to the limits of its knowledge—how much information is locked away, inaccessible to these systems. We also forget how expensive (both in time and in compute) it is to crawl through information sources and find relevant facts. And finally, we underestimate the difficulty of surfacing relevant pieces of information for the model at the right time.

But solving these sorts of problems is just as fundamental as solving for the reasoning capabilities of the underlying models. I’m excited to see what people build.

Dan Shipper is the cofounder and CEO of Every, where he writes the Chain of Thought column and hosts the podcast AI & I. You can follow him on X at @danshipper and on LinkedIn, and Every on X at @every and on LinkedIn.

Find Out What

Comes Next in Tech.

Start your free trial.

New ideas to help you build the future—in your inbox, every day. Trusted by over 75,000 readers.

SubscribeAlready have an account? Sign in

What's included?

-

Unlimited access to our daily essays by Dan Shipper, Evan Armstrong, and a roster of the best tech writers on the internet

-

Full access to an archive of hundreds of in-depth articles

-

-

Priority access and subscriber-only discounts to courses, events, and more

-

Ad-free experience

-

Access to our Discord community

Thanks to our Sponsor: Bessemer Venture Partners

Thanks again to our sponsor Bessemer Venture Partners, investors in the AI economy. Bessemer's new book, Everything, Everywhere, All AI, is packed with market roadmaps and essential insights for leaders navigating the AI landscape. Learn from industry experts on how AI will shape the future. The era of AI is here—are you ready to lead?

Comments

Don't have an account? Sign up!