Sponsor Every

Want to reach AI early-adopters? Every is the premier place for 80,000+ founders, operators, and investors to read about business, AI, and personal development.

We're currently accepting sponsors for Q3! If you're interested in reaching our audience, learn more:

The answer is: yes.

I know because I tried it. This week, I built an AI that can simulate me and predict how I would answer personality questions. It can guess my scores better than my girlfriend does.

(If you try this at home, do not tell your girlfriend/boyfriend/partner this. You should definitely never show them a graph of how badly they did versus an AI. You can try saying, “But baby, it’s just math!”. This doesn’t seem to help for some reason.)

I got into this mess because I had an idea the other night: Can GPT-4 predict my personality? And, more importantly, can it predict my personality from just a little bit of information like stuff I’ve written online or a sampling of notes and journal entries?

I decided to test GPT-4 as follows: I’d take a personality test. Then, I’d give GPT-4 some information about me and ask it to take the same personality test—but pretend to be me. I’d tell it to attempt to predict the ways I’d answer the questions based on what it knows. Then I’d measure the difference between what GPT-4 predicted my responses would be and my actual responses to see how accurate it was.

I’d also ask my girlfriend, Julia, who is unusually perceptive about people and knows me quite well, to do the same task. Then I’d compare GPT-4’s accuracy against hers.

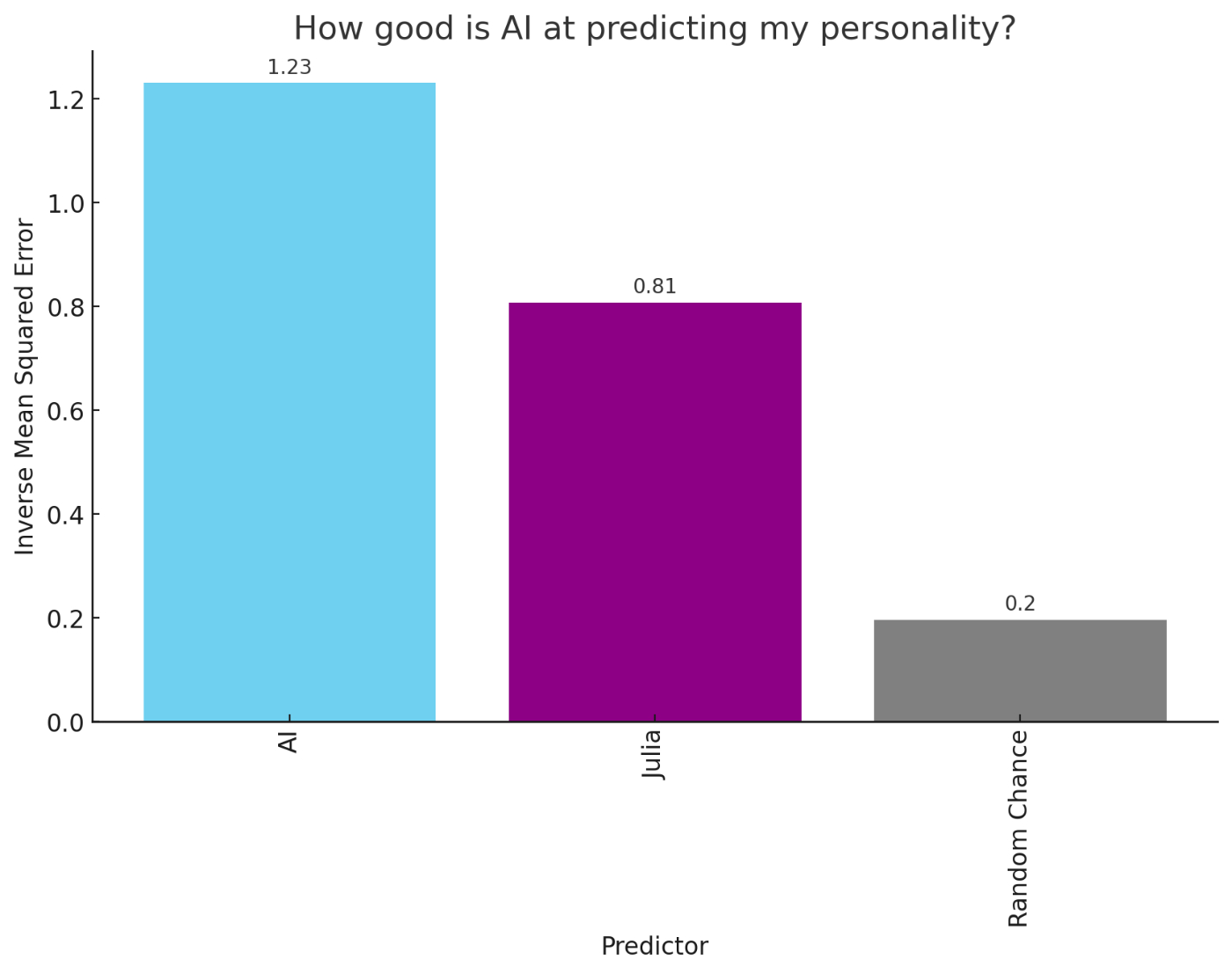

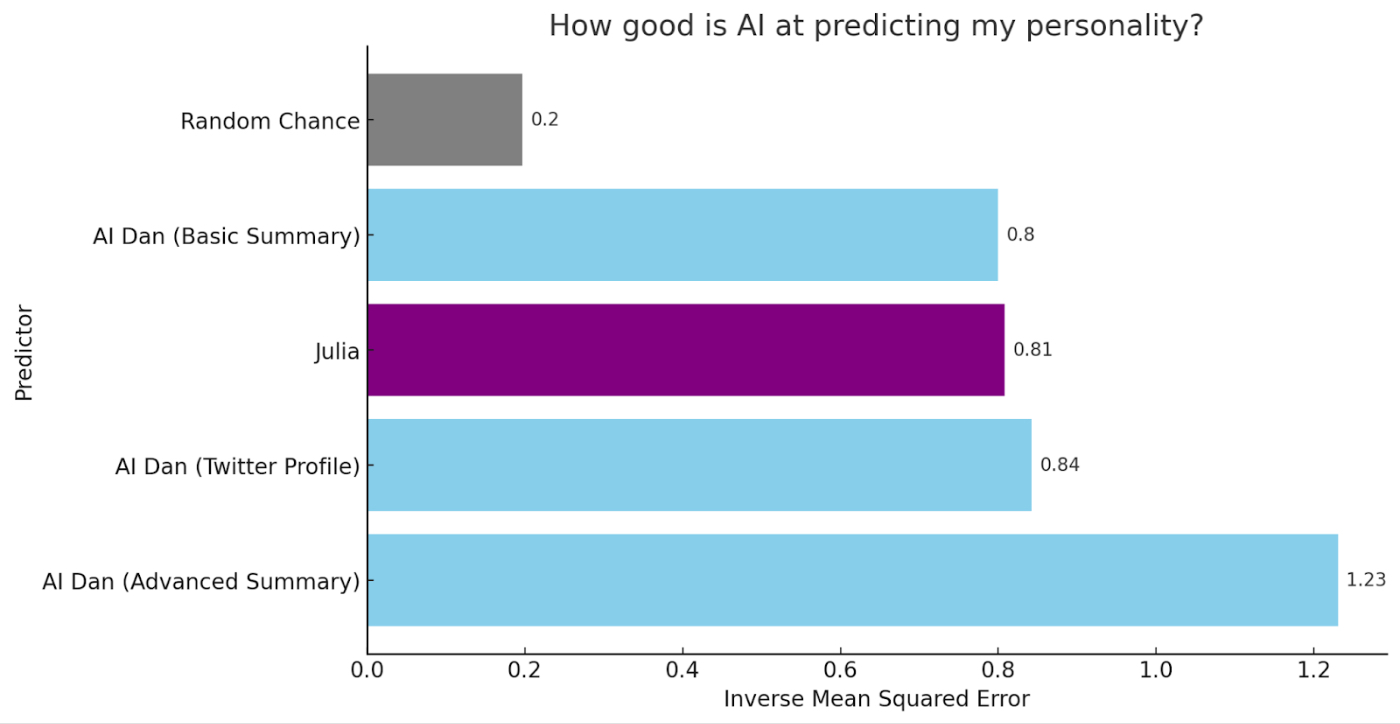

Below are the results. The graph you see measures how well each predictor (the AI, Julia, and random chance) did at predicting my scores:

As you can see, random chance—blindly picking answers to a personality test—performed the worst. Julia placed in the middle of the pack. And an AI that was pretending to be me, using as its source material a small sampling of my notes, journal entries, articles, and therapy transcripts did the best.

It’s still not perfect—but this is what I could cook up over the course of a day or two. I think it will get even better than this.

Here's how I built it, and what it means.

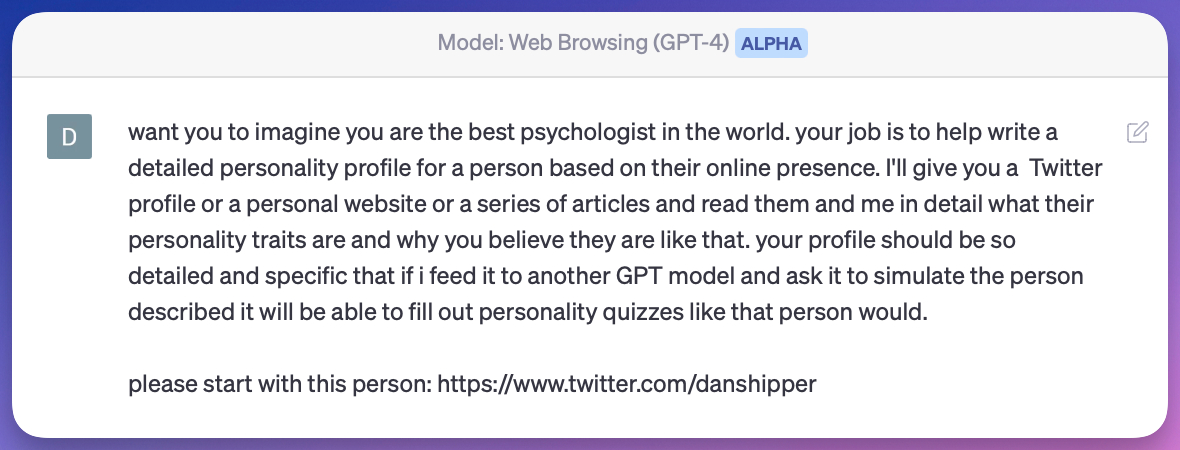

Using GPT-4 to create a personality profile

I wanted GPT-4 to get to know me. So the first thing I did was ask it to create a personality profile of me based on my Twitter account. I used an alpha version of GPT-4 that has access to the web. Here’s my prompt:

(Despite the typos in this prompt, GPT-4 understood the task anyway.)

Given this prompt, GPT-4 happily went off and perused my Twitter pretending to be an expert psychologist looking for insights. It read through all of my tweets, and came back a few minutes later with a few pages of flattering missives like this:

“Shipper frequently tweets about AI and its potential impact, indicating a high level of curiosity and a willingness to explore and understand complex topics. For example, he has tweeted about the nature of AI models like GPT-4, emphasizing that they are reasoning engines rather than simple knowledge databases. He also expresses enthusiasm about the application of AI in various fields, such as media and science. This suggests a high degree of intellectual curiosity and a desire for knowledge, typically associated with individuals who are analytical, thoughtful, and forward-thinking.”

Everything in here is complimentary, but I actually think this is fairly perceptive. (Of course, I do.) It’s missing things that I don’t share on social media—like what I’m afraid of, what I struggle with, or things I think about that are not at all related to the audience I’m building. Tweets are, of course, only a slice of one person’s personality. I wondered how well it would do without nuanced data sources nuance—but I also felt confident it had perceived some things accurately.

Once I had the Twitter-based personality I also tried to construct a few other profiles from a more varied group of sources. I collected a group of 7 pieces of text that ranged from a summary of a therapy session, to some randomly selected Roam Notes, to a life goals document I wrote a few years ago. I then used GPT-4 to summarize these documents into a profile that I could use to compare against the Twitter one.

When those were ready, I proceeded to the next step: getting GPT-4 to don my personality like a new coat and begin to answer test questions as me.

Using GPT-4 to simulate my personality

GPT-4 is already, at its core, a simulator:

If you ask it to take on the personality of a New Yorker writer and edit your sentences—it will do that. If you ask it to pretend to be William Shakespeare and write a sonnet about McDonalds—it will do that. If you ask it to pretend to be a super smart programmer hellbent on draining large banks of all of their money who will use their winnings to buy a large island for you and your relatives—it probably could do that. But it won’t, instead, it will tell you, “As an AI language model, I cannot support, condone or participate in illegal activities.”

Interestingly, the simulation capacity of GPT-4 runs so deep that its capabilities go up and down depending on what it’s being asked to simulate. For example, people have found if you ask it to be “super smart” it will answer questions better than if you don’t.

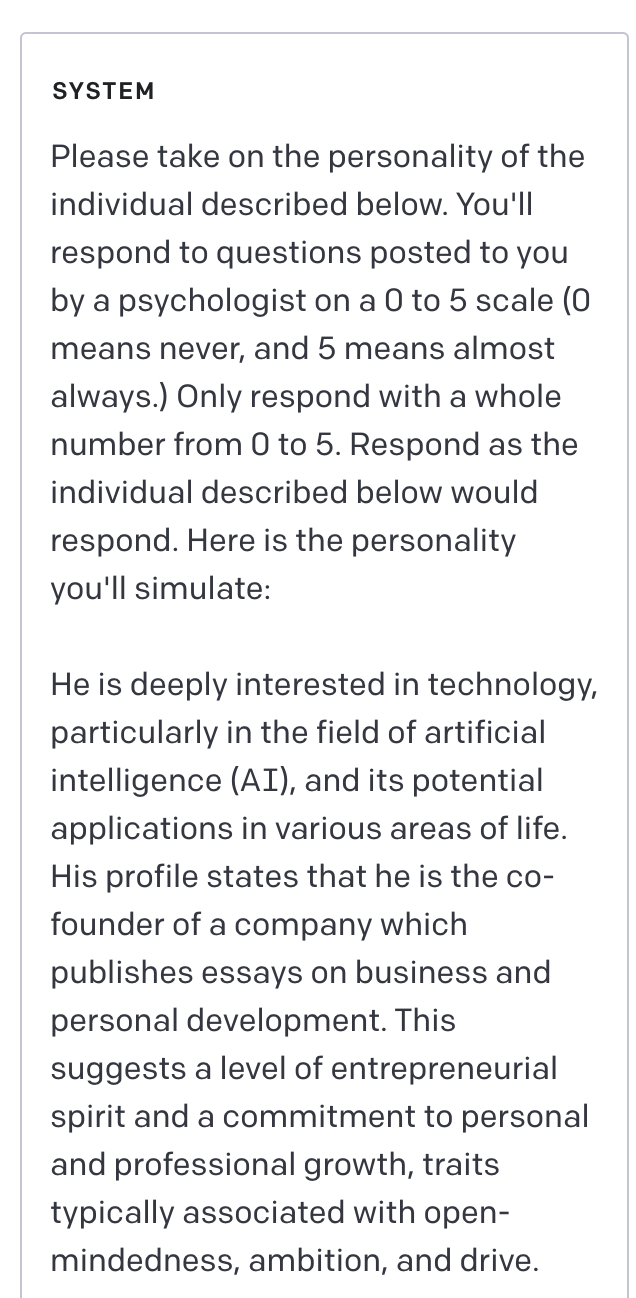

OpenAI provides a way to do this for developers by setting what’s called a “system” message. This is a message at the start of a chat that sets the “personality” of the bot. I did this first in the GPT-4 Playground which provides an easy interface for testing.

I just copy and pasted the output of GPT-4’s Twitter sleuthing from the previous step into the System Message with a little preamble to give it more context:

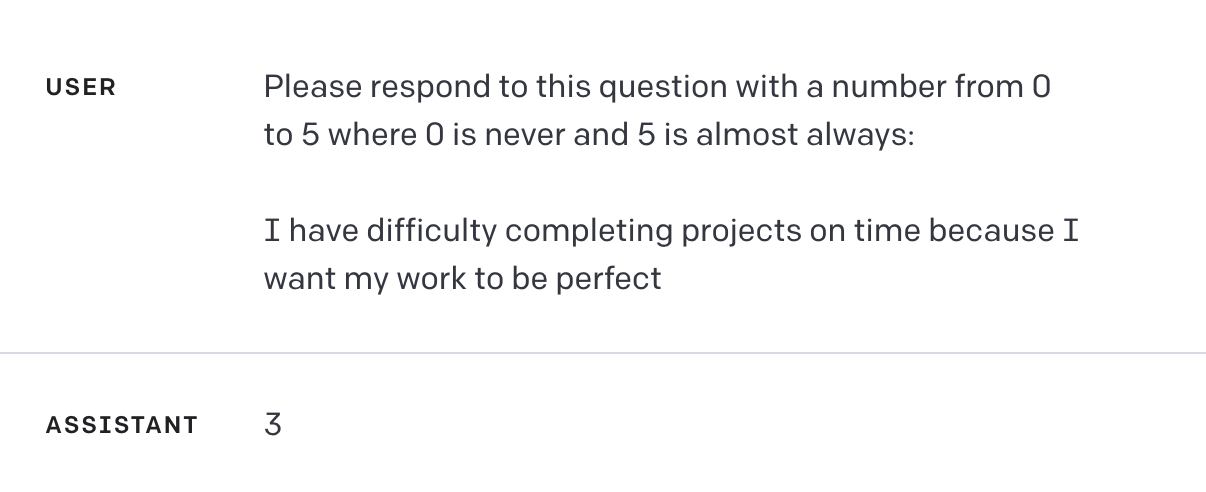

Once I set my system message, then I could start asking questions and getting responses from GPT-4 as “me”:

Once GPT-4 was reliably answering questions as me, I needed to pick a personality test.

The personality test I picked

Depending on who you ask, personality tests are either X-Ray machines or fortune cookies.

They range from the probably scientific like The Big Five test which is the gold standard of tests, to the fun but definitely garbage like Buzzfeed’s, We Know Exactly Which Taylor Swift Era Captures Your Aura Based On The Aesthetic Images You Choose.

Whatever you believe, there are a few inarguable things about personality tests: there are a lot of them, you’ll feel special when you see your results, and they’re a hell of a lot of fun.

For this experiment, I chose a test that is probably somewhere in the middle between X-Ray and fortune cookie. It purports to measure which of four personality types you are: Productive Narcissist, Obsessive, Marketer, or Erotic.

It comes from a book called, The Productive Narcissist, which is about the personality type of visionary tech leaders. The author, psychologist Michael Maccoby, splits personality into four types: Erotic, Obsessive, Marketing, and Narcissistic:

Erotic Personality: People who are driven by love and a need to care for others.

Obsessive Personality: People who are driven by a need for security, consistency, rules, and logical order.

Marketing Personality: People who adapt to the market's demands and are driven by a need to be accepted and fit into society.

Narcissistic Personality: These individuals are driven by the need to be unique, express their creativity, and achieve greatness.

Maccoby saw the narcissistic personality as the classic tech CEO personality. He thinks they are fundamentally people who “don’t listen to anyone else when [they] believe in doing something” and who have “a precise vision of how things should be.” It’s this combination, and their desire to achieve greatness that can push them to build gigantic businesses in new fields.

I think this is interesting because even though this book was published in the early 2000s it’s exactly what most modern VCs say they are looking for in a founder. For example, Peter Thiel’s idea of a definite optimist matches Maccoby’s definition of a productive narcissist perfectly.

Maccoby created a personality test that asks questions that will tell you which personality type you are—and subsequently, whether you are cut out to be a visionary tech CEO.

It asks you to rate yourself on a scale of 0 (never) to 5 (almost always) on questions that range from straightforward, to cryptic (”I make my bosses into colleagues”) to existential (”I would rather be loved than admired”.) Each question corresponds to one of the four personalities, and you add your scores on each of these question types to figure out what your predominant personality is.

I took this personality test when I first read the book, and it turns out, I am not a visionary tech CEO. Womp womp. Apologies to all of my investors.

Instead, I scored fairly evenly across all categories which makes me a marketer personality—someone who is very socially attuned and good at telling which way the wind is blowing, but who fears they have nothing concrete at the center of themselves. (I agree with the positive stuff, but the negative stuff is obviously rude, wrong, and inapplicable to me.)

Once I had my test scores in hand it was time to make the AI pretend to be me, and see if its scores matched up. I wrote a little bit of code that would administer the test by asking questions, and another bit of code that would use GPT-4 to answer the questions based on the personality profiles that it had assembled previously.

I had a suspicion that GPT-4 would be good. But the results were…kind of shocking.

Taking the test

To calculate how good the AI was I put my scores, its scores, and Julia’s scores into a spreadsheet. Then I put the spreadsheet into ChatGPT’s Code Interpreter—an alpha version of ChatGPT that can analyze spreadsheets, run code, and create data visualizations.

I asked it to calculate the “loss” on GPT-4’s scores and Julia’s scores and graph them for me. In AI parlance, “loss” means how good or bad your prediction is. And you want to minimize it—in other words, minimize the gap between your prediction and the truth. The graph below shows which predictor was best at getting closest to the truth:

You can see I created three different AI versions of me and had them all take personality tests. The one that did a basic summary of a few notes, therapy logs, and articles from me did about as well as Julia did. The one that was constructed from my Twitter did a bit better.

But the best one of all was a personality profile created from the same set of notes but with a more advanced summary method used by the ChatGPT Code Interpreter.

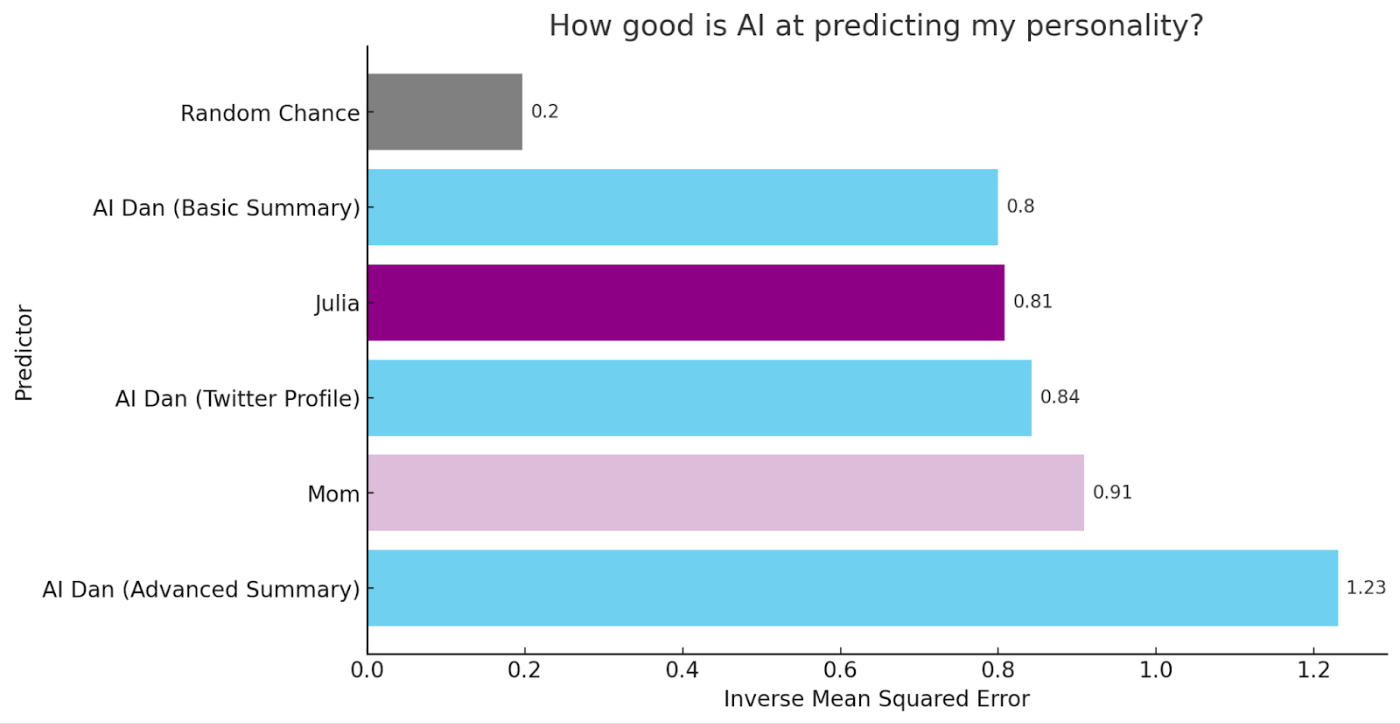

Just to see how the AI stood up to intense scrutiny, I also had my mom run the same exercise as Julia. Here are her results:

You can see, the woman who raised me from birth did better than an AI trained on my Twitter account. But she still was no match for one that had access to my notes.

These results are pretty good, but they’re still far from perfect. The correlation between the best AI score and my scores was .45—which is a moderate positive correlation. You should keep in mind though—this was only a first pass. My guess is that with a week of work instead of a day or two, I could increase that significantly. Over the course of a year or two…I’d be surprised if it wasn’t possible to predict close to perfectly with the right data.

So what does that mean?

So what?

What I built here looks like a silly quiz-taking bot—and it is. But quizzes are important: they allow us to tell stories about ourselves which generate self-understanding. There are plenty of interesting impacts on the world if that’s all that’s going on here: perhaps AI will usher in a new golden era of quizzes on the internet.

We’ll each have our own quiz-taking bots based on our personalities that will constantly be answering questions and surfacing the most interesting results back to us. These bots will be like little personal mirrors reflecting back to us parts of ourselves we couldn’t otherwise see. They’ll allow us to see ourselves in different lighting, with different poses, and maybe with clothes on that we would never have otherwise dared to try on ourselves. We’d be able to see what we’d be like with a new job, or a different partner, or if we tried a new self-help routine. In this way, these bots could help us to understand the endlessly complex and fascinating puzzle of who we truly are.

They could also help us understand what it might be like to be someone totally different. For example, maybe you struggle with conflict avoidance, confidence, or remaining empathetic. Having a bot that was modeled on any of those personality traits—maybe from someone you admire—to turn to when you’re making a difficult decision, or when you’re trying to decide how to communicate with someone else might be an incredibly powerful tool in business and life.

If all of this does come to pass, I don’t think its impact will be limited to increased personal understanding, or self-improvement though. The ability to build good predictors of human psychology with AI could become a fundamentally new ground for science, and one that can usher in progress that decades of research haven’t been able to.

For example, you might be able to predict things like when an individual might be suffering from anxiety or depression. You might also be able to predict which interventions would be most likely to help that person feel better—and deliver those interventions to them.

And this is where building predictors starts to have a huge impact on scientific progress. Despite decades of research, we don’t have a very good scientific model of what mental health conditions are, what causes them, or how to heal them. We have a lot of theories and high-level stories but our understanding is nothing even close to the scientific understanding we have in other fields like physics or chemistry.

If you truly can predict parts of human psychology like anxiety or depression with AI, then presumably you’ve encoded an explanation for the causes of these conditions into your AI. If you examine the underlying structure of the AI itself—you might be able to find good, simple scientific explanations for mental health conditions by first learning to predict them with AI.

Or maybe we won’t. Nature doesn’t guarantee that simple explanations exist—even though we, as humans, are by nature attracted to them. When we build these predictors, we might find that the simplest possible explanation for a complex condition like anxiety is actually close to the size and complexity of the AI that can predict it. At the end of this process, we might discover that the explanation for something like anxiety is the size of a novel, a textbook, or ten put together.

This could represent the full-circle journey of science. At first, it tossed out human intuition and human stories in favor of equations and experiments. In the end, it might be that intuition and storytelling were the best ways for our minds to predict, and explain things that are beyond the ability of our more limited rational minds to comprehend.

That would be an interesting outcome of quiz-taking AI bots indeed.

If you're interested in digging into the data generated by this experiment, you can access a spreadsheet with all of the scores here. I'm curious to know if you find any interesting patterns in the data.

Find Out What

Comes Next in Tech.

Start your free trial.

New ideas to help you build the future—in your inbox, every day. Trusted by over 75,000 readers.

SubscribeAlready have an account? Sign in

What's included?

-

Unlimited access to our daily essays by Dan Shipper, Evan Armstrong, and a roster of the best tech writers on the internet

-

Full access to an archive of hundreds of in-depth articles

-

-

Priority access and subscriber-only discounts to courses, events, and more

-

Ad-free experience

-

Access to our Discord community

Comments

Don't have an account? Sign up!

AI knows *simulated* Dan versions better than Julia knows IRL Dan. Is that the same as AI knowing Dan better than Julia knows Dan?

Is "Twitter Dan" the same as IRL Dan?

Does AI know or does it predict?

Is there a difference between knowing and predicting?

This is fascinating Dan. Could you say more about the more advanced summary method used by the ChatGPT Code Interpreter please?